The UAE's Neo-Venetian Empire

Meet Africa's New Suzerain and the World's Next Great Power

“When they felt their numbers were sufficient to form a body politic, they closed the avenue to participation to all those who might come there to live in the future…It was possible for this system to arise and maintain itself without any disturbance, because when it was born, whoever then lived in Venice was made part of the government, so that no one could complain; those who later came there to live found the government fixed and limited, but they had no motive or opportunity to cause a disturbance. There was no motive because nothing of theirs had been taken away; there was no opportunity because those who ruled kept them in check and did not use them in matters through which they might acquire authority.”

- Machiavelli [Discourses, I.6]

“A country that has no mines of its own must undoubtedly draw its gold and silver from foreign countries in the same manner as one that has no vineyards of its own must draw its wines…a country which has the wherewithal to buy gold and silver will never be in want of those metals.”

- Adam Smith [The Wealth of Nations, IV.1]

Table of Contents:

Introduction: Like a Snake Around Africa

Background: From Oasis Villages to Mega Towers

Shipping: Every Port in a Storm

Mining: All That Glitters is Gold

Conclusion: The Crucial States

Introduction: Like a Snake Around Africa

The small Persian Gulf state of the United Arab Emirates has experienced a meteoric rise in fortunes over the past 25 years, driven by invested oil revenue and a large foreign worker class lacking civil rights. The UAE’s newfound prominence is surely the greatest rise of any state of the 21st century. The descendants of desert Sheikhs from 100 years ago are now the heads of vast business empires which tie the economic interests of the royal families in this federation of absolute monarchies to the political ambitions of the federal state. It is not an exaggeration to say that the Emiratis have built up a neo-Venetian Empire, right down to their interests in Indian Ocean trade, their famous love of land reclamation, and a political structure whereby the great majority of their population does not, and never will, hold any form of citizenship. The average person knows of Dubai as a retreat for the wealthy and a great center of commerce, but though the United States has labeled the Emirates as a “Major Defense Partner” and it docks the most American ships outside of the United States, the global power of this collection of fiefdoms- where there is little separation between economy and state- is not well understood.

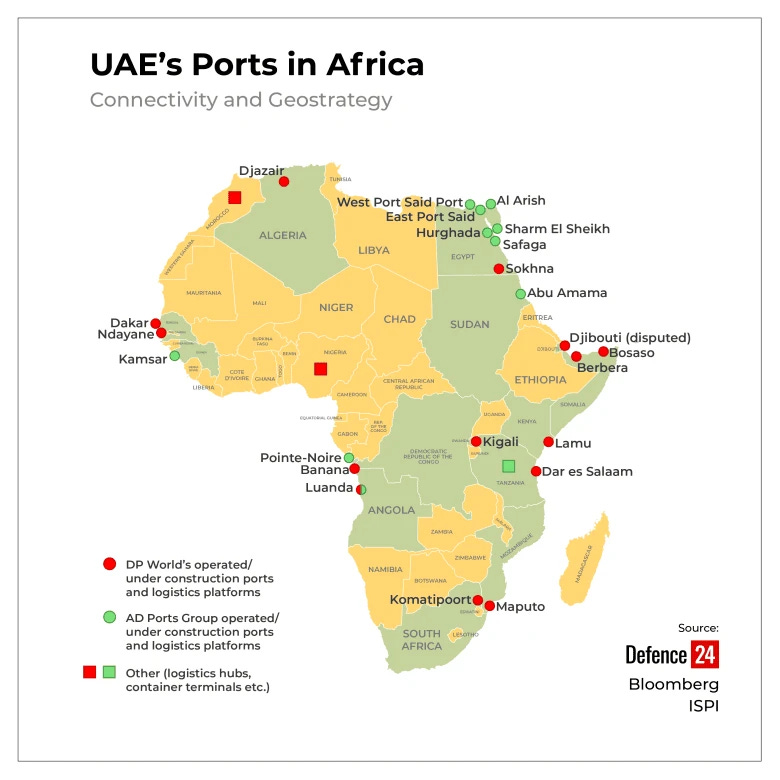

Though the hands of the Emiratis reach across the world- for example Dubai’s DP World controls 10% of global shipping and and Abu Dhabi’s ADQ have bought 45% of the Louis Dreyfus company1, one of the world’s largest agricultural commodities corporations- it is in Africa where Emirati and influence is the most pronounced. The UAE, and to a lesser extent its partners in the Gulf Cooperation Council, have been buying up African resources at a shocking rate, with the UAE, which has an economy perhaps 1/60th the size of the United States’, becoming the largest foreign investor in Africa in 2024. Almost anywhere you go in Africa you can find the hand of the Emiratis: from the Busaso air base in the autonomous Somali region of Puntland, right next to the tip of the Horn, to a new port being built just south of Dakar, the Westernmost city in the “Old World,” to a major “dry port” in South Africa, and to the $35 billion they have paid Egypt to develop the city of Ras al Hekma on a small Mediterranean peninsula, they have crossed the length and breadth of Africa. The United Arab Emirates has begun wrapping itself around the continent like a snake, covering its coast with ports where it can sell goods and extract wealth. They have raked into the continent’s mines, at times nearly buying national mining companies outright. They have filled Africa, especially Egypt and Sudan, with huge center-pivot agriculture plots to export food directly to their desert home. Their cities sparkle in gold extracted from countless artisanal mines which often entirely avoid regulation in tax-starved states. They have created a network of secessionist counter-revolutionary paramilitaries fighting in some of the world’s most brutal conflicts. Africa’s famously corrupt and complacent elites don’t seem to stand a chance when put against the wealth, discretion, flexibility, and crass amorality of the Emiratis.

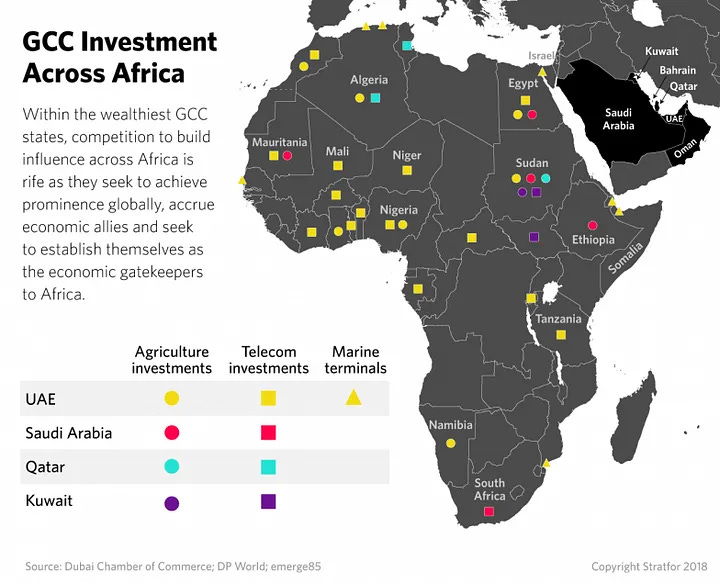

The major powers have historically pursued different primary strategies on the African continent, though all ultimately grab money or influence where they can. The French are on the outs, but long maintained economic control and political influence of Francafrique by any means necessary, including near-constant military interventions. The Americans followed France in their former empire, but outside of it have generally overwhelmed the continent with “aid” money, “NGOs” from the State Blob, military training, and hollow professions about human rights. The Russians profit from flooding the continent with cheap weapons with little regard how they will be used, which makes them popular with hotheads and tinpot dictatorships but less so with the more experienced and responsible types. The Chinese favor large infrastructure projects, where Chinese citizens holding all of the high-paying positions and African workers serving as a poorly treated serf class. With the Emiratis and their Gulf Cooperation Council [GCC] partners, it is almost all capital, gaining enormous concessions and buying private and state companies up and down the chain, gaining a slice of all economic activity on the continent. It’s true that Africa is capital starved, that its ports need better infrastructure, its farms better inputs, and its mines bigger equipment, but what will be left for Africans if the growth in power of this cynical gang of autocrats is not arrested and the continent’s veins are again cut open and let to flow to the Persian Gulf? It is already happening.

Background: From Oasis Villages to Mega Towers

The area that is now the United Arab Emirates has been inhabited by humans since pre-history, but despite its central location was always something of a backwater and rarely entered the historical record besides as a spot at the edge of empires. Its neighbor, Oman, was the one which in the past conducted a lucrative trade along the Swahili Coast and across the Indian Ocean, though they fell under the control of the Portuguese for more than 100 years at the beginning of the Age of Exploration. Near the beginning of the 18th century, the Sultanate of Oman became wealthy and powerful, particularly from the slave trade based in Zanzibar but also the trade in other important commodities, notably ivory and gold. The dynasty ultimately split in the mid-19th century with houses based in Muscat and Zanzibar, but at various times the Omani royal family were suzerain over large sections of East Africa2 as well as several areas within the Persian Gulf, including the modern UAE. Most notable for our purposes here is that this is not the first time Gulf monarchs have grown fabulously wealthy from the exploitation of Africa.

Omani fortunes began to change when British influence grew throughout the region. They initially allied with Oman but their international prohibition of the slave trade was profoundly harmful to Omani interests. In keeping with their practice of empowering local rulers, instead of overthrowing the Sultan of Zanzibar the British “leased” key territories from him, such as Mombasa, Kenya. Some of these areas remained nominal possessions of the Sultan until the era of independence in the 1960’s. Though he remained one of the wealthiest and most respected “traditional” rulers in Africa, his potency in international matters was entirely gone, and ultimately Zanzibar merged with Tanganyika to from Tanzania while Oman became the humble Sultanate it is today.

Early in the era of British supremacy, what are now the Emirates were impoverished fiefdoms. The ruling families of both Abu Dhabi and Dubai, the two most important emirates, had arisen from a tribe centered on the Liwa Oasis in Abu Dhabi. Besides date agriculture at Liwa and a few other scattered oases, the main economic products of the region were harvesting pearls, fishing, and, as one does, raiding; the pearl industry became unprofitable when the modern technique for culturing pearls became widespread. The British came to call the region “the Pirate Coast,” though some in the Emirates deny the extent to which piracy was an issue. Instead, they claim that the British simply used this as a pretext to take control, which is fairly classic British Empire; there is no need to further adjudicate the matter here. Ultimately, after a series of threats, blockades, and military actions, the British beat truces out of the potentates along the coast one after the other, ending piracy and protecting the interests of the British East India Company. British influence became greater over time, and they also banned the slave trade and gained exclusive control over their foreign relations. This region became known by the British as the “Trucial States” or “Trucial Coast”, which is an uncommon adjective form of “truce.” Bahrain and later Qater were also Trucial States, but did not reach an agreement with the others at the negotiations which founded the UAE.

This collection of informal protectorates remained of little significance to the British besides to guard commerce from the Persian Gulf to India, until the invention of the airplane, at which point they served as a convenient stopover in the early days of aviation. In the 1950’s a Trucial States Council was formed, though it was initially merely a discussion forum between Emirs overseen by the British Agent. Most importantly, in the 1960’s, after decades of exploration, viable oil wells were discovered in Abu Dhabi and Dubai, setting them on the path they are on today. When the British began withdrawing from their Empire “East of the Suez,” the Emirates entered into negotiations to form their own state, and 6 of the Emirates formed the United Arab Emirates in 1971, with a 7th joining the next year. By custom, the Emir of Abu Dhabi, the wealthiest and most populous emirate containing the capital city and the majority of the country’s territory, is elected President of the UAE by the Federal Supreme Council, which consists of the 7 Emirs. The President then appoints the Emir of Dubai, the second most populous emirate and the country’s commercial capital, as the Prime Minister and Vice President. The current Emir of Abu Dhabi and President of the UAE is Mohamed bin Zayed al Nahyan [commonly called MbZ,] who has held that position since his brother’s death 2022, though he had been an informal regent of both positions since his brother’s stroke in 2014. Since 2006, the Emir of Dubai, Vice President, and Prime Minister has been Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, now one of the world’s wealthiest property developers and seemingly the mind behind the aggressive expansion of Emirati business interests.

The remaining emirates range from Sharjah, a prosperous emirate neighboring Dubai that has become the Emirates’ center of high culture under its scholarly and enlightened ruler Sultan bin Muhammed al-Qasimi, down to Umm al Quwain, a territory of 70,000 people which has a GDP per capita (PPP) roughly equal to Thailand, and which looks like it belongs in a middle income area of Africa, though such places are rarely so thoroughly street mapped by Google3; I can only imagine how that Emir is treated at the Council meetings. Most of what follows is about the Emirates of Abu Dhabi and Dubai, both because they control the Federal Government and because it is their “private” enterprises which are responsible for much of what it is said “the United Arab Emirates” does, often moreso than the federal government itself [for one visible example, Emirate Air is owned by Dubai, not the UAE.]

The form of government in the United Arab Emirates, a federation that is functionally an elective monarchy, was once common, though I believe it is the only one in the modern world. Each emirate has almost complete internal autonomy outside of defense matters and the country being an internal free trade zone, though there is a federal supreme court covering 5 of the 7 emirates who agreed to its jurisdiction. The Constitution of the United Arab Emirates claims they are moving towards democracy and the other various modern platitudes, but it isn’t much of a thing. In reality each emirate is its own absolute monarchy, though I don’t believe there is any great prohibition on any of them choosing to liberalize. There are theoretically various human rights such as being innocent until proven guilty, but they have little hesitation about doing whatever they want if someone causes them problems [that said, in general, they want to be taken seriously as modern and civilized countries, and as such don’t find public brutality useful.] The professions of liberality notwithstanding, the system is similar to what one would generally call “feudalism”, though that is itself an anachronistic term invented later to describe a prior system some say never existed in the described form. Regardless, the big innovation is not insincere professions of human rights, it is that historically nobles weren’t generally allowed [by law, custom, or both] to take part in commerce, which made them unable to compete with the capitalists, whereas the Emirs are state capitalists and [besides the one] are remarkably successful.

Though oil wealth had been coming in since the 1960’s, the Emirates were not well known until around the early 2000’s. I was a teenager and admit had imperfect geographic knowledge, but don’t believe I heard of Dubai until the mid-2000’s when it was rapidly filling with ever more foreigners and getting involved in ever more ambitious projects, such as building the world’s largest skyscraper and dredging up island formations on which to build luxury properties. Little had been considered about fully diversifying the economy, though the Dubai business empire was increasing. They didn’t heed the “Sky Scraper Index,” and despite that it should have been obvious building the world’s tallest tower meant a crash was coming, Dubai was seemingly caught unaware by the housing bubble bursting. The reduced value of real estate and lower oil prices nearly drove Dubai to bankruptcy, and 2 of the 3 major fake island formations were never finished, even to this day, while Abu Dhabi bailed out the building of the Burj Khalifa skyscraper, with then-President Khalifa’s name being given to the project.

Dubai, and the emirates generally, managed to survive and keep growing, getting involved in ever more businesses. Dubai is now one of the world’s most famous cities and a top destination for foreign workers and wealthy expatriates. In both Dubai and Abu Dhabi there are many advanced industries, an enormous trade volume, and endless construction projects. It is something like the crossroads of the world. It is a great place to live if you are rich and like city life. A well-funded government keeps the cities safe and orderly with very low crime and excellent public services. Despite frequent reports of bad conditions, it must not be that bad for lower skill workers, as, besides women who are trafficked there through force and fraud and the like, enough people have been working there for long enough that the average Filipino or Bangladeshi laborer must show up knowing something of the conditions and deciding they are worth it. There has never been any consideration of allowing naturalization or giving the foreign majority political rights. In fact, the natives don’t have political rights either, but do get important and high paying positions for the government and incredibly generous state assistance of all kinds. The UAE now has what has been called “the world’s most powerful passport” which gets you into 90% of countries visa free. There are federal personal taxes on citizens or residents in the country.

The nature of the situation is the most readily shown with a “social contract” meme, which I should explain to less “online” readers. In short, this meme format, originating with France, is based on the premise that a 30 year old named Nicolas is a worker who has his face in his hands in exasperation because the government redistributes his wealth to everyone else. Of the countless which have been made, it is only in the UAE and Singapore where it is the average citizen who is shown to benefit, with it instead being the government’s resources and the work of foreigners benefiting him:

The other states in the Gulf Cooperation Council pursue largely the same sorts of policies as the UAE, using their remaining oil wealth to diversify their economies, focusing on some degree of food self-sufficiency [an impossible goal, but reducing the impact of price swings is possible], having out-sized influence, and the like. However, in most areas they pursue these policies with less success. There are two main exceptions to the relative uniformity of the GCC state economic policies. The first is the that the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is a proper sized country and actually has a large body of citizens it must think about keeping productively occupied, in stark contrast to somewhere like the UAE, which is 88% foreigners, enough to more or less occupy the citizenry in managing them. The second exception in the GCC is Oman, which though it is trying to diversify its economy, perhaps having already once been a great power and recognizing the vagaries of fortune, seems to eschew the ambition and glamour of its partners and be happy to be a pleasant and friendly small country that prefers peace to conflict.4

What impresses many so much about the UAE is that these cities are extremely nice, wealthy, orderly, and safe. While the UAE is a wonderful place to live if you are a citizen or have money [or are the mistress of either, I suppose] many feel that it requires a degree of disconnecting yourself from the obvious injustice in this greatly unequal society. This is not just the amount of the wealth that comes from exploiting Africa, but also perhaps 70% of the population are some variety of an underclass. It’s also that the royals are themselves often like the villains in a 1970’s cartoon, nearly literally. You can easily imagine an episode of Scooby Doo where someone wants to sell a mine because a monster is running around but then it is just some oil billionaire in a keffiyeh who wants to buy the mine at a discount- this is pretty similar to how they function in Africa. Speaking of cartoonishly evil, the Emir of Dubai was also once sued for keeping child slaves from the third world to use as camel jockeys [Dubai did not ban the practice of child jockeys until 2005 and did pay some damages to children from other countries who were abused in this way, but I don’t think it was every fully determined if the children were properly “slaves” and if the Emir himself was guilty.] There are also credible claims that he has at times imprisoned wives and daughters, with one wife, Princess Haya of Jordan, winning an incredible $720 million divorce settlement in international court as well as a no contact order for herself and her children, though this is generally in line with the control a wealthy man has over the women in his household in this region, and I think it sounds crazier to us than it does to them.

It doesn’t sound unreasonable to say you shouldn’t enjoy living somewhere like Dubai because of the unfairness and lack of rights in society, but I do think it is probably unreasonable. Realistically, you have substantially less need of freedom and personal justice when the government is doing a good job at keeping you fed and providing services. It also must be said that cities like LA or London are full of a foreign underclass without proper political rights, are in countries that pursue evil and destructive foreign policies, and have brutal and criminal elites, and yet despite loading you down with taxes those cities are shitholes instead of being nice. Many countries are oppressive and highly unequal and still just constantly drain your money while failing to keep you safe or keep the streets clean or make the trains run on time. It’s easy to see how someone who is used to living in a dysfunctional country, moving to the UAE, if you can afford it, would feel like leaving a lot of problems behind. On a balance, unless you wish to withdraw from the world like a hermit, if you can afford it and want to, you may as well enjoy life in the Emirates instead of letting the world’s injustices get you down, though that is just my perspective.

One way or another, the UAE continues to thrive, feeling almost like something of a new model of state, if not a replicable one. However, despite its “middle power” status it increasingly looks like one of the most important countries on Earth. Much of the UAE’s newfound wealth and power comes from Africa: from its ports and trade, from its grain, and from its mines, and for reasons that are somewhat less clear, from its wars.

Shipping: Every Port in a Storm

Dubai Ports International was founded in 1999 and later merged with the Dubai Port Authority to form DP World in 2005. The company has followed a strategy of aggressive growth and acquisitions, reaching $20 billion in revenues in 2024. According to their website, DP World has over 100,000 employees of over 160 nationalities, and handles more than 10% of global trade. The company’s rapidly expanding freight forwarding service covers more than 90% of global trade; it doesn’t appear this is exclusive [in the sense of each cargo being covered by only one service] but regardless it provides incredible and specific insights into all global trade. It also owns a variety of businesses up and down the value chain. DP World expanded rapidly from the start, specifically when it bought the British P&O shipping giant in 2006, then the fourth largest operator of ports in the world. You may remember the controversy this caused at the time, as the deal would have given the DP World control over 6 major US ports; the deal was supported by President Bush, but due to it being the height of the War on Terror there were serious public concerns about a Muslim Middle Eastern country controlling our ports, if I recall correctly concerns that were ginned up by talk radio. What is perhaps most notable about this however is that at the time, just under 20 years ago, the United Arab Emirates was still a somewhat obscure country and much of the confusion was about how they ended up in a position to manage 6 major US ports.

Currently, DP World operates over 60 ports and terminals all over the world, though their ownership percentage in those operations varies, and they are commonly under joint ownership with the port authority of the host municipality. A search for “DP World” on the Port Technology industry news sites demonstrates the enormous breadth of DP World’s influence in the US economy, or as the company itself somewhat ominously describes it, “we continue to expand our reach deeper into the global supply chain.” Dubai’s Jebel Ali port is the world’s largest man-made harbor with 77 berths and is the busiest port in the Middle East. A 2024 article from the shipping analytics company Xenata claims that Abu Jebel handles 4.6% of the world’s ocean containerized freight; it is the 11th busiest port in the world, and it must be noted that the others, excepting Singapore, open up to areas with enormous populations, whereas Dubai is but one of two major ports in the 10 million population UAE and is dealing with so much freight because they built the port and aggressively positioned themselves as one of the world’s major trade cities. From managing a small backwater port trading oil for grain in 1972, Dubai World has grown into a shipping conglomerate with enormous power over international trade.

DP World is just one of the two major shipping firms in the United Arab Emirates. Being the private property of the Sheikhs have made these businesses different from most examples of state capitalism as there is a direct, legal, personal profit motive and they are not regulated by any legislature. Abu Dhabi was later getting into the international business game, having a greater landmass and larger oil reserves than Dubai, but it has also become a serious player. This is particularly true since the Abu Dhabi sovereign wealth fund was rebranded in in 2020 as ADQ, incorporating many of the companies performing vital state functions under one umbrella and expanding aggressively. Their interests remain most of all in Abu Dhabi’s own port, but a search on the same Port Technology website shows them investing in trade terminals in places as diverse as Bangladesh and Tbilisi, as well as big investments in Congo (Brazzaville) and Angola. However, their biggest foreign investments are in Egypt and its Suez Canal, giving them substantial control over one of the world’s most important shipping lanes. Abu Dhabi’s website describes just some of its investments- all since the above map was published- as follows,

“Since 2022, AD Ports Group has invested significantly in Egypt, acquiring Transmar, a regional shipping company, TCI, a port operator and stevedoring company, and in 2024, Safina B.V., a provider of maritime agency and cargo services. AD Ports Group has also secured long-term concessions to develop and operate three cruise terminals at the Red Sea ports of Safaga, Hurghada, and Sharm El Sheikh. In addition, AD Ports Group has initialled agreements for the right to develop and operate a cruise terminal and a Ro-Ro terminal in Ain Sokhna.”

This is a good example of the investment model of the Emirates, in that they will come into a region and rapidly buy up multiple key businesses within an industry as well as getting concessions from the government. This also brings up not one, but two, interesting points about the way the country’s foreign policy interacts with the business interests of the two main Emirates and further how they have made themselves so essential they seem to be on all sides of everything. Firstly, in all of the talk about the Houthis attacking cargo ships and slowing Red Sea shipping, I never saw it mentioned that their enemies in the Emirates were deeply invested in the Red Sea and Suez Canal, and that as such they were harmed along with Israel. Further, Egypt is a key supporter of the Sudanese Armed Forces, with which is has longstanding ties, and it doesn’t seem that the UAE’s support for the Rapid Support Forces in Sudan has damaged its ability to profit off of Egyptian trade. However, in another indication of how their business interests protect their foreign policy, in 2024 ADQ signed a deal to invest $150 billion into a 130 million square meter concession to create an Emirates-style city in the the resort area of Ras al Hekma on Egypt’s Mediterranean Coast. $24 billion of this money is direct payments to Egypt’s government, while another another $11 billion is in the form of a deposit into Egypt’s central bank. This is the largest foreign investment in Egypt’s history, and big enough that the infusion of forex reduced consumer prices in the country of more than 100 million people which is in the midst of a financial crisis and has been struggling to raise cash for imports. What this shows is that with access to enormous capital and the ability to act flexibly, if they move at the right time the Emirates can buy off even a larger state and do so even when they have major conflicting interests.

Emirati infrastructure investments are transforming Africa and turning the UAE into a world power. While other Gulf States are also in this new scramble for Africa, it is the Emirates who are leading the way, and they are the only ones in the port business. Gulf money now impacts how hundreds of millions of Africans communicate, buy goods, and earn money to buy those goods. Telecommunications, railroads, and trucking are all infrastructure industries in which there have been enormous investments, all of which support the competing logistics giants of DP World and ADQ.

Unfortunately the most recent good map I can find of such investments is the above from 2018, and the locations have drastically increased: in 2023 the GCC countries poured $53 billion into African projects, compared with $10 billion from the United States in the same period. Roughly half of GCC money going into Africa is from the UAE, now by itself the world’s largest investor in Africa.

Emirati investments in Africa are too diverse to list- in fact I realized I didn’t find a place for talking about their $250 million deal to manage the port in Tanzania’s capital of Dar es Salaam anywhere in this article- but South Africa provides a good case study, particularly as it has the most developed economy on the continent. In 2019 DP World opened a “dry port” at Komatipoort on the border with Mozambique. Having managed Mozambique’s Maputo port since 2006, this means containerized ocean cargo can be moved inland by train or truck with DP World dealing with the customs regimes of both Mozambique and South Africa. Africa does, once again, have a need of such services. One of the continent’s major problems post-independence was that most logistics were ran out of the former imperial powers, making the new states still largely colonies that primarily only traded with the “home” country, such as America pre-independence. Into at least the 1980’s, international phone calls between African countries commonly routed through London or Paris [you can be sure the French listened in, the British have been relatively more hands off, so perhaps they did not.] That the UAE has overcame a trade barrier with this system is good, but their aggressive expansion only reinforces concerns about their increasing influence.

After opening their dry port in 2019, DP World bought Imperial Logistics, the leading logistics company in South Africa, with a major international branch headquartered in Germany, for a reported $890 million. Imperial has 25,000 employees and has a vast operating network across Africa, Asia, and Europe.

Upon purchasing Imperial, DP World also expanded that company which already had a large portfolio including things such as pharmaceutical distribution in Namibia, a mercantile company in Ghana, and an import company specializing in Asian markets. Most notably, Imperial bought a controlling stake in Nigeria’s AMFCG Distribution a 130 year old company, dating back to before the British unified multiple territories to create modern Nigeria. On top of all of this, in 2024, DP World got the contract from British Petroleum South Africa to distribute fuel in many of the country’s most important markets, which means that not only does DP World ship the goods to Mozambique and then transport them into South Africa and to their final destinations, it even delivers the gas that fuels the trucks doing it. Huge swathes of inland southern Africa are now wholly reliant on DP World to export the goods they rely on to make a living while they deliver most imported products and have specialized interests in key sectors such as pharmaceuticals. On top of all of that, not to be left out, in 2024 Abu Dhabi’s International Resource Holding, a recently consolidated sovereign wealth fund, signed a deal with South Africa’s Public Investment Corporation to, among other things, expand the rail freight network, meaning that if containers leave those trucks, they may still remain in Emirati hands on the railroads.

DP World has long been involved in Algeria, where the Djazair Terminal in Algiers has been under its management since 2008, one of two ports where it has concessions in the country. Between 2009 and 2021 DP World invested more than $114 million in the terminal, doubling its capacity; this terminal also gives DP World access to the Trans-Saharan Highway as well as rest of Algeria. Another major terminal near the airport outside of Kigali in Rwanda, where DP World built the country’s first major cold storage facility in 2020. By the standards of DP World, the Kigali terminal is a fairly modest facility, but this tour to business owners give a good example of the way they are into delivering every product into key regions of Africa.

What is more, and this indicative of the experience of trying to unravel Emirati business interests, it turns out this Prime Trucking LTD whose trucks you see on the video is part of what is called the Suhara Group, a major African logistics company headquartered in the Jebel Ali Free Zone in Dubai. It appears this company was founded by a Tanzanian [seemingly of Omani extraction, from when they owned Zanzibar] but they acquired a Dubai-based company and moved their headquarters there to partner with DP World and use it as their main logistics hub, demonstrating the extent to which Dubai is becoming the economic and trade capital of East Africa.

Perhaps DP World’s most ambitious current project is in Senegal, a country where oil production for export just came online last year and liquefied natural gas is expected to be ready imminently. Senegal is one of the most stable countries in West Africa, but has been plagued for decades by gridlock in the main economic zone, which is on a tightly packed peninsula containing the westernmost point in Afro-Eurasia. DP World has managed the aging and inadequate Dakar Port since 2009, increasing its capacity from 300,000 TEUs to 900,000 TEUs5 with an investment of $300 million in that time, but regardless it is time for a new port and a nearby economic zone. In 2020 DP World got the contract to build a $1.2 billion new port just south of Dakar at Ndyane in partnership with the Dakar Port Authority. The new port is near an ocean oil platform as well as the country’s new airport that was built by the Saudi Binladin Group, replacing the old one that was crammed onto the peninsula and could not expand. Though the new port will “only” have 1/3rd higher capacity than the Dakar port, it will give truckers easy access to both the open road and the airport as well as giving Senegal the extra capacity to take advantage of its convenient location as a transshipment point between Africa, South America, and Europe [the Dakar Port, which is very convenient for the trade of the city itself, will continue to function.] This project is likely to turn Dakar into the most important trade hub on Africa’s Atlantic Coast.

Senegal has fairly high state capacity by African standards but there are still big questions about making this new deal when they knew their own oil and gas would be coming online. They have surrendered control of their trade capacity to Dubai when they didn’t have to, and it seems they could have instead made any number of other decisions while planning for incoming wealth. It doesn’t seem particularly different than French corporations controlling most such functions in their former empire for decades after independence [and in many cases, they still do.] Perhaps more importantly while it sounds good for Senegal to have a major trade hub for West Africa, the thing about that is it acts as a giant funnel for Dubai to suck the wealth out of the region and monopolize the transit of essential goods across West Africa, a large and notoriously unstable region.

Closer to home, DP World ports have ran into more difficulty in what used to be called the Somalilands. They encountered a rare but major setback in Djibouti when after managing the port for years in 2017 the country tried to kick them out saying that it was violating their “sovereignty.” This is on its face absurd as Djibouti is a miserable little country whose President for Life has always survived on renting the nation’s sovereignty to all bidders, which is why it currently has both US and Chinese naval bases [much to the chagrin of the US] as well as bases of several other smaller powers. DP World sued them in an international court in London- the contract specified that it would be under English law- and the international court ultimately determined that Djibouti owed $385 million for breach of contract, and that they could sue again if the contract was transferred to any other operator. Djibouti then gave a 25% interest in the port to a Chinese interest, in what was widely considered to be a surreptitious way to pay off a debt. DP World also sued them in a court in Hong Kong and again won, with Djibouti’s owed damages nearing $700 million by 2022, though they’ve shown no indication they intend to pay. Broader concerns about the UAE’s power notwithstanding, it is an obvious breach of contract for spurious reasons and that is what courts found.

Shortly before trouble started in Djibouti, DP World signed an agreement to modernize the port in Berbera in the unrecognized state of Somaliland. DP World valued the 30 year concession at $442 million. They have turned Berbera into one of the nicest ports in northeast Africa. DP World’s presence has been a great boon to Somaliland, which struggled to make trade agreements due to its unrecognized status, but with access to goods coming in and out of Dubai it has access to the world. This upset the government of Somalia in Mogadishu, which jealously holds onto its claim of Somaliland, despite that it has not controlled any of it since 1991 and has no ability to get it back. DP World was banned from operating within Somalia. Negotiations for Ethiopia to invest in the port and create an export terminal reducing its dependency on Djibouti, which previously handled 95% of its sea trade went on for years, and were what ultimately led to Djibouti seizing DP World’s terminal in its port. The countries have gone back and forth over a deal for years, much to the chagrin of other regional stakeholders, but the plan to supply Ethiopia through Berbera at a large scale has never quite materialized. Regardless, Somaliland has become an important regional partner for the Emirates, and DP World continues to improve the port, including the addition of an edible oil terminal, which may sound like a random thing to make a big deal out of, but for many Africans who primarily produce their own subsistence, cooking oil is a main cash expense and there is a high demand on the continent. What’s more, Abu Dhabi’s main holding company owns a major vegetable oil company, a business Dubai is also in, so it seems likely it will be the Emiratis who supply the oil and build the bottling plant, another example of how once Emirati business interests have a tendency of expanding to include everything.

Meanwhile, ignoring the Mogadishu government, DP World also made an agreement with Puntland, the self-declared autonomous region of Somalia, to expand its Bosaso port. This is said to be a $366 million deal, giving the port the ability to handle containers for the first time, meaning it can be visited by modern ships. This is an indication of the Emiratis practical and “cash is king” strategy, as Puntland is in a long-running border dispute with Somaliland and this was also opposed by the nominal central government in Mogadishu, but DP World still came in and made a deal worth hundreds of thousands of dollars.

All of the above still misses endless other Emirati projects in Africa. Port investments in Africa are necessary to support Africa’s rapidly growing population- and hopefully improve quality of life- but for a continent that has been colonized before the amount of control that only two foreign sovereign wealth funds are taking over all trade is a matter of serious concern. This sort of thing is quite similar to how the Portuguese opened the world up to colonization 500 years ago. There is no sign that the Emiratis are stopping, and logistics is only one of their businesses in Africa.

Adam Smith has a quote about the growth of colonies which is somewhat curious to compared to the Emirati strategy. He wrote,

“To found a great empire for the sole purpose of raising up a people of customers may at first sight appear a project fit only for a nation of shopkeepers. It is however, a project altogether unfit for a nation of shopkeepers, but extremely for for a nation whose government is influenced by shopkeepers. Such statesman, and such statesman only, are capable of fancying that they will find some advantage in employing the blood and treasure of their fellow-citizens to found and maintain such an empire” - The Wealth of Nations [IV.VII.2]

While the government of a company of merchants such as the East India Company was well known to Smith- he even called it the worst form of government- the direct combination of state and economic power that the United Arab Emirates represents was most likely a thus far unknown thing in the world. Indeed, primarily two merchants, the emirs of Dubai and Abu Dhabi, control the entire country and it currently seems as if few stand a chance against princes with vast capital who face no governmental restraints and who genuinely are the state.

Land: Graining the Desert

The countries of the Gulf Cooperation Council have been making huge purchases of farmland and other agricultural interests around the world for decades, but particularly in Africa. The GCC countries want a higher degree of food security, feeling they are too dependent on imports. Africa is said to have the majority of the world’s unused agricultural land, and that land which is used is generally greatly starved of capital- irrigation projects, fertilizer, quality seed, and equipment. Foreign investment may seem like a match made in heaven, but the reality is much different. Firstly, it isn’t obvious how this improves Gulf food security in the national security sense, though it does make them more resistant to price fluctuations [these least capital starved countries on Earth.] For Africa’s part, once they buy this land, most of all in Egypt and Sudan, the country gets money from the initial sale, but then neither the food nor the profit go into their economy besides whatever it adds to their tax base and whichever Africans may be employed on the farms, both of which are probably minimal [industrial farms employ very few people for their size, and half of those workers are probably South Asian.] The reality is that the African countries have sold [or long-term leased] their land for short-term profits while their soil and water gets depleted and their environment gets degraded. The Gulf states get all of the grain and the profit. Of course, all of this is done for the benefit of those countries’ elites with little input from the public. Beyond farmland, the Emiratis are buying vast swathes of forest to take part in the Paris Accords’ “carbon credits” scheme, which it seems that everyone but a narrow class of liberal internationalists recognizes as an obvious scam. There is a land rush for Africa, and the continent’s cash starved governments and greedy elites are for the most part more than happy to sell the soil under their feet for Gulf money.

The Gulf states have long been concerned about their reliance on imported grain. Saudi Arabia in fact rapidly became a wheat exporter several decades ago and continued to export wheat until about a decade ago, when their “fossil water” mined from deep beneath the desert began to run out and they started to question the logic of growing their own grain instead of importing it and shut down the program. The United Arab Emirates, in particularly Abu Dhabi which has two major oases, has an impressive agriculture sector given its limitations. Dates were traditionally the major part of the economy at the Liwa Oasis where the tribe of the ruling houses of Dubai and Abu Dhabi got their start. Beyond that, there is a decent amount of water near the Omani border. These countries have been innovators in making the most of what they have, and while they do grow grain and fodder at certain locations, Abu Dhabi agriculture production is primarily focused on tree crops, high value produce such as tomatoes, cucumbers, and berries. The Emirates have also been leaders in indoor vertical agriculture, which is particularly adapted to Dubai which is a high-tech extreme urban environment. All of these things are good for a diversified economy, and vertical agriculture is a great way to get fresh salad greens in a large city, but these are not long term solutions to producing a population’s staple crops from which people get most of their calories. More importantly, the UAE has a large livestock sector, particularly goats, sheep, and chickens, but cannot produce the fodder to feed them. Producing fresh fruits, vegetables, and dairy is more than just an issue of economic growth, it is a quality of life issue for the UAE’s large population of wealthy people who have been told they will want for nothing in these enormous desert cities.

All of the above makes sense in terms of having a functional economy, but it isn’t reasonable for high population desert nations to not be heavily reliant on food imports, and it is actually insane that Saudi Arabia for decades wasted so much ground water growing something as low value as wheat to export. What is curious about this entire claim though, is that while Saudi Arabia’s large investment in land in southern Egypt is close to the Port in Jeddah and could be fairly easily kept safe in any configuration of world conflict, that isn’t true for the UAE, where to get to Dubai you have to pass out of the Red Sea through Bab-el-Mandeb Strait and then into the Persian Gulf through the Strait of Hormuz, which are the big choke-points everyone always worries will get shut down. There is, in short, no meaningful national security argument for the UAE’s African agricultural investments. It does make a degree of sense to try to insulate themselves from global catastrophe by having their own food supply, except that Abu Dhabi owns 45% of the Louis Dreyfus Corporation, the 4th largest agricultural commodities trader in the world, and that purchase came with a long-term supply agreement. More importantly, they have cash and a huge network of ships and ports and generally work with any country that wants to do business, so them going hungry is unlikely. The reality of the situation is that there is no imperative for the UAE to have its own lebensraum in Africa, it is simply another business opportunity in which to invest their capital and a way to vertically integrate their livestock interests [admittedly, no producer of livestock wishes for his business model to require buying fodder from abroad at market prices.]

The United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia now have massive holdings in both Sudan and Egypt. It can be hard to track exactly what they own as it is a myriad of companies and the farms often don’t have a good reason to have public information on Google Earth, particularly in English, while the Emirati businesses always play a middle ground of trying to impress investors with their business empire while remaining secret enough to avoid what scrutiny they can. Still, you can easily see the contrast between the large center-pivot projects that are generally Gulf investments and the modest fields of the region’s traditional farmers:

This is a matter of particular frustration as these countries have had great population growth but haven’t had the funding to continue expanding their irrigated land and most new irrigation projects, in some instances with high levels of government involvement, are primarily large, foreign purchased operations for the purpose of export. It’s true that it is generally land that was previously unused and the foreign capital purchasing the land also paid for the irrigation to make it viable, but this doesn’t change the fact that all the new farmland which opens up is going to foreigners, commonly at little benefit to the people of the country. Throughout both countries one can see clusters sticking out in the desert:

According to one 2024 estimate, the Emiratis currently control 960,000 hectares of farmland across the world. The farms in Sudan have largely managed to keep running, and exporting, during a brutal civil war in that country that is causing widespread famine and a massive humanitarian crisis. The people of Sudan and Egypt gain nothing from these landgrabs, unless they happen to be of the rare few who have jobs on the farms. Even in situations where the their irrigation isn’t depleting aquifers but is coming from the Nile, that is itself one of the most pressing transnational issues in northeast Africa and the UAE is deeply involved in what are considered Nile River “stakeholder” countries. There is no genuine need to do any of this instead of simply buying grain and fodder, it is just more profitable [in fact, Abu Dhabi’s Al Dahra agricultural subsidiary is also the largest exporter of forage from the United States to the Middle East.] Importantly, unlike the ports, this is exploitation pure and simple and the people of Sudan and Egypt gain nothing from these big GCC agricultural land sales or concessions, while on a national scale it at best puts off paying the price for past irresponsibility.

A 2024 article in Defence24 describes the Emirati acquisitions as follows,

“The UAE has positioned itself, alongside Saudi Arabia and Qatar, as a major buyer of agricultural land in African countries (this practice is called landgrabbing).

Strategic farmland acquisitions are being made by Abu Dhabi in Nigeria, Morocco, Ghana, Namibia or Sudan. In the latter, Emirati investors have purchased more than 400,000 hectares of land, and Al Dahra Agriculture, a company controlled by Muhammad Ibn Zajid’s brother (the current president of the UAE), signed a billion-dollar agreement in 2015 for the use of land in the Al-Jawad Valley.

Last year, the transitional government in Khartoum signed a concession agreement worth US$6 billion with Abu Dhabi Ports to build a new port terminal 200km north of Port Sudan. It will include a special economic zone, an airport and 168,000 hectares of agricultural space.”

This port project is dead due to the Sudanese government’s [credible] claims that the UAE supports their enemies the RSF but this still demonstrates the way their business strategy bypasses the host countries entirely where possible, and in this instance the deal was made with a transitional government that doesn’t have any obvious legitimacy to make a long-term agreement for something this significant that involves sending the country’s wealth abroad almost completely outside of the control of any future Sudanese government.

As well as agriculture, the United Arab Emirates is big into the “sustainability” business, which we should assume is entirely cynical, though it does make sense for a country which does not want to rely on [allegedly] depleting oil reserves.6 Regardless of your views on “renewables”, for an enormous continent with constant infrastructure problems like Africa, it makes plenty of sense to power remote areas with solar panels and batteries instead of from a central power plant. Of the $110 billion the UAE invested in Africa between 2019 and 2023, $72 billion was earmarked for renewable energy. Just one company, AMEA Power, part of yet another Dubai conglomerate, the privately owned Al Nowais investments, is described as having projects in in 19 African countries, as one can see on this map on their website:

I didn’t see a good way to find out how much total land in Africa is currently occupied by UAE renewable energy projects, but it is surely rapidly growing. However, like telecommunications, this is not one of the topics have the intention to get into. What is more significant, and nefarious, is their landgrabs for the ridiculous “carbon credits” scheme: buying vast swathes of land and closing it to economic use so that the “credits” can be sold privately in Dubai. I understand this as a business decision, but why a country like the UAE, that answers to no one, feels compelled to take part in the broader farce is beyond me, but they are also one of the few countries in the world that isn’t led by morons and they seem to have a pretty good idea of the sort of people they are dealing with in European leaders.

Dubai is trying to position itself as a world leader in carbon credit trading. The most important company in this field is Blue Carbon LLC, which is nominally independent but is in fact the business of the Emir’s fourth son by his first wife. Blue Carbon has aggressively sought concessions for land in Africa in order to produce and sell carbon credits. Blue Carbon insists the credits will go to a global market and not simply to be offset the UAE’s “carbon footprint,” which is very high as a major oil producer as well as a small but high population, high quality of life, desert country with little vegetation. Even major organs of liberal internationalism such as Le Monde aren’t buying the sincerity and are reporting on “concerns” that “carbon credits” are just a way for polluters to “greenwash” their environmental impact while the credits themselves do nothing, generally amounting to little more than the keeping existing forests in place. This is of course the entire system, and it’s obvious why the Emiratis would use their capital to profit off of it, but it is less clear why anyone came up with this nonsense in the first place, given that people who believe it has any sort of positive impact are few and far between.

Blue Carbon’s concessions in Africa are enormous. A 2023 CNN article notes they are roughly the size of the United Kingdom, and by extension around three times the size of the UAE. These deals are said to include 10% of Liberia’s total area, 20% of Zimbabwe [an area roughly half the size of France], and big swathes of Zambia, Tanzania, and Kenya. In the case of Liberia, it is said to override a recent law meant to protect the traditional inhabitants of the land, since to qualify for this program the forest concessions drastically limit economic activities, including of indigenous people who live there. The deals are huge though, with the agreement with the chronically bankrupt government in Harare, Zimbabwe having involved $1.5 billion in “pre-financing” from Blue Carbon’s “parent company” Global Carbon Investments [which I can find no evidence exists at all and is probably just a paper/liability sort of thing, but the websites for both are down as of writing.] These forest landgrabs again sell the sovereignty of impoverished African countries and commonly displace the humans who rely on them for income, all for a system that it doesn’t appear anyone genuinely believes in and that would seem to be the most obvious scam even in this absurd modern world. Of course, on top of all of this, it must be mentioned, if the UAE is trying to get into the carbon credit market anyway, where is the profit for these countries in the UAE buying these concessions instead of those countries just selling the carbon credits themselves? Clearly, as is the theme throughout this, Africa’s constantly cash-strapped governments and corrupt, incompetent elites are no match for Emirati money, because the only possible justification for these deals [ignoring that the whole system is a racket] is that the Emiratis can pay less up front instead of the money coming in over time: this is nothing like the other industries featured in this article where it actually requires upfront capital and expertise to develop a port or that sort of thing.

Before moving on, there is one more Emirati land controversy in Africa that cannot be missed. In Tanzania, a firm, lately known as Otterlo, that has been registered under different names and in different jurisdictions for decades offered big game hunting expeditions for the Emirati elite. It is said in that time they were involved in widespread poaching, bribery, and evictions of the celebrated Maasai tribe from traditional villages that involved the Tanzanian government burning their homes. Such disputes have been going on for years, including the Tanzanian government trying to sell 370,000 acres of the Serengeti National Park to the Emiratis for big game hunting in 2014. That same year, a different Emirati company linked to the royal family, known as Green Mile, had a film leak showing prominent men including a top official taking part in terrible and unnecessary cruelties and even so had their hunting licenses re-instated two years later. International courts and pressure seem to have repeatedly made the Tanzanian government back down in these disputes, and around 2022 stories about this conflict stop appearing. However, this is a key example of what I said at the beginning, that the Emirati Royals often seem like the villains in an old cartoon: you can just imagine Jonny Quest helping the Maasai find a legendary diamond so they can buy the park themselves and be protected from the oil-rich Sheikhs who wish to use the land to hunt elephants.7

UAE land acquisitions in Africa show no signs they are slowing down. They also provide the clearest example of how climate change agreements are used by wealthy states to take power over weaker and poorer states. Ignoring their desire to big game hunt, which is no sort of political or economic strategy, the UAE’s entire expansion in Africa is based on the premise of climate change and the end of oil: they need farmland because there will be future scarcity, they are the leader in renewable energy across the continent because there will be a fossil fuel free future, they are buying amounts of land measured as a percent of the country to get carbon credits. I have no idea if the royal families of Abu Dhabi and Dubai believe in global climate change, but there is no doubt in my mind their entire intention is to profit from climate treaties, not to help anyone, least of all, Africans themselves.

Mining: All That Glitters is Gold

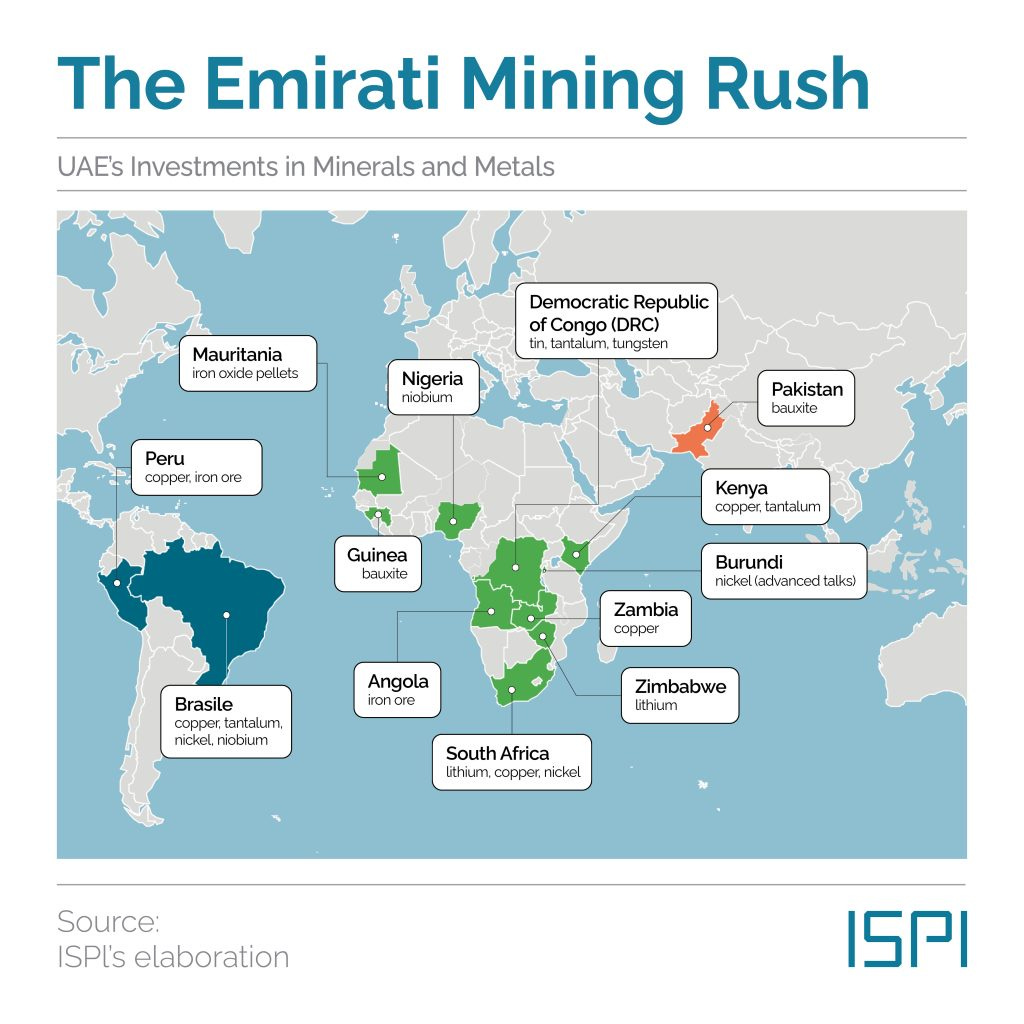

Emirati interests in Africa’s formal mining sector are currently less intensive than in some other areas, and in many instances mining was already a foreign-managed resource, commonly with the states in which it takes place generating much less profit than would wealthier countries. This is an area where other powers have maintained more resources, particularly the Canadians and Russians, countries with enormous mining sectors and expertise. Unlike logistics or desert agriculture, the Emiratis have no specific expertise in mining. Further, many “rare Earth minerals” are primarily available in Africa, or at least only up for grabs there outside of Russia or China. All of these things have kept foreign countries mining in Africa and it is a much less capital-starved and competitive industry than some others in Africa. The formal mining sector is also not somewhere the Emirates can easily “leap frog” technology or avoid the need for existing infrastructure, which has been part of the method of their growth. Still, they have expanded and made some key deals for legal mines as well as prospecting for new sources. What is of greater interest- and concern- is Dubai’s role as the broker of nearly all of Africa’s illicit gold.

Regarding legal mining, the Emirati role is the most interesting in that, as with many other things, it has grown rapidly in recent years. A July, 2024 article from Eleonara Ardemagni at the Italian Institute for International Political Studies [whose work has been crucial throughout this piece] lays out the history of Emirati mining in Africa. The UAE’s first foreign mining investment was a bauxite mine in Guinea in 2013. Bauxite is primarily used to produce aluminum and this investment was seen as supporting the construction sector, though it of course also has defense industry uses. The UAE began expanding its mining interests in Latin America in 2021 [ironically, these investments were made by a firm called JFR Investments, which is owned by an Angolan] and then Emirati interests got more involved in Africa in 2022. That year, the Dubai Investment Fund, an independent asset management company, got involved in a deal to develop niobium in Nigeria, which is used in electronics and aviation. Also in 2022 Emirates Steel, the largest steel company in the UAE, established a joint venture with the government of Mauritania to produce iron oxide pellets.

In 2023, Emirati mining investments ramped up further. Abu Dhabi’s International Resource Holding, a division of the royal families International Holding Company, spent $1.1 billion buying a controlling stake in Zambia’s Mopani copper mine and received a 51% share in the country’s ZCCM Investment Holdings. ZCCM was a state-owned company, making this an egregious instance of an African state simply selling a key asset to a foreign government. In 2024 IRH also signed a deal for two iron ore mines in Angola and worked towards a nickel agreement with Burundi, though it doesn’t seem that has yet gone through. That same year the Primera Group, which is headquartered in the “Royal Building,” though I can’t discover their ownership, signed a 1.9 billion dollar, 25-year deal, with the Democratic Republic of Congo to run four mines of unspecified metals, though generally considered to be tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold. Primera Group is primarily a gold trader and shipped $300 million worth of gold from the DRC in its first year in operation; they also operates 6 gold trading centers in Tanzania, something which they boast of on their website but which I didn’t encounter anywhere else in my research, yet another sign I am only scraping the surface of the UAE’s vast network:

In 2024 yet another Abu Dhabi-based investment company, F9 Capital Management, signed a deal with the South African company Q Global Commodities to produce “green metals” [for renewable energy,] primarily lithium, nickel, and copper, in SA, Botswana, Zambia, Tanzania, and Namibia. The UAE also signed a memorandum with Kenya for collaboration in mining. Earlier this year, since the ISPI article was published, UAE’s Ambrosia Investment Holdings, a newly formed subsidiary of the Al Amry Group, a major UAE conglomerate, made a $500 million deal with Canada’s Allied Gold for 50% ownership share in the Sadiola gold mine in Mali, where they hope to increase production from 230,000 ounces a year to 400,000 ounces a year. Just earlier this month, IRH bought a 56% controlling stake in the Congolese tin producer Alphamin for $367 million; Alphamin claims to produce 7% of global tin at its twin Mpama mines, which also produce tantalum, tungsten, and coltan. Most of the UAE’s African mining investments are just in the last three years, and we should expect them to continue at a rapid pace. It is increasingly the case that the UAE itself mines all of the metals its needs for its burgeoning defense industry.

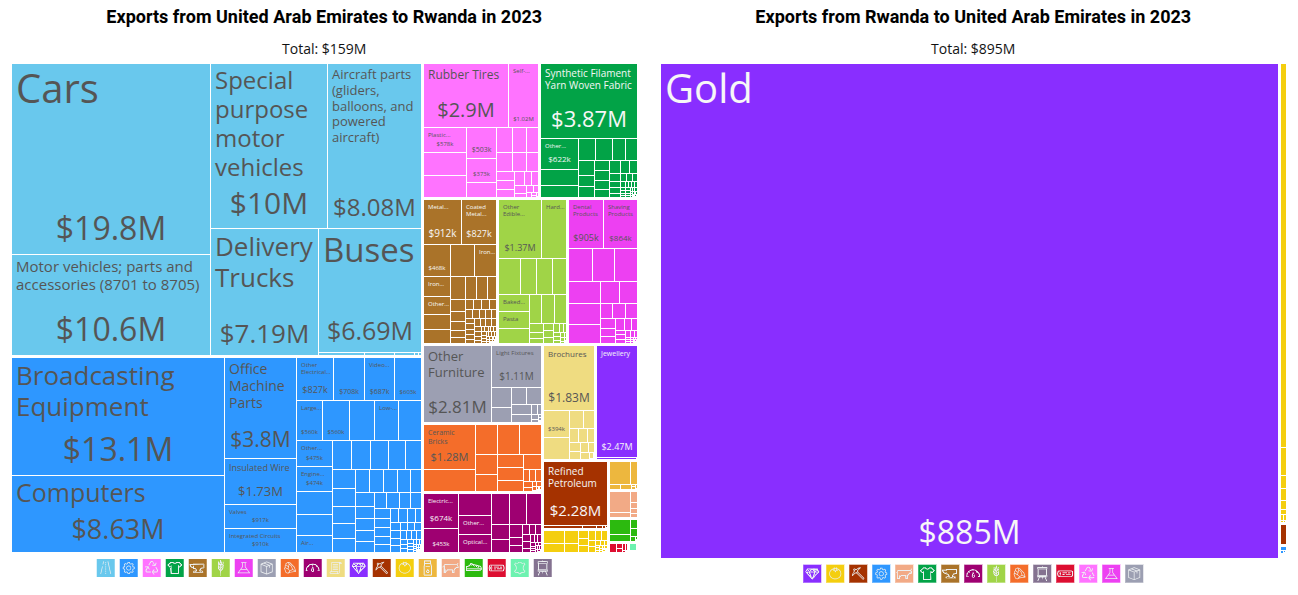

The UAE largest role in African mining is as the broker of Africa’s gold. A great amount of gold is legally exported to Dubai, the center of the UAE gold trade, but much also leaves illegally. This chart of UAE-Rwanda trade provides an astounding view of UAE trade relations with African states:

Regarding illicit gold, the Sahel is in the midst of an unprecedented gold boom since the discovery of a rich vein crossing the region. The boom is driven by the introduction of cheap Chinese metal detectors which allow individuals to find gold across large areas. In other instances there are large unregulated mines worked by countless men in grueling conditions- by some estimates artisanal gold mining employs 1 in 10 people in the central Sahel region. This gets the most notice in Sudan, where it was widely claimed that gold exported from Sudan to Dubai by the Russians is funding the Ukraine War; this claim is nonsense intended to be prejudicial. The reality is that though Russia is involved in this activity, it is a major modern state in the midst of a large, conventional war that is paid for out of its state budget, not the CIA funding the Contras or some militant group. Further, it’s not obvious why Russia should need to broker gold via Dubai instead of just sending it home, it’s not as if they have to launder it to fool themselves. However, countless militant groups, terrorists, and other criminals are profiting greatly off of Sahelian gold, most of it brokered in the UAE, which has largely unregulated gold imports. The most notorious case is Sudan’s Hamdan Dagalo [Hemedti] and his Rapid Support Forces. While the UAE does support his militia, the extent to which this is what allows it to keep fighting is overplayed. The fact of the matter is that gold does not inherently need to be brokered, and he could pay men and buy weapons with gold itself, even if the cost was somewhat more dear than converting it to cash in Dubai. Meanwhile, states struggle to profit from this mining.

Mali, a historic gold producer and once the home of Mansa Musa, provides the best example of this traffic and efforts by states to get their slice of gold production. A 2023 article says that Mali only records 4-6 tons of artisanal gold produced annually, but that officials estimate the total is 30-50 tons, while an investigative journalist for France24 estimated the number is over 60 tons. It is said that gold miners from across the region travel to Mali’s capital of Bamako to sell their gold and further that transnational criminals come to the country to launder money, which is as easy as buying gold and then taking it to Dubai to trade for cash. Bribes to take the gold out of the country are inexpensive. It is noteworthy that there are not currently direct flights from Mali to the UAE, however a Dakar-Bamako corridor is a key goal of the DP World port project at Ndayane. It is usually left unsaid, but with the UAE controlling African ports, such as in Dakar and Algeria, any smuggling that is Emirati-approved is basically impossible to track because they control the shipping apparatus from start to finish. Nigeria has attempted to get the UAE to take a more “responsible” role regarding gold imports, and the Emiratis agreed to cooperate on regulating Nigerian gold imports, but it is not obvious it has accomplished anything, and Nigeria is one of the few states in Africa with a large enough economy that the Emiratis have to make a show of treating them as an equal.

Part of the reason Mali became a center of gold exporting is that until recent policy changes aimed at increasing sovereignty and state revenue, there was a cap on export taxes after 50 kg. One estimate has 80% of Senegal’s artisanal gold entering Mali to be sold. The scale at which African gold is moved to the UAE is eye-popping: estimates are that 405 tonnes of artisanal gold- around 90% of the continent’s artisanal production- ended up in the UAE in 2022. It is believed that between 2012 and 2022, $115 billion worth of illicit African gold entered the UAE, and that period begins early in the current gold boom that has seen large production increases. A recent report found an $11.4 billion annual gap in Ghana’s gold exports and the amount reported as having been imported from Ghana, with most of it going to Dubai via Togo.

Dubai is awash in African gold. You need to see its Gold Souk for yourself before I continue:

Dubai’s Gold Souk is home to over 380 retailers selling the gold that is primarily extracted from Africa.

The reason Dubai has become a gold hub is in large part that they don’t follow the standard practices for high-value objects when it comes to gold. Anyone can enter Dubai carrying physical gold and they are not charged any taxes or made to prove they acquired the gold legally or ethically or that they paid export taxes. You are simply given a card saying you declared the gold at customs, and you’re home free. It is said that the Gold Souk is heavily regulated, but it is regulated in the sense that God knows what they would do to you if they catch you selling fake gold, not that there are any tracking mechanisms in place.

Gold is the UAE’s top import and its #3 export, after crude oil and refined petroleum. In 2023 imported $75.2 billion in gold and exported $46.8 billion, a nearly $30 billion gap, reflecting a rapidly growing horde of gold stored in Dubai’s vaults or at the homes of its citizens; the UAE’s 2023 GDP was around $500 billion, meaning the country is presumably adding over 5% of its GDP to its gold vaults on an annual basis. It would seem to be the case that when tourists buy jewelry and leave it is recorded as an export, as one travel writer stated that you can get a VAT refund at the airport, so this isn’t explained by a lot of people buying jewelry and then leaving with it. Much of the capital by which the Emiratis are buying state functions in Africa is clearly based on African gold, from which the African states themselves often fail to profit. It is said that Emirati goldbuyers love cheap African gold bars as they may contain the more valuable metals of palladium and platinum when they are melted down again in Dubai’s more sophisticated refineries. Mali’s military government, with Russian support, has just broken ground on a new gold refinery and is hoping to end the export of raw gold from the country, but it seems that it will be near impossible for any state to stop this traffic.

The UAE’s wealth and lax gold policies are fueling conflicts across Africa, particularly the Sahel, and that is true even of what conflicts they don’t intentionally involve themselves in.

War: A Dog in Every Fight

The United Arab Emirates was a small and weak state until about 20 years ago, and its role in global affairs primarily arose from its willingness to act as a transit point for its Anglo-American allies. This began to change in 2011 when the UAE was a direct participant in the NATO-led operation to overthrow Libya’s Gaddafi. Then, the Emiratis became involved in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia’s brutal and anti-human war on Yemen’s Ansar Allah [“Houthis”], notably employing Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces as mercenaries, while the KSA was employing the Sudanese Armed Forces in the same capacity [this being years before the two factions turned on each other.]

In the last 10 years the UAE has built a network of partners across the region, some of them states and some of them secessionists or other non-state actors. In his book The Abiy Project, about Ethiopia’s controversial Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed, Tom Gardner quotes from EU special envoy to the Horn as saying, “The Emiratis don’t invest in states, They invest in individuals” [138.] And invest in individuals they have: the aforementioned Abiy in Ethiopia, whom they supported in the brutal Tigrayan War, as well as Hemedti in Sudan, Haftar in Libya, Deby in Chad, and more. Analyst Andreas Krieg described them as building an “Axis of Secessionists” across the region, that he compares to Iran’s “Axis of Resistance.” The Emiratis favor a model of light and temporary military outposts they are willing to fold if they lose value and modular drone technology they ship unassembled under the guise of civilian supplies. All of this is backed by their love of the gold that tends to fund such groups- and willingness to let it go untracked once it enters Dubai- and a burgeoning UAE arms industry where they both broker the weapons of others and manufacture their own. It isn’t just Blackwater’s Erik Prince, famously now a Dubai resident, but any entrepreneur of violence, so long as he is “counter-revolutionary,” that finds the world’s best ally in the Emiratis. Arms manufacturers move to the UAE because it has extremely lax export controls on weapons and you can sell arms to people whom you might face prosecution for doing business with in the US, Canada, or Europe.

Of everything about the growth of power of the UAE, I find their role in these conflicts the most concerning because I don’t understand the purpose of the web they are weaving, but there seems to be more too it than simple profit. I don’t find any of the popular explanations compelling. Krieg describes what the Emiratis have achieved with this as follows:

“Through this axis, the traditional, small state of the UAE has been elevated to a regional great power, achieving far more effective levels of entanglement and interdependence than its larger neighbour Saudi Arabia, or its agile neighbour Qatar. For Abu Dhabi, this network has become the bedrock of strategic autonomy to pursue its own interests - even when at odds with western interests and values.”

On top of being somewhat generic, the problem with this line of reasoning is that the Emiratis have an enormous horde of gold and oil and are deeply involved in global shipping, so that itself gives them strategic autonomy. Further, they clearly have the ability to buy off national governments instead of, as is the case in Sudan, antagonizing them to the point that they get sued for genocide over their support of a non-state actor as well as losing the deal to develop a port which would have proven quite lucrative. True, they could have just picked the wrong side, but this falls into a pattern.

Eleanora Adremagni at ISPI describes Emirati foreign policy actions in Africa as following three patterns,

“1. The first is the countering of jihadi terrorism (al-Qaeda; IS), insurgent groups related to the Muslim Brotherhood (an organization the UAE lists as terrorist), and piracy… 2. The second pattern regards military provision and cooperation in the defense industry sector: the goal is tightening stability-oriented partnerships with governments in countries where the UAE invests. 3. The third pattern relates to the Emirati reported activity in conflict landscapes (Libya; Sudan; Ethiopia), usually denied by the Emirati authorities, to enhance its influence through the military support to non-state armed actors.”

Put together points do not make a coherent strategy nor is much of it justified as anything besides playing power games for its own sake. Their fighting piracy makes perfect sense as people in the business of shipping around the Horn- though it is a grand irony that the very premise by which they were once made an imperial protectorate is part of their basis for expansion. Regardless, this only explains supporting Puntland and Somaliland even if it upsets the Mogadishu government, though they also back the Mogadishu government in its war with Al Shabaab [the fiction that DP World, owned by the Prime Minister, is meaningfully different from the UAE government is doing some heavy lifting here.] However, why the UAE should be obsessed with the “Muslim Brotherhood” has never been clear to me, and they do indeed use it as a catch-all in the same way as American right wingers who hate Islam do, not necessarily meaning any particular organization in this context.

It is said that the UAE were spooked by the “Arab Spring” and this led to their pursuing hostile policies towards terrorists in the region. Ignoring the seeming futility of wars on terrorism in general, the idea that radical Islam poses a threat to the UAE does not withstand scrutiny. The UAE does not face any meaningful threat of terrorism or being overthrown by its people because it follows a Venetian citizenship model and a “social contract” that prioritizes the citizens, so there is no submerged and marginalized class of Emiratis from which terrorists would generally arise. On the other hand, there are millions of South Asians in low-skill jobs, which could present some threat, but they have high state capacity to monitor such people. Perhaps more importantly, while it’s true that radical Islamic terrorists are by definition ideological maniacs, the successful ones such as Al Qaeda and IS tend to have a level of pragmatism where they avoid starting problems with the sort of place where they can turn illegally mined gold into legal liquid assets.

If you’ve made it this far, please consider a paid subscription. As you can imagine, it takes a lot of work to write something like this, which is time I can’t spend writing for outlets that pay. Thank you!

As to number two, it is certainly true that they want cooperation in the “defense industry sector” because the UAE is trying to increase its share of the arms business and, in general, one country, especially a small and domestically peaceful one, does not need enough military equipment to keep the factories running. The idea that the Emiratis want peace and stability in the countries in which they invest also doesn’t stand up to scrutiny as they are quite obviously profiting from instability and a lack of state capacity. If the UAE wanted to help African states stabilize and build capacity it would follow global standards requiring gold importers to prove they paid export taxes in the source countries and to demonstrate the gold was mined legally in a way that doesn’t fuel militant groups: it is state policy to do neither of those things.

As to the third one, yes, arming various actors in civil conflicts is what they are doing but the question is to what end?

The UAE has made foreign policy moves all over the continent with various training agreements, weapons sales, and more. Here is a rundown of Emirati military activities in Africa, again following Ardemagni:

From 2014-2018 supported Somalia’s government, including paying their soldiers. A new agreement in 2023 saw the UAE returning for more training and funding, and deploying military vehicles to the southern state of Jubaland, which would later get into its own armed conflict with the central government.

Supporting Puntland Maritime Police Force since 2012, including paying the salaries of its 2000 personnel.

A 2018 agreement with Somaliland for a training program for local police and military, as well as building a military airport in Berbera.

Training the Republican Guard in Ethiopia, a force created in 2018 that reports directly to the Prime Minister.

2023 military cooperation agreement with Chad and helping to guard their border following the coup in Niger. In 2024 the UAE deployed troops in a training capacity. It is widely believed the UAE is using Chad to smuggle weapons to the RSF in western Sudan.

In 2016 the UAE established the Mohammed Bin Zayed Defense College in Mauritania, with the intention of training officers from the “G5” countries, a French-backed counter-terrorism alliance. this is now shut down as the alliance is defunct, following a series of anti-French coups that ultimately saw three member states form their own alliance [AES.]

In 2019 the UAE and Mali signed a training agreement that also involved the UAE supplying a large number of armored vehicles made by the STREIT Group, a vehicle manufacturer based in the Emirate of Ras Al Khaimah [RAK.] Some or all of the vehicles were donated but available reports are unclear.8