Cowardice in the Face of Weakness

The Corrosive Impact of Globalized Charity in "The Camp of the Saints"

“There is nothing that uses itself up faster than generosity; for as you employ it, you lose the means of employing it, and you become either poor or despised or else, to escape poverty, you become rapacious and hated…It is wiser to live with the reputation of a miser, which gives birth to an infamy without hatred, than to be forced to incur the reputation of rapacity because you want to be considered generous, which gives birth to an infamy with hatred.” - Machiavelli [The Prince, XVI]

A new translation of the legendary long-suppressed novel “The Camp of the Saints” was released by Vauban Books on September 16th. I have decided that since plenty of people will surely review it, for now, beyond my normal Twitter review, I will make use of my academic background to write something like a proper piece of literary criticism on the text. If you are an editor, I would consider offers to write a normal review for your publication. My DMs are open on Twitter.

You don’t need to have read the book to understand this essay, though I recommend reading the book in general. The new release is available on Amazon [currently sold out.]

The 1973 novel The Camp of the Saints by the French author Jean Raspail is primarily known as a fable about the dangers of mass immigration. While the plot is about an armada of les damnés de la terre setting out from the Ganges for “a land of milk and honey,” much more of the story is about the world’s paralyzed reaction in the face of this unexpected development. The text has great thematic depth, most of all about how in the West, taken in by fine professions of universalism and the brotherhood of man, we have lost faith in ourselves and become ashamed of our heritage, and are thus on the path to civilizational suicide. While one could argue about the book’s degree of prescience, it undeniably features a diverse cast of characters types we have all encountered, most of all during the riots of 2020’s Mostly Peaceful summer and the years surrounding it: downwardly mobile violent white nihilists, ultra-wealthy men of minority heritage driven by hatred, liberal “thought leaders” telling us to accept sacrifice in the name of historic wrongs, social justice activist clergy who don’t seem have any traditional conception of God, spineless performative politicians who know they are surfing a wave of public opinion towards disaster, and many more. Throughout the text we see men whose souls are sapped, corrupted, and suppressed by a constant feature of modern life in an instantly connected world: international pleas for charity broadcast into our homes, implying guilt for what we have and demanding we open our hearts and wallets to an endless void of suffering. All of this despite that such actions seem to never make anything better and to only breed resentment and ever more children among those who receive the charity. In the novel, in the end, after a lifetime of sapping and conditioning, it is too late when the public hears the words of the novel’s French President, who after much prevaricating finally tries, and fails, to be brave, saying, “Cowardice in the face of weakness is one of the most active, most subtle, and most deadly forms of cowardice” [251.] Modern sentiments and technology have moved Western civilization from the norm of a small amount of charity in your local community, if you can afford it, to a constant global catastrophe that is more than the individual is equipped to handle, and too much of the public has responded with self-loathing and nihilism. Such cowardice in the face of weakness may well be the end of us.

The theme of the corrosive impact of global charity on society is presented near the beginning of The Camp of the Saints, with the first character, the professor Calgués, reflecting on his family’s enormous peasant chest and the linens which his grandmother used to give the poor, who seemed to ceaselessly multiply until they could not be helped,

“Is not unbridled charity a sin against oneself? But soon there were too many poor. You didn’t even know them. They weren’t from here. Just nameless people…They forced their way in by the thousands, with an unerring knack. They got in through the letter boxes, begging for help, their dreadful photos bursting from the envelope every morning to make their demands on behalf of this or that association or charity.1 Everywhere, they insinuated themselves, in the newspapers, the radio, the churches, the factions - they were all you saw anymore, entire nations that no longer even needed linen but instead checks with their name on it, bristling with heartrending appeals, appeals that almost seemed like threat. And it got worse, there they were on television, on the move, dying by the thousands, the anonymous slaughter having become a non-stop spectacle, with its professional apologists and masters of ceremony. The entire world was overrun by the poor. Remorse set in everywhere. Happiness became a defect. And what was one to say of pleasure?…In short, one no longer even felt better by giving. To the contrary, one felt diminished, shameful” [62-63.]

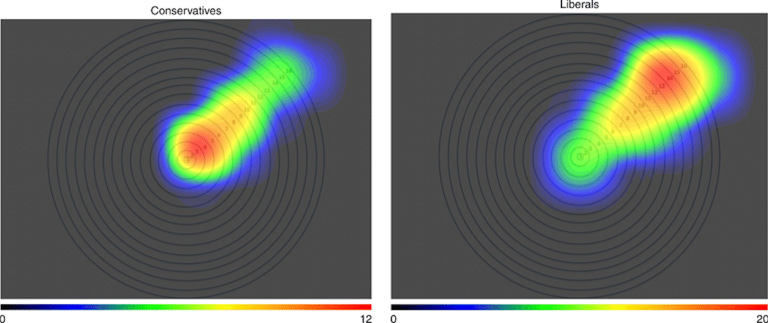

This novel is set in a near future, which is perhaps meant to be around the year 2000. The easiest but rough indication of the year is that old men say they were young men at the time of the Second World War. What Raspail describes is indeed what happened in the decades following the novel’s publishing, though he couldn’t imagine the internet’s contribution to spreading the message of global suffering. Fortunately, there has been a degree of push-back, at least moreso than in the novel. For example, the Starvin’ Marvin episode of South Park, pictured above, is from 1997, a plausible year for the novel to begin, and is a parody of the Christian Children’s Fund and sad commercials showing an obese celebrity around starving children demanding your money. In the novel, there is brief mention of one Struthers-esque celebrity women who it describes as “rushing after her ‘poor little dears’ like a safari enthusiast after its game” [176.] The South Park episode provides fairly deep insight into the problems with the international charity industry as a whole, including that it does more to make the impoverished people realize how wealthy we are than it does to help them, and instead of gratitude they end up viewing us as selfish. This is not, by the way, meant as a criticism of the Third Worlders, given that the assessment is broadly accurate. These programs primarily exist because of how they make us feel, and it is something like a narcotic, where our fortitude and wealth flow outward. For one example, building houses in Mexico is a common Christian charity activity in the United States, but from what I’ve heard, all of the research on this is about how it positively impacts the American teens, and little thought has been given to the fact that it depresses the local economy and prevents economic development because no one there will maintain their houses or employ local contractors, they simply let their houses fall down until a bunch of inexperience teenagers come build them another shitty new one for free- a microcosm of the premise of “giving back” to the Third World generally.

In the novel this has all been taken even farther than it went in real life with famines and humanitarian campaigns becoming ever more persistent2. The prior Pope, caught up in the mania, had sold off all of the Vatican’s treasures, only to find that the money did not even cover the rural budget of Pakistan for a year but that he was now hated for his erstwhile wealth [63.] People have of course gotten no smarter about such things, still thinking one could solve this or that problem by seizing the wealth of billionaires, despite that simple math shows on that scale it wouldn’t go very far at all and it is currently tied up in funding the economy. I hate Jeff Bezos as much as the next guy, but you can’t actually just donate the value of Amazon to poors and have the company continue to have capital to function- a classic “eating the goose that lays the golden egg” situation.

The current Pope in the novel is a Francis-like figure from Latin America, ironically called Benedict XVI, who is interested only in what we now call “Liberation Theology,” to the extent he cares about theology at all, and convincing the “haves” to share with the “have nots” even to the point of putting the general public in poverty while doing nothing to increase the economic productivity of poor areas. The text abounds in such people, with the author, a man of deeply conservative Catholic sentiments, showing the way this has corrupted Christianity. Supposed religious figures who have gone secular are some of the worst offenders in encouraging entire villages in India to head for the boats with no future plans, while others welcome this primarily pagan crowd flooding Europe on the grounds that it will liberate everyone in some spiritual sense. In the real world it is also the case that religious charities, contracted with the government, do most “refugee resettlement” in the modern United States, and it often seems as if many of them are not religious in the way anyone would have understood 100 years ago and many likely don’t believe core precepts of the religion, they are simply liberal universalists who think the path to salvation is material equality between man- a particularly lame heresy, if ever there was one. They, then, don’t work towards the salvation of men’s souls, but the salvation of their bodies, though there is a degree of haranguing implying that this will expiate the giver of his guilt for his relative wealth, despite that he is unlikely to bear a meaningful amount of economic “guilt” for his meager wages.

It has become increasingly common among liberal Christians to have such “universalist” views of salvation- at least for the poor and minorities- while viewing Christianity as a sort of “kindness club.” Of course, behaving well towards your fellow man is important within Christianity, but there is a lot more going on there and actually worshiping, believing, and following various dogmas and moral prohibitions are all key parts of the whole thing. The most egregious example I can think of came from the 2020 lockdowns when some liberal Protestant pastor quite notoriously made a claim like “for any church worth it’s salt, Sunday morning is the least important time of the week!” The meaning here being that any good church is so busy with charity, or more likely social justice activism, that the religion part is insignificant. Of course, for that guy’s church, Sunday probably was the least important and most harmful part of the week, with the sermon spent telling you bizarre things like that enforcing the law is racist or that Jesus was a black sodomite or that borders are literally Hitler. It has become a sort of secular clergy of depraved “levelers” discouraging men from having requisite focus on God, themselves, their family, and their community- the things which build a functioning society. Instead, to them religion is instead about favoring what by the final 2011 preface Jean Raspail had taken to calling “Big Other.” As with many things in this text, it is hard to know how prescient the author was or if the rot was farther along in the early 1970’s than one would imagine; as someone who reads a lot of old texts, my assumption is that it is primarily the latter, even if most men were choosing to be blind to the threat.

It is hard to parse out how to behave in a world where charity has become a constant expectation, in a way that goes much farther than the tradition of tithing. For most of history, people were not made to think this way at all. Modern charity as we know it largely began with Christianity- before that man had pity for his fellow man and governments or others might feed the poor to prevent revolts, but the spirit of charity is largely a Christian invention. However, the majority of people were so poor that for most this was something more like hospitality, you know trying to feed a starving man passing through and sending him on his way with an extra blanket if you could afford it, which you couldn’t. General kindness as well as a sort of social safety net encouraged the helping of neighbors. The only time one might hear about poor people in distant lands would be at church on Sunday. The two notable examples I can think of- and I don’t have sources but it must have been that way- were speaking of the need to save Christians in the Holy Land during the Crusades and probably raising money to send missionaries to the Americas. Of course, both of these things are now seen as great historical sins by the people who currently harangue us about helping people in other lands. Picking out some other well-known issues, we know that the Irish Potato Famine became a big charity cause, and that also that by the mid-19th century when Dickens was writing at least Ebenezer Scrooge was highly annoyed by people going around collecting charity. In Dostoevsky’s Demons, which Raspail briefly references as showing the beginning of ideologies destroying Western society [the point of that novel,] the “Boomer Libs” and left wing nihilists get together for some big charity ball for the province’s “Poor Governesses,” a cause which is never properly explained, being as a governess is just a woman who tutors rich children in their own home and if they are so impoverished these rich people should just pay them more, not have a fundraiser ball [the cause is meant to be vacuous in the novel.] From Tolstoy, a contemporary of Dostoevsky, we also know that at that time in Russia they experienced what we would now call a “Current Thing,” from this passage in Anna Karenina,

“In the milieu to which Sergei Ivanovich belonged, nothing else was talked or written about at that time but the Slavic question and the Serbian war. All that an idle crowd usually does to kill time was now done for the benefit of the Slavs. Balls, concerts, dinners, speeches, ladies’ dresses, beer, taverns - all bore witness to sympathy with the Slavs” [7713.]

This refers to freeing the Serbs from Turkish domination, and it is notable that for the valid criticisms of that particular social mania and the ensuing military adventure, the core purpose was to liberate their brethren and co-religionists from an “Other,” and was still distinctly in-group preference.

A number of years ago, while doing research for a Centennial Memorial for a young man from my town who went missing in action in World War I, I discovered something similar in my own town: monks had came around amidst the war to raise funds for victims of the Armenian Genocide:

Again, though, this is for people seen as being like you being victimized by someone you see as not being like you, and further is one educational presentation you choose to go to [not to mention, we were at war with the people doing the genocide.]

In the above instances, people were exposed to the horrors of the outside world not involving themselves perhaps once a week, or in the form of little newspaper items. They gave money to specific things, or just put an extra coin in the church collection. With mass media, particularly after World War II, it became a global “polycrisis” blamed on “Imperialism” and “racism” [not entirely inaccurately] where everyone was meant to carry the world’s misery daily to be a good person, despite the fact that half the “benefits” are rich people stuffing their faces or some kind of other carnival incentive, like the boys in South Park donating to Ethiopia to get a watch or Lindsey in Arrested Development:

In the novel, the way the media turns the polycrisis into the omnicause is called “the radio game” and Machefer, Raspail’s one journalist protagonist, describes it as follows,

“It may be fashionable, but antiracism isn’t very fun or profitable to hear about, they know this, so they make a game out of it! Since they started playing this game, the people have been ground down. Cancer? A game. The Sahel? A game. Poland? A game. I could go on…Showmen are sent out to collect money; ordinary folk, bored stiffed, are dragged out onto the streets to buy tickets to support the cause; they flash their lights in time to show their solidarity; entire neighborhoods and towns are transformed into teams, competing to see who can fill the most trucks with donations; then come the telethons, running day and night, with lots of singing and entertainment to liven things up…At midnight, it’s all over, A good time was had by all. And what has all that accomplished? We’ve muddied the issue with all the fuss and fanfare.” [132]

There is no clearer example of this than the “Live Aid” concert, which fit this description so accurately one almost dreams if the creators had read this text they would be too ashamed to have put them on at all, but of course they wouldn’t be ashamed. Did those do anything to end the famine in Ethiopia, or did “Live Earth” do anything to help the environment? Who knows, and who the hell even cares? What they did was “raise awareness” which is to say they made everyone feel temporarily good but overall worse while directing money to an army of incompetent, over-educated pantsuit women and cuckold men who can’t find a sense of purpose but for thinking about the poor whoever. It needs to be said again, none of this charity makes the global poor happy, it just makes them realize that despite being a talentless moron without a real job whatever average Westerner partaking in misery tourism in their country is wealthier than they can hope to be. Meanwhile about half of people in the West become chronically unable to enjoy life knowing that the poor people of South Slobonia are starving, despite that they have no connection or obligation to those people and it doesn’t make a difference if the country is fictional.

Really, the petitions for this or that disadvantaged group of people never stop, and we like to imagine at worst the harmless whims of the well-intentioned. However, it is all too much, as Raspail writes,

“Thousands of signatures were collected by hundreds of committees…And heading these lists, the familiar names of all those, who had, for years, sapped the conscience of the Western world by dint of their endless petitions. Big deal, some people thought, none of it serves any purpose! Or does it? Drop by drop, the poison acts painlessly, but at the end of the day, it still kills” [186.]

It isn’t just the celebrities, media, and professional do-gooders who put this attitude of ever seeking out human misery to find and inconsequentially contribute to “solving” into public life. This sentiment dominates society and the institutions. I remember when I was in first grade the Oklahoma City Bombing happened, and instead of trying to shield children from it we were meant to take part in some sort of class fundraising drive. I remember particularly that older kids were having a bake sale for the same cause, and a student in my class was in anguish about what amount of money he should save for the class fundraising drive and what amount he could spend at the bake sale, for the same cause, because at age 6 we were already supposed to be learning how to compete with other grades to raise the most money for victims of terrorism thousands of miles away- who it must be said were at least Americans! So here is this 6 year old drowning in the moral quandary about if his same donation should buy him cookies or get him nothing at all. This is meant to build character! They have also spent 75 years trying to get kids to go around collecting money for UNICEF on Halloween, because why should you enjoy anything without thinking about the pictures of starving children on other continents! I must admit I myself take part in such activities, having my kid do one of those Samaratin’s Purse Christmas boxes, figuring it is a good lesson about generosity, but as I write this I am telling myself that a Christmas present keeps it within appropriate perimeters for teaching the moral value of giving without drowning her in the weight of the world’s misery.

Some of the biggest offenders in creating this society of toxic empathy are teachers, who of course instead of teaching students to value faith and family see their role as shaping them into “good humans” in some vague secular way, most of all a lifetime of antiracism training. Following a radio editorial from one of the most popular “thought leaders” in the novel, Raspail describes how “thirty-two thousand seven hundred and forty-two” schoolteachers immediately decided their composition the next day would be making the kids write about the lives of the migrants on the ships and if they would let some of the armada’s passengers stay in their home. As the narrator describes it,

“Unbeatable! With a child’s naïve soul and sensitive heart, the dear little angel will cover four pages with infantile pathos to make the concierge cry…This is how men are made today. For even the tough, heartless kid - that is, one who has exactly what’s needed to succeed in life - is forced to take part, since children hate nothing more than to stand out. He’ll have to get with the program and, like all the rest, hypocritically sweat over the same damned humanitarian essay.”

Of course, it isn’t easy for any parent to explain what is wrong with this,

“And father, who knows what life is all about, will read the A+ masterpiece, and, frightened though he may be (if he has any imagination) at the prospect of 8 members of this foreign family coming to share his three-room apartment with kitchen, he’ll keep all that to himself. One must not disappoint the little angels, one must not scandalize them, one must not dirty the purity of their feelings, even if they grow up to be fools…

Now multiply a million times over the inane compositions approved by a million limp fathers and you’ve got an all-around rotten climate” [118-119.]

Of course, all the high school teachers also get into the act, since it’s the topic of the day, finding a way to incorporate antiracism into every subject, not wanting the children to become dreaded nativists with the sense to not take 800,000 starving uninvited humans into a country that has in no way prepared for them.

This is all standard fare in schools. Universities, instead of being happy that you are a good student and perhaps also like sports or other recreational activities or even have a job contributing to society, want to know that you have taken part in public service and activism to slay the evils of the society which has allowed you to hopefully grow up in comfort. At the university it continues, with public service, real or imagined, being a common part of courses whether or not it is relevant. What all of this does is create students who lack in sense but have an abundance of superficial empathy for the “oppressed” across the world and who can’t think straight about what matters in their own lives under the weight of the suffering of others, despite that more than anything having your own orderly, productive, and happy life is the “rising tide that lifts all ships.”

If you will allow a digression, I must tell an incredible story which was recounted to me in my own life, demonstrating just how advanced and nefarious this process really is. When I was near the end of college, which was, it should be said, during the heart of “The Great Recession,” my friend Hunter- a wealthy white man who would be said to be lacking in this type of “empathy” and thus also the sort of person who gave Raspail some hope for society- was in a class where they were assigned a project to design some sort of contribution to charity. Some young women in his class decided they would do a project of collecting cans to send money to feed starving children in Myanmar or wherever. As it turns out- and I had never thought about this- the reason that despite students walking around college hill drinking all night and chucking their beer cans anywhere they wished, one never saw cans in the morning when walking to class half-drunk and half-awake was because some old man known as “the Can Man” woke up at dawn every morning and went around college hill collecting cans to sell4. The young women, presenting their project, told what they considered to be an amusing anecdote about how this Can Man got angry about them taking the cans, explaining he relied on this income, and they had something of a confrontation but did not give him the cans. Hunter interjected with a great deal of indignity that it is ridiculous to take away the source of income of an impoverished member of our own community in order to send that money into the void of Third World hunger. The professor then offered the young women assistance with the statement, “Oh, I know about that guy, he abuses Veteran’s benefits.” To this bizarre justification, Hunter responded, “The guy is out picking up cans every morning, he is obviously not ‘abusing veteran’s benefits,’ and that he might have taken a bullet in ‘Nam does not somehow make this story better.” The story ends here, as Hunter, again not any sort of bleeding heart, was so perplexed and angered he left class to smoke two cigarettes, not so different from the tough schoolchild Raspail imagined working at his humanitarian essay, but old enough to be allowed to walk out.

Himself impervious to humanitarian propaganda, Hunter had the normal reaction to think the work of a man in his community was more important than a charity for some distant Other, particularly given that this project was meant to teach an abstract lesson [and with a different professor, what a good lesson it could have been, that someone in the community needed the cans!] This degree of what is generally called “out-group preference” only comes from a lifetime of subtle brainwashing and global charity propaganda. Here, I must share the meme:

In The Camp of the Saints we run into this element of France’s decline almost immediately, when the literature professor Calgués is confronted by an antifa-type miscreant on the day which the armada arrives. Upon asking him how he feels a kinship with these people who have nothing in common with him, as part of a long, Sartre-inspired rant, the young man says,

“My real family is all the people coming off those boats. Now I have a million brothers, sisters, fathers, and mothers. A million wives. I’ll have a child with the first one I see, a dark child, and then I’ll no longer see myself in anyone.”

When asked why he wants the migrant mass to destroy everything without knowing or understanding it, and what this means for his fate, he responds,

“Because I’ve learned to hate all of this. Because the conscience of the world makes me hate all this.” [59]

The young man’s soul, self-worth, and love for his home and family have been entirely destroyed by the combination of constant demands of charity towards world’s sufferers and an ideology that posits all men and cultures are of equal value and thus he has only grown up relatively prosperous due to unfairness. The grand irony is that he has a degree of self-awareness that everything will be rapidly looted and destroyed and then the migrants would not actually have a good life there, but he doesn’t care, because the “conscience” of the world has made him hate everything. This would seem like an improbable and rare sort of white person to me if not for the fact that we all lived through 2020 where such degenerate creatures were briefly ascendant to the applause of the whole range of “thought leaders” and politicians one sees in this text.

More than anything, they are unhappy people because they have been fed misery and nonsense their entire life. Jordan Peterson’s esteem has fallen over the years as he continuously comments on things about which he knows nothing, but his original fame was for simply explaining that classic stories explain universal human experiences, and young people found this profoundly inspiring because it was the first time anyone had told them anything true and positive which seemed to say there was a world worth living in and they could be a valuable part of it- things which every young child should learn from stories, told in earnest, not “deconstructed” by post-modernists. Raspail describes his antifa-types on migrant apocalypse D-Day,

“There was really nothing left but to drown oneself in the sticky-sweet syrup of human misery, most often nicely set to music, and it was there that dissatisfied souls took refuge, for they had been taught nothing else. It never occurred to anyone to measure the notion of misery against oneself or the past. This world only remained standing thanks to high doses of misery-dope, like a needle head who needs to shoot himself up with heroin to keep going. the fact that it was often hard to come by close to home mattered little, for nothing gets in the way of an addict in withdrawal, and these poisons were easy to import, with never any shortage of dealers” [274.]

It is indeed all that anyone has been taught, which is why the hordes of mundane liberals love nothing more to be scolded by children, be it Greta Thunberg saying “How dare you!” or pulling out school shooting survivors for a maudlin display. In his 2011 preface, Raspail says, in reference to those of us worried about the decline outlined in the book, not the omnicause, that while the immigration, decline, and replacement trends seem irreplaceable,

“It is also true that one cannot get out of bed every morning and poison the rest of the day and of one’s life by fixating over breakfast on the idea that everything is done for” [29.]

This is, in fact, what has been done to much of the population for decades now, by the media, teachers, activists, politicians, and globalist organizations. Nowhere is this more clear than with global warming, a cause in its infancy when the book was written but one which manages to encompass anything and cause many liberals to think the world is doomed- to such an extent that they don’t even fear confrontation with Russia and the risk of nuclear war! Since we’re all done for anyway, they would rather be “right” than alive, which is particularly bleak when one considers that they aren’t right either. Further, even if you do buy their global warming narrative [which I don’t] most of the things they want us to fear are easily manageable by human mitigation- for example, building some seawall, windmills, and lagoons around America’s coasts to deal with rising sea levels would not even be our most ambitious project for controlling water, compared to something like the Federal Columbia River Power System which built 31 hydro-power dams and prepared an enormous river system for being dammed.

Many of these people don’t want to have children because of “the world’s problems.” If they do, those children are raised to be nothing more than universal activists for the omnicause, fighting- or “raising awareness” of- the global polycrisis. They will have meaningless email jobs for the government or NGOs where they can bother other people in the office about paper waste, turning the lights off, racial microaggressions, or having a crucifix as a cubicle decoration, because of course being a socially and environmentally conscious antiracist nag is a greater contribution to society than just contributing to society in the way of any normal man who runs equipment for a living. The above of course only being those children who do well enough to work a pointless email job instead of becoming an antifa layabout with occasional barista work and full-time hatred of God, family, society, industry, and, most of all, white people.

Neither controlled by misery like in Orwell or pleasure like in Huxley, instead they are consumed by a vague sense of guilt about things far out of their power and shame at living in some amount of comfort in the civilization they were fortunate enough to inherit and should consider it their duty to protect. It is also, of course, no coincidence that every one of their causes leads to the loss of liberty, sovereignty, and economic well-being and are inevitably in the service of a global financial oligarchy. Meanwhile, they pretend the opposite is true, and that somehow protecting what you have is in service to the global financial oligarchy and not wanting endless migroids to drive down wages and raise housing costs and make schools worse and eat the swans at the park is just you being manipulated by the very oligarchy who endlessly encourage mass immigration!5 Raspail uses characters named Josiane and Marcel as working class whites passively observing the situation and trying to understand what is on the radio, representing the mass of faceless victims of the events in the story. Though Marcel is of vaguely French socialist sentiments [common among the working class] the narrator describes,

“But let a few truly serious crises erupt and there he was, secretly worried, wondering whether the crumbs that fell from the hands of the bosses and profiteers, decked out in their suede, weren’t better than no crumbs at all [122.]

In short:

Immigration brings together all of these things. The immigrant is a victim of racism- ignore the fact that he is choosing to come from a country where he is the majority! He is a victim of imperialism- ignore the fact that imperialism benefited a narrow class and the European working class got what they have from working, Marcel is still the oppressor! The immigrant is also fleeing global warming, of course caused by our cars and factories, which he hopes to own and work at in our country. He is only in poverty because you have food, ignore that we’re the ones who gave them better seeds. People only oppose mass immigration because of racism, or at best because of chauvinism for a corrupt culture not worth preserving. Ignore the fact that it hurts our own working class. Ignore the fact that they have not been able to fix their own country: they are still “elite human capital!” It is racist to fear crime, and anyway, their crime can be explained with our academic theories. This is why you read about migrant rapes in Europe and they send them to some pantsuit lady to talk about “alienation” and “cultural differences” instead of just bonking them on the head and throwing them in prison- which I assure you the migrants would both understand and respect. As Raspail writes of one of the only characters in the book who tries to stop the armada, [admittedly with somewhat gratuitous brutality],

“Be guilty of the most horrible crimes, rape and dismember little girls, beat old people to death with a hammer for a hundred francs, no matter, modern justice will come running to offer psychiatric aid and the excuse of a poorly made society. But no deeper explanation was sought for the appalling deed of Captain Notaras. He represented the white race and was found guilty of blind, racist hatred, full stop” [152.]

This sounds like it should be hyperbolic, but of course it is not, which is why the same “abolish the police” people in fact want ludicrously harsh sentences for random nonsense they feel involves racial inequality but don’t think criminals in the ghetto should be prosecuted for possessing illegal guns despite that they don’t believe in a right to gun ownership. Anarcho-tyranny, in short. Of course, further, when it is a random mass of migrants “they are all our family” and every day there is some immigrant, very often from the Indian sub-continent, trying to explain how they are the real best Americans because their entire life is dedicated to amoral grasping with no sense of duty, community, or loyalty whatsoever and isn’t that what America is all about? To this, the white liberal applauds, and wishes our country was full of such men instead of his- or more likely, her- own people. It really is all just as in the book, minus the fable of the single enormous armada, which serves as a vessel to explore these themes.

If you’ve read this far, please consider a paid subscription! It helps me keep these free and I am very poor, and I hear there is not a lot of money in saying positive things about this particular book.

What, then, of helping them at home, of making their countries better so they want to stay there? That seems to have only caused a population explosion of ever more people seeking to leave their countries and come to our countries. One of Raspail’s heroes, a Belgian Consul in India who tries to stop the flood, expresses how this has gone when speaking to a room full of the types of do-gooders leading to this apocalypse,

“You’ve given them everything they wanted - seeds, medical treatment, pharmaceuticals, technology - but now they want something much simpler: ‘Take my son. Take my daughter. Take us all, bring us back to your country’” [74.]

Shortly after this, the Consul speaks to his Indian counterpart, a man he has known many years and with whom he has a good working relationship. He finds that the man fully understands the situation and is gleeful about different waves of different kinds of his people going to Europe and ultimately destroying it- he claims that the second wave between a miserable first and third wave will be their best and most beautiful people! What consolation! This is presumably the one we are on in America now, with all these doctors and tech workers I keep hearing about. The Consul then lays out the situation in a way that brings up points I think we have all wondered about India, and which I must say in my observation appears more true of Hindus than any other Third Worlders,

“As always, you’ve found good philosophical reasons for your congenital negligence. You are an intelligent man. This country abounds in intelligent men. Yet you knew that already! You’ve given a perfect rundown! Famines, wars, floods, epidemics, exploding demography, superstition, the power of myth, the weight of number, it’s all there. No need for a computer to predict the future, though you have those, too…All these neatly described waves - you saw them coming! And what have you done about it? Nothing” [88.]

His Indian counter-part, who indeed fully understands the situation, then lays things out simply,

“You Westerners, you should have held fast to your steely contempt. Maybe then you could have done something? And now you’re dying of fear. Something irreversible is in the works, and if we see it through to the end, you will have fully deserved it and no will put up a fight” [89.]

All aid has done is weaken our resolve, breed their resentment, and introduce them to our weaknesses. The whole Western world is paying for it in spades. While endless agencies abound to “fix” the problem of global poverty, none of them accomplish much of anything good they simply cost money and cause problems. It is the novel’s President of France, a sane man not strong enough to fight the forces of history, who finally says something sensible about Third World poverty,

“Drinking a whisky when discussing the problems of the Third World is the only official response that’s ever seemed reasonable to me. These people hold forth at the UN and treat themselves to jet airplanes, coups d’état, wars, epidemics…but they reproduce like ants and, despite the deadliest famines, still somehow manage to proliferate in the most alarming way! So, I drink to their health!” [190.]

The Camp of the Saints is a deeply alarming novel, and not due to a race war narrative seen by simpler minds. It is alarming because of our own complacency and because it shows that we are so driven by shame at our past that we don’t want a future.

What is to be done? Public policy can’t easily fix this, though for Trump’s failings, his stricter immigration policies and willingness to be seen as cruel in enforcing such laws is a good start. Of course, after so many decades of government by liberal bureaucrats we are just as incompetent as the French military that collapses in the novel. Ending USAID was also a great step, though that was as involved in undermining the regimes of small former communist states as it ever was in feeding and medicating the Third World [food is, in fact, less of a factor that commonly imagined, because dry food commodities are extremely cheap in the modern world, and as in the novel, these people will keep procreating on a tiny amount of rice per day while forever looking at America and Europe.] Still, if one actually wants to help the Third World the reasonable way is through mutually beneficial investment, not by sending do-gooders around to show that we’re both wealthy and weak-minded. It has only built resentment.

If we are to have a future what is most important is that we learn to say “no” and to be strong in the face of miserable people trying to enter our countries. Instead of bombarding our children with the world’s misery or injustice at home and abroad, we need to keep distant charity and our fight against “injustice” segregated within our own lives, knowing that keeping our own affairs in order on a family and national level is what is actually best for everyone, most of all ourselves. Teach your kids charity, if you are so inclined, by helping your neighbors and your own community, and it is unlikely you will ever run out of things to do, even if you live in a nice area with little poverty. Emergency assistance from individuals or the government to distant crises is appropriate in extreme circumstances, but permanent charity and government aid is simply guaranteeing these countries forever eat at our table while hating themselves for doing so and hating us for owning the table.

Teach your kids to decline endless donations and demands that you never enjoy anything because someone, somewhere is miserable. Don’t let people judge public policies by the impact it may have on the most useless and wretched person they can possibly invent ad hoc in their senseless arguments against whatever might help the general public [the progressives have a truly incredible gift for inventing a hypothetical Most Disadvantaged Person to suit any scenario.] If we can not learn to responsibly manage our positions as the wealthy of the Earth, everyone else will only become more wretched as the means of production are sacrificed to the void of Third World poverty. As the saying goes, plant trees in whose shade you will never sit- perhaps your descendant will even turn one into a beautiful oak door. Don’t let a perverse sense of guilt and irrational pity cause you to let some miserable person chop down for firewood the oak tree or door that your ancestor left to you. Have pride in yourself, your children, your ancestors, your nation, and your culture. Remember that for what Raspail bills “the antiworld,” “Its only weapons are weakness, misery, the pity it inspires, and the symbolic value that has taken on public opinion” [163.] The tools to fight against those weapons are within us, if we have the fortitude to use them.

I’m going to end here with a personal story. Around 20 years ago, when I was still a young man, I was on a city bus in Olympia, Washington. The bus driver began arguing with a man I couldn’t see, your basic, “No, you can’t get on without money or a pass. I’m sorry, but you know this, I am not going to pick you up.” I assumed he was dealing with some big stinking homeless guy. When the bus moved, like the screen expanding for a visual gag in a sitcom6, I experienced one of the guiltiest internal laughs of my life: the indigent would-be passenger was a man in a wheelchair, and not just any man in a wheelchair, but a man with a degenerative disease like Stephen Hawking. Young, and with some idealism left, I was appalled at myself for finding the situation humorous, but more than anything couldn’t believe the callousness of the bus driver. The thing is, the bus driver is a man with a job and responsibilities: he is entrusted by the taxpayers to run the bus in a safe and lawful fashion, maintain order, and collect fares. He is not employed to be sympathetic to every cripple and to give them unauthorized rides7. What’s more, the disabled generally get free bus passes from the government or a charity, and further have access to Dial-A-Ride programs our society has deigned to spend taxpayer money on to help them. There was some reason only clear to the bus driver and the would-be passenger why he did not have a pass to ride the bus, but he obviously thought the bus driver would show cowardice in the face of weakness, which, in a great moral lesson to us all, he did not. I’m sure the bus driver felt like shit afterwards and perhaps even wanted to kill himself, leaving a cripple on the sidewalk like that just to do a good job at his job.

However, men like that bus driver are the backbone of America, and in a nation poisoned by toxic empathy towards global misery, may be our only hope.

Thank you for reading! The Wayward Rabbler is written by Brad Pearce. If you enjoyed this content please subscribe and share. My main articles are free but paid subscriptions help me a huge amount. I also have a tip jar at Ko-Fi. My Facebook page is The Wayward Rabbler. You can see my shitposting and serious commentary on Twitter @WaywardRabbler.

I received a postcard from Samaratin’s Purse in the mail while writing this and it was telling me how to donate a big chunk of your IRA to them! This of course, instead of holding your money so an heir gets it. In their defense, the photograph had smiling Bolivian adults, not starving Indian children.

I don’t think the author anticipated the success of Norman Borlaug’s “Green Revolution” in ending famine, which was just beginning to bear fruit at the time of publication, and which presumably also spared us a certain amount of suffering.

This is the Penguin Classics Deluxe Edition.

My state does not have any sort of container deposit law, so collecting aluminum cans for scrap prices produces only a truly abysmal amount of money.

The last time I heard something this stupid outside of on this topic was when people claimed wanting to end lockdowns was some sort of oligarch plot because of a nonsense reddit thread despite every corporation supporting them. God, I wonder if Raspail, who lived to be a very old man, until 2020, was aware of reddit’s consequences for society. He would have taken a dim view.

There is a specific rhetorical term for this, but I hated my rhetoric teacher and didn’t memorize the vocabulary. He used Arrested Development as an example in class. If you know what this is called, please leave a comment.

It should be noted public services and public life have totally gone to shit in that whole region in the last 20 years, but in the mid-2000’s the buses were still clean, orderly, and on time.

My sense is that the Third World do-gooderism has really declined in recent years, being replaced by the demand to allow in infinite migrants.

There are more financial incentives to bring in cheap labour, they vote for the left and it creates plenty of jobs for left wingers that don’t involve international travel. Going to Africa to hand out gibs probably seemed exciting to young boomers, but doesn’t appeal as much in an aging and feminized society.

Good stuff, thanks for sharing.