In Search of Lost Empire

The Struggle for the Sahel

“Where the ultimate decision concerning the safety of one’s country is to be taken, no consideration of what is just or unjust, merciful or cruel, praiseworthy or shameful, should be permitted; on the contrary, putting aside every other reservation, one should follow in its entirety the policy that saves its life and preserves its liberty.” - Machiavelli [Discourses, III.41]

Introduction: Watching the Sahel Slip Away

With little fanfare, France has withdrawn its troops from Mali and announced it will pull them out of Burkina Faso, following a decade-long counter-terror operation in Africa’s Sahel region. For now, the troops are being moved to Niger, which still has a pro-French government. Despite historic reluctance to relinquish their economic and political interests and say goodbye to the ghost of their empire, the French seem to have accepted that the game is all but over for them in Africa. However, even so, they can’t admit that after over a century of looting both openly and through supposedly benevolent economic suzerainty. Regardless, they don’t themselves have the determination nor the necessary goodwill of their former subjects to maintain their imperial position and help the states fight a war on terror. Instead, they have to lay the blame at the foot of another power, of course, Russia. Military juntas have given France the boot, and as in much of Africa, Russia is seen by many as a fairer partner without a colonial past on the continent- the same perception the West fought against the entire Cold War. Much is being made of Russia’s growing influence in this blighted region by the usual scribblers. Most of all, many sources are promoting allegations that the Wagner Group private military contractor, currently famous for its oversized role fighting for Russia in Ukraine, has been employed by governments in the region to support- or lead- the fight against jihadists who now control a large amount of territory. The Western policy class, at least, does not want to go down without a fight. It is a hard pill for them to swallow that if these countries are truly sovereign it is for them to handle their own security concerns- even if that means aligning with Russia and hiring Wagner. Hand-wringing notwithstanding, that appears to be the direction they are going.

Background: Fleecing the Land of Sand and Gold

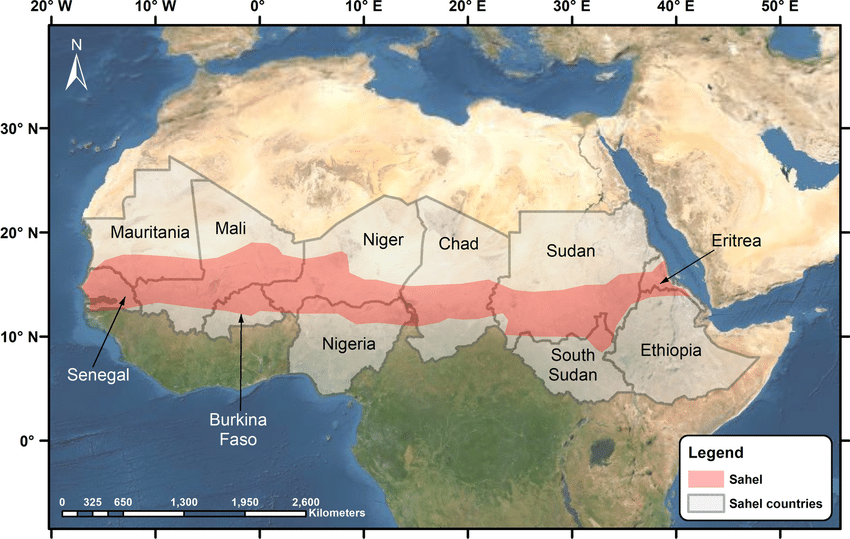

The Sahel is a narrow band of semi-arid land separating the Sahara Desert and the savanna. It was once the geographic center of France’s enormous African empire. Many of what are known as the Sahel states are primarily made up of the Sahara, however as the Sahara is largely uninhabitable, their populations are concentrated in their more temperate southern regions. In America, the Sahel is mostly known by environmentalists who are interested in the fight against the expansion of the Sahara- desertification- which has taken shape as a project known as The Great Green Wall. As I explained in my article about the Dutch farmer protests, I am confident this relates to local conditions, and not “global climate change.” I read an article about this in New York Times Magazine when I was a young man in the mid-2000’s, and it said Western “experts” were teaching them to plow around trees instead of cut them down. I distinctly remember thinking it was surely white people who taught them to cut down the trees in the first place, as it is self-evident that removing what trees you have at the edge of the desert- instead of harvesting branches- is a bad idea. This is a sort of microcosm of all of their problems. In seemingly every way, the Sahel is only getting hotter- and if its problems cannot be fixed it may become hell.

Despite the challenging climate, the Sahel was once the center of some of Africa’s greatest native empires, most notably the Malian Empire of the famous king Mansa Musa. With large gold deposits and other mineral wealth, as well as the once-legendary city of Timbuktu controlling the Niger River Basin-Mediterannean trade, it became a tempting target for curious and avaricious Europeans hell-bent on dividing up the world. Despite, or perhaps because of, the mineral wealth, the region is now impoverished and unstable, and and the states are seriously challenged by the explosive growth of radical Islam in the region.

The French are like the Canadians in that in the “Western” world they have a reputation as being bastions of a kind and benign progressivism, but in reality they brutally exploit the resources of the “Third World.” While France reluctantly let go of its African Empire in the de-colonization era following the Second World War, a great amount of damage had already been done from nearly a century of Colonial rule. Following independence, the French owned much of the economy of the region. Further, there was the usual post-colonial political meddling, with some going as far as to claim France has assassinated 22 African leaders since independence [without researching them one by one, the logical conclusion is that France had a direct or indirect role in the death of some, but not all, of these leaders; they were undeniably involved in the events leading to Libyan leader Gaddafi’s death.] France has not been shy about the open and direct use of its military either, “intervening” in Africa more than 50 times since 1960. Nathaniel Powell, writing for The Conversation, published an article titled “The Flawed Logic Behind French Military Interventions in Africa.” He describes France’s diverse goals in the region as follows:

“The main reason boils down to France’s principal foreign policy priority in Africa since 1960: maintaining stable African political orders broadly favourable to French interests. These interests are diverse and change over time. They include the prestige associated with influence and power projection in another continent, as well as the maintenance of a constellation of states supportive of French diplomacy. The promotion of French language and culture, business interests and investment opportunities are also important, as well as concerns over immigration, and more recently, the “war against terrorism”.”

In terms of post-colonial economic control, the most notable feature is that France continued the system of the colonial CFA Franc created in the 1940s [technically it is two currencies, there is an Western and Central CFA Franc; the countries in this article are all in the Western zone.] The basic system was that the countries must deposit half or more of their foreign reserves in the French Central Bank in exchange for their currency being pegged to the Euro at a fixed rate. There are some advantages to this, most notably that it prevents irresponsible governments from causing Zimbabwe-style hyper-inflation. At the same time, a country can never be truly independent when a foreign power controls its currency policy without its input. This is inherently a paternalistic legacy of colonialism; this is the national equivalent of your father managing your retirement account. It is also somewhat strange that a region where the top export is gold should be storing foreign reserves in this fashion when they could simply store gold in vaults spread among multiple countries. The CFA Franc system gained notice recently when a 2019 video of Giorgia Meloni, now Italy’s Prime Minister, re-surfaced where she accused France’s rapine of causing the immigration crisis, claiming half of Burkina Faso’s gold mining revenue went to the French State.

Meloni’s argument brings up a key factor in how wealthy countries treat poor countries: in America I have described this as our two policy options being “invade the world, invite the world” or “Fortress America.” In short, wealthy countries destabilize and exploit countries, and then are flooded with immigrants from those countries, such as described in my article about Haiti. The other option is to close your country to migrants but also leave other countries alone. Neither of these are great policies, they are just sadly the only two which ever seem to gain political currency in the West.

There were a variety of factual problem’s with Meloni’s statement, as outlined in this BBC article, which functions as fact-based apologism for neo-Colonialism. It is indeed the country’s reserves which are stored there, not their trade profits as such, and they do receive interest, though surely at a lower rate than the French State loans out the money. In short, it’s a system they can sell as fair that anyone with healthy skepticism knows wouldn’t exist if it wasn’t exploitative. However, as the BBC explains, in 2019 France removed the 50% reserve requirement for the Western zone, and in 2022 it began transferring back reserves. This is a major move towards genuine independence for these countries, preceding the military withdrawal we are now seeing.

Trouble Blows in with the Desert Winds

In the 2000’s, the Sahel “only” had problems similar to the other post-Colonial regions of Africa. This changed when European countries- with France one of the most enthusiastic participants- decided it was time to overthrow the ever-troublesome Libyan strongman Gaddafi [I gave background on some explanations for this in my article about NATO strategy.] Though for Western powers Gaddafi was an uniquely destabilizing figure- a staunch anti-colonialist who challenged the very notion of the modern nation state- in other ways Libya was a beacon of stability in Africa, growing wealthy under his iron-fisted rule. The decision to overthrow Gaddafi- in hindsight an objectively bad one- destabilized the entire broader Mediterranean world, which the Sahel has been on the periphery of through trade since antiquity. In this instance, Gaddafi had a sort of Varangian Guard made up of men from a nomadic Saharan tribe known as Tuaregs. Following the fall of the regime they fled Libya to their home regions, primarily in Mali and Niger, possessing large quantities of weaponry looted from Libya’s enormous armory.

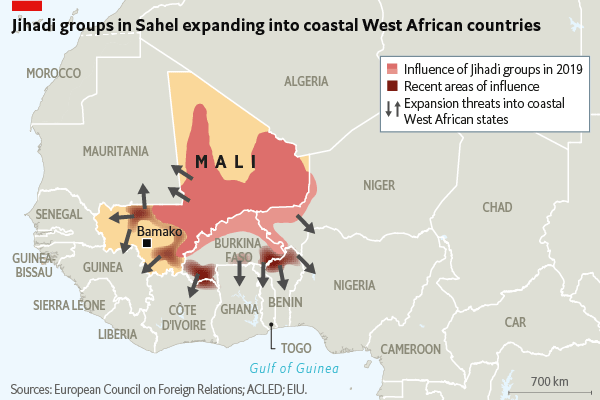

After returning home, Tuareg soldiers joined with militant groups in the already lawless Sahara, further destabilizing the region and seriously challenging the authority of the state. At the same time, the US government was involved in trafficking Libyan arms into Syria to support the jihadists they were using try and overthrow the Syrian government. The ultimate result was the empowering of Al Qaeda and the rise of the Islamic State. The disease of radical Islamic terrorism- already a major problem- spread rapidly across the Islamic world, finding adherents among the most marginalized people in this most marginalized region. The three main terrorist factions in the area are a coalition of Al Qaeda affiliates known as Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb, The Islamic State in the Greater Sahara, and a home-grown extremist group Ansaroul Islam, founded by a Burkinabe preacher named Ibraham Dicko, who was replaced by his brother Jafar Dicko upon his death [apparently the name Dicko is like Smith over there, I’ve ran into it several times while researching this article.] On top of this, northern Nigeria’s notorious Boko Haram terrorist group, best known for kidnapping schoolgirls, has a heavy presence to the southeast.

Though sparsely populated, the southern Sahara is home to a variety of tribes with different lifestyles who are in competition for the areas which feature precious water. The photographer Pascal Maitre described what happened when the Tuareg soldiers and then jihadists arrived in the region, “The once delicate balance between Fulani herdsmen, Dogon and Bambara farmers, and Bozo fishermen has been upset.” Four different tribes with three different modes of subsistence were managing to live together- and then their lives were confronted with terrorism. The Fulani, one of the largest tribal groups in the area, joined militants in especially large numbers. Though local groups differed, this was replicated all over the region, creating a conflagration of violence, displacement, and radical Islam.

The “African-Led” Frenchman’s Burden

As the world’s eyes were on North Africa and the Middle East, it seemed everyone had forgotten about the Sahel. Everyone that is, except, the French. As if by habit, in 2010 the French intervened in the Cote d’Ivoire after a President refused to leave office following losing an election. The Atlantic called it a “model of a successful intervention.” Backing a political faction widely seen as having legitimacy is one thing, but terrorism, like hell, is not easily conquered.

Following a 2012 coup, Tuareg Rebels and and Islamic terrorist groups took control of around half of Mali. The French entered Mali after the passing of a UN Security Council Resolution and at the request of the interim government on January 11, 2013, in what was called Operation Serval, after a common desert wild cat. The French-led “coalition” of themselves and Sahel nations took the name “African-Led International Support Mission to Mali,” or AFISMA, following the noble tradition of governments creating names which are the exact opposite of the truth. This operation was supported by most European countries, including every colonial power besides Italy to ever control land in Africa. AFISMA operated under the auspices of the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali, or MINUSMA, reaching the point of satire for governments using ridiculous and euphemistic names [the acronym is for the French name, which has a different word order.] In 2014, on the first anniversary of the operation, France 24 published a timeline which was a sort of ill-advised “victory lap” [though nowhere near as bad as George W. Bush’s “Mission Accomplished.”] They wrote:

“Twelve months on, French troops have been praised for successfully pushing back and diminishing armed groups like al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar Dine and the Movement for Unity and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO). But sporadic unrest in Mali’s troubled desert north continues.

Mali has elected a new president and is enjoying relative stability, but 2,500 French soldiers still remain on the ground. Reduced by about half since the height of the military operation, French forces should now be shaved down to 1,000 soldiers in the coming months.”

It is true that, as these operations usually go, the arrival of new sophisticated weaponry and well-trained troops caused the rebels and jihadists to retreat and change their tactics. Basically, the jihadists didn’t stick around in the cities to fall victim to French airstrikes, against which they had no defensive weapons. Instead, they headed for the hills, or in this case, the sand dunes.

The problem for the French is that such irregular forces are always capable at “living off the land,” and their members generally come from severely impoverished backgrounds so that camping in the desert is not so different from life at home. Unfortunately, to militants, “living off the land” means attacking and raiding the impoverished people who live there, commonly driving them to the cities as internally displaced persons. Though relatively less poor than rural areas, the cities in this region are also not in a financial position to absorb a lot of refugees into their homes and economy. The French did, at least, manage to oversee an election, so Mali again joined the “democratic nations,” but that did not solve any of its problems.

France followed Operation Serval with Operation Barkhane, named after a type of dune common in the Sahara. This mission combined Operation Serval with Operation Epervier, a decades long military mission in neighboring Chad, and spread to other nations in the region including Burkina Faso. To France’s credit, this mission had a somewhat more broad coalition, bringing in military heavyweights such as Estonia, and supported by a smaller, but diverse group of nations: the United States, the United Kingdom, Canada, and Denmark. This operation did not go nearly so well for France, most likely due to the lack of snappy acronyms.

In reality, Operation Barkhane suffered from the problems common to such efforts, namely, a paternalistic imperialist attitude, a failure to win “hearts and minds,” and the difficulty in distinguishing terrorists and their supporters from the general population. In one particularly egregious instance, France mistook a wedding in Mali for a terrorist gathering and killed at least 19 civilians with an airstrike. These sorts of mistakes are inherent to warfare, but they are particularly hard to swallow when coming from a former imperial overlord who ruled your country within living memory. The situation in the Sahel continually deteriorated throughout the course of Barkhane. The Harvard International Review published a post-mortem of the military operation on January 30, 2023, it explains,

“Last year, there were 4,839 casualties due to such extremist violence in the Sahel, a 70 percent increase from the previous year. This jump marks the sixth consecutive year of rising rates of violence. These jihadists have taken advantage of popular resentment towards corrupt leaders, widespread poverty, and and one of the world’s fastest growing populations to gain power.

On top of this, counterinsurgency is notoriously difficult to execute. Counterinsurgency soldiers must engage in traditional combat, while, arguably more importantly, becoming part of society in order to sway citizens away from insurgents. This is a formidable goal, particularly for former colonial powers, like the French, who have had significant trouble influencing Malian citizens. Further complicating the situation is the fact that counterinsurgency is associated with high rates of violence against civilians.”

The wars also had a high cost to the French for no obvious return on investment. According to the Spanish publication Atalyar, France spent 2 billion Euros on Barkhane, not counting civilian or permanent base maintenance costs. As a percentage of French military spending this is quite small, but it is still a lot of money for a quagmire that is going nowhere. In the same article author Alvaro Escalonilla writes, “The lack of concrete progress in the fight against terrorism has caused Mali to become for France a desert version of Vietnam or Afghanistan for the United States.” Further, they lost 13 soldiers in a helicopter accident in Mali 2019, which, again, by the standards of warfare is few, but for something serving no good purpose is too many. France claims it sees itself as having turned the tide against jihadists but being unable to win, and it has left governments that will struggle stand on their own. It also cut anti-poverty foreign aid that millions of Malians rely on, which is sure to make things all the more volatile. The situation is kind of ironic, because with France’s large African population their actions in the Sahel, with mistakes like bombing the wedding party, are probably more likely to generate homegrown terrorism than terrorists in the Sahel are to threaten France. Unlike terror groups in the Middle East, terrorists in this region have not shown a proclivity for launching complex attacks abroad and function more as particularly brutal local militias or gangs.

Either way, France’s unsuccessful war on terror overstayed its welcome in key countries, and in their defense, when asked to leave, they looked at the ruins of their efforts and did so. An end of democracy and perhaps an end of French influence.

Coups in the Time of Covid

In The Conversation article cited above, published May 30th, 2020, Nathaniel Powell proved both timely and prescient, writing,

“Ongoing French and international efforts in support of Sahelian states against jihadist and other armed groups risk strengthening precisely those leaders, regime elites and security forces whose actions helped generate the very crises France seeks to resolve.”

As if on schedule, while the world was in the throes of covid-mania, the Sahel was rocked by coups, beginning with a coup in Mali in August of 2020. According to Wikipedia, Fancophone West Africa has had 9 coups or coup attempts since 2020, not counting the fact that the current leader of Chad illegally took power following his father’s death [which the West accepted due to French support] and himself claims to have faced a coup attempt. Mali actually had a second coup in May of 2021, led by Assimi Goita, the leader of the first coup, replacing the government he put in power. This was quickly followed by a September coup in Guinea against a President described as increasingly “messianic.” The Guinea coup was led by Special Forces commander Colonel Doumbouya, who made the strange and creepy statement, “we don't need to rape Guinea anymore, we just need to make love to her.”

In 2022, Burkina Faso followed Mali in having two coups within a year. In January, the military deposed the President Roch Kabore “without violence,” citing deteriorating security. That September, that coup’s interim President Paul-Henri Damiba was overthrown and an army captain named Ibrahim Traore took power.

The junta governments have decided to manage their own security concerns. At the end of January 2022 Mali expelled the French Ambassador, Joel Meyer, shortly after demanding Danish “peacekeepers” leave the country. This was in response to French Foreign Minister Jean-Yves Le Drian saying the government had taken, “illegitimate and takes irresponsible measures.” This was greeted by widespread celebration, demonstrating just how unpopular France is in the region. It leaves you wondering what the Foreign Minister thought was going to happen, saying that of the government of a country where his government currently has troops. In mid-February the Malian government told France to remove its troops “without delay.” Macron agreed to do so and the troops had been re-located to Niger by the end of the summer. The website LibyanExpress, clearly hostile to France, claims that French commentators are blaming this on an inability to “co-habitate” with Wagner mercenaries; I have not been able to independently verify this, but if France’s media class is anything like America’s, that is certainly what they would say, despite that France was outright told to leave.

At the beginning of 2023 Burkina Faso followed suit, telling the French to leave. France again agreed, and withdrew its ambassador, though it said this was not punitive so much as to meet in Paris and decide a path forward. There was again widespread rejoicing at the expulsion of French troops, though according to people interviewed by The Daily Mail there were mixed opinions about if Burkina Faso should move closer to Russia. For all of this, the government of Burkina Faso denied a diplomatic break with Paris, as well as the presence of Wagner mercenaries in the country.

All of this is a large blow to France’s long time effort to democratize, or at least stabilize, the region, which had shed it’s reputation as Africa’s “Coup Belt.” Francophone West Africa has certainly regained that reputation, with an outright majority of the worlds coups and coup attempts in the last 3 years having taken place in the region. The junta governments seem to be looking to each other as a source of support and stability. The Foreign Ministers of Guinea [which has had bad relations with France for some time,] Mali, and Burkina Faso met on February 10, 2023 to discuss the possibility of forming an economic union between the states. Reuters reports:

“The Bamako-Conakry-Ouagadougou link will be a basis for fuel and electricity exchanges, transport links, cooperation on mineral resource extraction, rural development and trade, the statement said.

It will mobilise resources for a railway network linking the three capitals and centralise the fight against insecurity, it said, adding that Burkina Faso's interim President Ibrahim Traore had asked his government to enact the plan.”

It’s incredible that in 2023 these neighboring countries don’t have rail-linked capitols, and it speaks very poorly of French direct rule followed by French suzerainty. Creating that rail through an impoverished violent area is easier said than done, but it represents looking to African solutions [though it seems most likely a Russian or Chinese firm would build the rail.] Still, rail is just an idea for the future. For the time being, the the coup governments have seem to have been unable to improve security; the antiwar.com country page for Burkina Faso is mostly just a list of brutal terrorist attacks. If the allegations that they have hired Wagner to help them are true, it seems as if it is yet to work.

An Army of the Night

With near unanimous consensus, the Western commentary class is condemning the Russian Wagner private military contractor for its role in Africa. Look at a Google search for “Wagner Africa.” I’ll get to the hypocrisy and silliness of this shortly, but they are all quite sure Wagner is destabilizing Africa. The problem is they don’t appear to be basing that on anything. Not the part about having a destabilizing impact: there is no proof that Wagner is in most of these African countries at all. Mali has denied their presence in the country, as has Burkina Faso, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and Sudan; alternately, it does seem to be confirmed they are operating in the Central African Republic. None of this has stopped Western sources from making a variety of sometimes bizarrely specific claims. Some of these include El Pais reporting the presence of 1,400 mercenaries, US Africa Command General Stephen Townsend saying he has “reason to believe” that Mali is paying Wagner $10 million per month, and the “Armed Conflict Event and Location Project” claiming that “71% of Wagner's involvement in political violence in Mali has taken the form of violence against civilians.” This last claim is particularly absurd, since France could not tell the difference between a wedding and a “terrorist gathering,” yet this ACELP purports to know the specific percent of violence which is targeted at civilians.

Much is made of Wagner’s real or imagined links to the Russian state. Wagner boss Yevgheni Prighozin is frequently called “Putin’s Chef” because they once met when Putin dined at his fancy restaurant. For all the speculation, it seems the most likely that Wagner is a normal mercenary organization. They clearly have “Kremlin ties” in the sense that everyone [including pro-Russian sources] know they are fighting in Ukraine, obviously for pay because that is the business they are in. In that capacity they are mercenary troops of Russia. It stands to reason they don’t deploy to any conflict without tacit Kremlin approval because that is the nature of being a mercenary; mercenaries always need permission of the country which hosts them. Almost every country has laws about its citizens participating in conflicts which depend on the government’s view of the conflict. This is why the notorious American mercenary leader, former Blackwater owner Erik Prince is now based out of Dubai. If Wagner mercenaries are operating in West Africa, it would have to be with some form of permission from their government, though it doesn’t mean they are there to serve Russia’s geopolitical interests, just that they don’t actively harm them.

For a variety of reasons it is plausible that Wagner is operating in West Africa. Most of all because this is their business, and the rule of these states is being seriously challenged by terrorism. However, anyone you might call a “noticer” will be skeptical of any claims that the Western policy class makes about malign Russian influence. Like so many things, the government has destroyed its credibility on “Russian influence” to such an extent that any statements that are not wholly confirmed by my eyes are worthless. Regardless, It has always been the prerogative of governments to hire mercenaries, though as Machiavelli would tell you, it is often a bad idea. If the juntas in these countries do not have the legitimate authority to hire mercenaries they also do not have the authority to employ their own soldiers.

Western sources are making absurd claims about Wagner’s employment, such as the pro-America Ghanian President claiming Wagner is operating in exchange for mining rights. If Wagner wanted to be in the mining business, it would be in the mining business. However, Russia does have mining interests in the region, including one firm being awarded a new contract in Burkina Faso. El Pais reports of the following Russian interests in Africa:

“Rusal extracts bauxite in Guinea. But there are others such as Norgold, Renova, Alrosa or Vi Holding operating in countries like South Africa, Angola, Burkina Faso, Zimbabwe and the Central African Republic, where they extract gold, diamonds, manganese and platinum.

In the hydrocarbon, gas and oil sectors, a handful of Russian companies have become strong in Africa, such as Rosneft, Gazprom and above all the giant Lukoil”

Of course, this is what everyone involved actually cares about. It does stand to reason that Russian private military contractors are there protecting these economic interests [which is what all multinational corporations do in dangerous areas, unless they have in-house security.] You would have to be crazy to hire local security somewhere like the Sahel, where it is functionally impossible to vet a local for ties to extremist groups or bandits; further, even if a local has the intention of being honest, he has family members who can be threatened or abducted. Alternately, if a Russian or other Eastern European tries to run off with the gold or diamonds, the company knows where his family is. Man’s willingness to kill for gold is one of the most well established features of humanity, so it is not some sort of nefarious plot for someone to protect a gold mine with mercenaries.

A Foreign Policy article I will cover in depth further down criticizes Wagner’s “transactional” approach to the region [it is literally a business; also people who say that are always criticizing someone for not hypocritically using ideology as a cover for avarice,] and goes on to say,

“On the contrary, the Wagner Group has acted in a predatory manner, siphoning resources in exchange for security. Once the resources and minerals are depleted, Russia will withdraw, leaving behind a volatile region that could develop into a safe haven and sanctuary for jihadi groups.”

Firstly, could develop into? As opposed to now? They are going to ruin the thriving and safe secular civil democracies that France left in place? The more noteworthy part, though, is that they expect Wagner to rapidly deplete the minerals. This is another example similar to what I call “Schrodinger’s war effort” where Russian is simultaneously incompetent but also has such superpowers they can rapidly collect all the minerals from a region France and the rest of Western Europe has been fleecing for 150 years without running out. This is the source of the gold Mansa Musa brought on his famous pilgrimage to Mecca in 1324 where he carried so much his prodigious wealth collapsed the economy of Cairo; it seems unlikely Wagner depleting the resources of the area is an immediate problem, but I suppose we should never underestimate what our scribblers want us to believe Russians are capable of. Still, if Wagner is operating in these countries, there surely is some degree of precious mineral theft from the locals by Wagner mercenaries, as that is the nature of both mercenaries and of men as a whole.

Diplomacy by Daylight

In early February 2023, Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov went on an diplomatic trip through the Sahel region. Russia has long been involved in Africa, both in search of mineral wealth and exploiting resentment against colonialism for influence during the Cold War. As I explained early in the Russia-Ukraine War, Russia has a very different reputation in Africa than in the West. The Western thought class would say that this is because Russia will amorally support any autocratic regime which is friendly to them, which is basically true; unlike the West, they at least do it without making everyone experience soul-crushing hypocrisy. Africa’s balanced view of foreign powers came into focus when the whole world was angry that many African nations refused to condemn Russia’s invasion of Ukraine or take part in the sanctions regime. In fact, as the Western imperialist thinktank Brookings reports, 51% of African nations voted to condemn Russian, compared to 81% of non-African nations. This may have something to do with affinity towards Russia, though it seems more likely that African nations both wanted the ability to settle their own border disputes and further understand their vulnerability to the world turning against them in this fashion. Beyond which, Africans are constant victims of Western hypocrisy. They also may have just bucked at the fact that they are always being praised or scolded as if they are children, and never considered independent actors with their own views and concerns, so they sat this one out [Eritrea was the only African country to vote against the resolution, the rest who did not approve either voted to abstain or did not vote at all.]

For all the talk about “universal values” and “human rights,” France has been happy to support a junta in Chad for decades because it is French-aligned. To the extent that France was earnestly trying to support democracy, civil institutions, economic development, and fight terrorism in its former African empire, the present round of that effort has clearly failed about as drastically as possible. It wouldn’t be possible for the region to be much less stable or more troubled than it is now. In this instance, no one is trying to blame Russia for the pro-French governments falling, but they hate to see the countries improve their relationship with Russia. Thus, Russia is seen as a villain for entering into the mess the French left.

Sergei Lavrov is one of the world’s most experienced diplomats, and had a successful tour through the Sahel, shortly after visiting South Africa, and following prior recent visits to other parts of Africa and the Middle East. He visited Mauritania and Sudan, pledging to aid the fight against Jihadists. [Note: shortly before publishing, Sudan’s military agreed to a plan to host a Russian Red Sea naval base on the country’s soil; it awaits approval of the civilian government.] Most importantly, for our purpose at least, he went to Mali. In Mali’s capital Bamako Lavrov stated,

“We are reliably meeting Mali’s needs to ensure its security and defense capability. With our support, the Malian leaders have achieved clear successes in countering terrorism. We will certainly continue this cooperation.”

The government of Mali has been positive about its relationship with Russia. The Malian Foreign Minister thanked Russia for its provision of cereals and fertilizer to the impoverished nation, and further said,

“Mali stands in solidarity with Russia on the issue of sanctions…We are not going to continue to justify our choice of partners... Russia is here at Mali's request, and Russia responds effectively to Mali's needs by strengthening its defense capabilities,"

This is a prime example of how Western governments drive poorer countries into the arms of their rivals. A country like Mali cannot afford to just have fewer cereals and fertilizers. They can’t just choose to pay more for food to uphold “universal values.” Mali also lives under the risk of threats of sanctions now that it has stood up to the French, and further expelled the UN Human Rights chief on the grounds he was unfairly seeking to undermine the regime.

All of these things are reasons they need Russia; reasons that wouldn’t exist if the West behaved differently. For Russia, countries such as Mali represent mineral opportunities and markets for raw and manufactured goods, most of all weapons. While like other powers Russia uses weapons sales as a form of soft power, Russia’s weapons industry is also highly profitable to the state and they often appear openly be in it for the money [as I explained regarding the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict.] Further, Russian weapons are much, much cheaper than their Western counterparts, making them a better match for impoverished countries such as those in the Sahel. They are also easier to maintain and come with fewer conditions. Junta leader Goita certainly seems happy with them, saying during last month’s “Army Day,” “The military success we achieved in the past two years outweighs anything that was done in past decades. Our weapons are the pride of the entire nation,” referring to Russian heavy equipment including Russian Sukhoi fighter jets the country has received over the last few years. He offered no evidence that his junta has improved the security situation, though the good thing about leading a junta is you don’t have to prove anything.

The Groans of the Scribbling Class

Russia’s actions in the Sahel are mostly how a normal country behaves. That is to say, they go around speaking to people and making agreements and working out if there are mutually beneficial interests. It really shouldn’t be anyone else’s business if there are, if these countries are to be considered sovereign. You may be wondering why it should matter to the man on the street how the Sahel aligns. It really doesn’t, though human rights problems are always sad; however, I can guarantee these coup governments are relatively less bad than Al Qaeda or The Islamic State. Still, the empire managers, think tankers, and other in the op-ed pages are quite unhappy with this turn of events, despite that France’s leadership had failed to essentially the greatest extent possible and thus a different course was inevitable. Most of it is what you would expect if you have ever read The New York Times or The Washington Post: blah blah blah Russia bad, yada yada yada credibility, human rights, universal values, it’s different when the French accidentally bomb weddings. El Pais produced this gem of a quote from some women who is charitably considered to be a scholar:

“Russia is leaning on the image created in Africa by the Soviet Union, at a time when Moscow supported many liberation movements, trained students and built hospitals. It is perceived as a kind of older brother, a defender of Africa’s sovereignty, embodying an alternative development model to the Western one. But this idealized vision does not match the geopolitical and moral realities of today’s Russia that has unleashed the war in Ukraine.”

Right, so the Soviet Union- which controlled all of Ukraine- was fine, but modern Russia fighting over an eastern portion of it is a game-changing moral abomination. The racism and/or chauvinism of how much more these people care about what goes on in Europe never ceases to amaze me. What were the geopolitical and moral realities of the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan? Or for that matter sending in tanks to put down the Hungarian uprising? Of course they don’t think at all about applying such judgement to Western invasions of non-European countries.

Even more ridiculous than this is a piece Foreign Policy published, by a man named Colin Clarke. The article is titled, “Russia’s Wagner Group is Fueling Terrorism in Africa.” I would normally discourage you from reading Foreign Policy, but this piece is too funny to miss. Firstly, of course, terrorism was a major problem that was growing explosively long before Wagner allegedly entered the picture. Secondly, the mainstream view is that the French-led attack on Libya is what destabilized the Sahel and fueled terrorism. Granted, that was years ago and this is now, but regardless, by accepting this job- if they did- Wagner inherited a massive problem almost entirely created by the French. And thirdly, just of criticisms regarding title and author, this individual works for something called Soufan Group, which is itself a security contractor; he is attacking a business rival and the bio says this as if it gives him credibility, not as if it is a conflict of interest disclosure. A Western-aligned country in Africa might hire his company to deal with these exact problems; I don’t know if his company has in-house mercenaries, but if they don’t they surely sub-contract them. Clarke writes,

“Research that examines best practices and lessons learned from all insurgencies waged between the end of World War II and 2009 suggests that the Wagner Group’s approach in Africa is likely to further destabilize the countries where it operates. Historically, collective and escalating repression against insurgents as well as a singular focus on kinetic operations have failed to quell conflicts and, more often than not, have prolonged them rather than contributing toward their cessation. The Sahel is no exception.”

Firstly, he is one of the researchers he links to, further just selling his own consultancy. Without reading the book, I don’t know which counter-insurgencies he considers to have been successful in that time period, or after, but they all seem to go pretty damn poorly. Further, Wagner, if there, is one component of a strategy. Unlike an imperial power imposing its wisdom by violence on a lesser people, Wagner would be hired as a private security firm to deal with security. It is not their job to fix the problems of Mali, it is their job to conduct the necessary security operations while the government of Mali chooses its own path. He continues,

“First, human rights abuses perpetrated by Wagner Group forces are likely to contribute to grievances among the population, which in turn provide fertile ground for terrorist groups like al Qaeda-linked Jamaat Nasr al-Islam wal Muslimin and the Islamic State Sahel Province to recruit new members, providing much-needed resources to these organizations. In Mali, Wagner’s forces have been accused of mass atrocities, torture, summary executions, and other brutal crimes. Since December 2021, more than 2,000 civilians have been killed in Mali, compared with 500 individuals over the previous year.”

Right, and this information is coming out of terrorist controlled areas, where you yourself just stated terrorists use such claims for recruitment purposes? There’s a bit of a flaw in the sourcing of that argument.

“Since private military contractors will not be held accountable for any of these crimes, as the states where they are operating have weak investigative capabilities and judicial systems that are not independent, the sense of impunity is only likely to incentivize further marauding. Moreover, there is still a gray area regarding where private military contractors fit in terms of accountability and international law, as they are neither civilians nor lawful combatants to conflict.”

Oh, and I suppose the French are famously held accountable for what they do in Africa? I seem to remember that in Iraq, where his company “consulted,” the US withdrew because they would no longer have immunity. On top of which, international law does not apply to domestic conflicts, and terrorists are not legal combatants by any standard. I don’t doubt that Wagner would functionally act with impunity in Mali or Burkina Faso, but the enthymeme here that this is drastically different from relying on Western powers for counter-terror assistance is egregious.

“Third, since Wagner mercenaries are only providing security cooperation along purely kinetic lines—eschewing good practices of counterinsurgency training, such as strengthening the rule of law, promoting good governance, and establishing an independent judiciary—any perceived security gains will be fleeting.”

This is like the “Defund the Police” people talking about “root causes” for spiraling homicides in Chicago. None of that works unless there is security, and it isn’t the job of the people who provide security to do other things. You can’t fix the root causes unless there is the security necessary for economic and social development. Also, in this instance, the root cause is literally France.

He concludes,

“Washington, Paris, and their allies should reconsider their respective military drawdowns from the Sahel. By ceding ground to the Wagner Group, the West is opening the door for Moscow to consolidate influence in the region while simultaneously making the region more dangerous.”

Translation: countries who will hire the Soufan Group should be the ones involved in the region.

Even by the standards of the scribbling class, this is wildly shameless. The West, France specifically, has already failed in the Sahel. This is not a problem Russia caused, and in fact, Russia opposed the destruction of Libya and the policy of supporting jihadists in Syria. The root of his argument is that an imperial overseer needs to try and set up the very institutions that just failed to defeat terrorism in the Sahel. It is for the governments of the Sahel to try and fix this, Wagner is just [once again, allegedly] involved in the amoral work of ‘merc’ing, and they are probably actually much more effective and professional than local tribal militias or whomever else the government might hire in their absence. If they can make the same government stand for a period of time, that is the main form of stability, something France clearly failed to do in this land that had 9 coups or attempts in a 3 year period.

Conclusion: A Legacy in Ashes

When Europeans reached the Gulf of Guinea, the broader Niger River Basin and western Sahel was already in a state of decline. However, it had once been home to some of Africa’s greatest and most “civilized” [by our standards] empires. Not a lot of sub-Saharan Africa supports large scale settled populations, but this region could feed itself and has a wealth of natural resources, including the minerals which are so coveted. True, the revenue decline was inevitable once sea shipping became regular and Timbuktu no longer represented an important caravan route across the desert, but the region has everything necessary for success, besides the ability to make its own decisions.

The legacy of French imperial mismanagement will long loom over the Francophone West Africa, and extractivists from across the world will continue to covet its deposits and send children down mines for as long as there is poverty and the desire for profit. The unstable nature of the region is not inevitable, it is a result of the alternating avarice and then disinterest of outside powers. The consequences of overthrowing Gaddafi’s Libya should have been obvious to anyone who seriously studied the situation; a thousand trained armed men, such as his Tuareg Guard, able to act in unison, can become a serious threat to any region, most of all a fragile and impoverished one with vast wasteland. Russia is not a solution to the region’s problems. However, being treated like an equal partner to solve their own problems could be. If Mali, Burkina Faso, and Guinea can successfully attach their capitols by train as they hope to [and as the French should have done 100 years ago], they may have some real hope for economic development, especially given that it would provide access to the sea for the two landlocked states. No one can know what the future holds, and their prospects are indeed grim, but we have seen that the French system of suzerainty has been condescending, exploitative, and ineffective. Factions will surely again change in these countries, and some day French alignment is likely to be the most popular again. Hopefully by then the French have fully cleansed themselves of the imperialist and paternalistic notions they finally seem willing to shed, and perhaps than France can be a good partner to the West African countries of its former empire. For now, time will tell if drawing closer to Russia makes things better or worse; I fear it will upset the West far more than it is worth.

[Note 3/28/23: a video had been added at the end showing an advisor in Mali praising Wagner. I was incorrect about the date of the video, and further the account has been removed from Twitter. I have removed that addition to the article.]

Thank you for reading! If you enjoyed this content please subscribe and share. My main content will always be free but paid subscriptions help me a huge amount. [Payment in West CFA Francs preferred.] I have a tip jar at Ko-Fi where generous patrons can donate in $5 increments. Join my Telegram channel The Wayward Rabbler. My Facebook page is The Wayward Rabbler. You can see my shitposting on Twitter @WaywardRabbler.

The update incorrectly cites Goita. Instead it is Adama Ben Diarra alias "Ben le cerveau", Member of the National Transition Council.