Will Donald Trump Make Somaliland Great Again?

The Case for Recognizing Reality on the Horn of Africa

“All must have been but only one universal monarchy if men had not been at liberty to separate themselves from their families, and the government, be it what it will, that was set up in it, and go and make distinct commonwealths and other governments, as they thought fit.”

- John Locke [The Second Treatise of Government, 115.]

Note: In situations such as this the use of names can become a matter of great political significance. Throughout this article at various times I use “Somalia” to mean the historic region, the Federal Government of Somalia in Mogadishu, and the internationally recognized territory. My meaning should always be clear from context. This carries no political intention and I [obviously] understand that the Republic of Somaliland government does not consider Somaliland to be part of Somalia. Further, though the proper denonym is generally “Somali,” for the purpose of clarity I will be using “Somalian” to mean “citizen of the Federal Republic of Somalia” and “Somali” to mean the ethnic group. I will most likely be ignoring any comments lecturing me about my use of proper nouns.

The inauguration of Donald Trump was a cause for widespread celebration in an unexpected place: Somaliland, an unrecognized republic on the north coast of the Horn of Africa. Now fully self-governing for 33 years, Somalilanders feel that their intensive and targeted lobbying of American Republicans is about to pay off. Republicans, including Donald Trump, are tired of pursuing dead-end policies which provide little to America, and there are few better examples of this than our 30 year commitment to Somalia. Alternately, though of humble means, Somaliland has managed to maintain a remarkably stable electoral democracy in relative peace as the rest of Somalia has been racked by war, piracy, and terrorism. What’s more, the Somalilanders are desperate to be useful allies of America in return for what they want the most: recognition. The top two Africa specialists in Trump’s orbit are outright Somaliland partisans, while the Republican head of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, Idaho Senator Jim Risch, has expressed persistent skepticism of the “One Somalia” policy which has been pursued by past administrations. The long-standing Somalia policy has borne only bitter fruit, while Somaliland is capable of providing more to the United States for a lot less effort. It is plausible, though far from certain, that this combination of circumstances will lead the Trump Administration to take the plunge and make the United States the first country in the world to recognize Somaliland as Africa's 55th state.

The legal and strategic arguments for recognizing Somaliland are strong. However, I would make an even simpler argument for the United States recognizing the independence of Somaliland: because it is true. Not just in the strategic “realism” sense, but in the general “reality” sense, Somaliland is an independent state. While they lack perfect control of the old British borders, the government in Hargeisa physically controls a mostly fixed area, collects taxes, pays its own military and civilian employees, conducts international relations, and even chooses its leaders though competitive elections. In short, Somaliland is a state. The benefits the US could gain from recognizing Somaliland, which has said it would allow a US naval base, are clear. The pride Somalilanders would take in attaining international recognition is also clear. The question that is rarely asked, however, is “would international recognition make Somaliland any better?” It isn’t obvious that it would, and if anything it may be the case that its relative isolation from international aid, “NGOs,” and the entire mess of nonsense that comes with the Western “liberal internationalist” power structures are the primary reason that Somaliland has one of the few generally functional and fairly elected governments in sub-Saharan Africa.

Though Somalia is an ancient land and Somalis are an ancient people, the history of modern Somalia begins in 1960 when, just days after independence, former British Somaliland joined the Trust Territory of Somaliland [formerly Italian Somaliland] to form the Somali Republic. At the time, Somalia was considered to be at an advantage over the rest of sub-Saharan Africa as the only homogeneous state of any size, with the overwhelming majority of the population tied together by custom, language, religion, and a complex clan system where five large clan-families formed the Somali nation. A proud race of nomadic camel-herding warrior poets known for carrying on feuds of Byzantine complexity, the Somalis have impressed adventurers as much as they have exasperated administrators.

Unlike the other newly independent countries in Africa where it was a challenge to create a unified national identity transcending ethnicity, the Somalis were already fiercely nationalistic. The aspiration of the Somali Republic was to be the government of all of the Somali people. As their flag they adopted an ethnic flag of the Somali people, a five pointed star, representing Italian Somaliland, British Somaliland, French Somaliland [Djibouti,] Ethiopia’s Somali Region [the Ogaden,] and Kenya’s North Eastern Province. The new state was in several ways designed to bring in the Somalis outside of its borders and also advocated for their autonomy under the governments which ruled them. This created a great deal of well-founded suspicions in Somalia’s neighbors, who feared both a Somalian invasion as well as revolts from the famously restive and ungovernable Somali people, whom the journalist David Lamb described in the early 1980’s as having, “never willingly yielded an inch or lost an ounce of spirit” [The Africans, 197.] The new Somalia made it clear it had little respect for current borders, some of which were quite poorly defined, running as they do through camel grazing land with few distinct features.

The marriage of the Italian and British Somalilands was the closest the Somali people have come to political unification, but there was quickly trouble in paradise: Somaliland, the name British Somaliland retained as a province of the new Somali Republic, rejected the 1961 constitution and thus almost immediately found itself in a political union it no longer agreed to. Still, the Somali Republic maintained a fair amount of political freedom with an involved and represented population and it was indisputably the high-point of post-independence Somalia. In 1969 this government was overthrown in a military coup by the socialist dictator Siad Barre. Somalia’s complicated clan system, where children are expected to know their male lineage going back 10 to 20 generations, had always made politics terribly unstable, but even under Barre things did not get really bad until he launched the Ogaden War, seeking to annex Ethiopia’s Somali Territory into the Somalian state. The Soviets, who had sponsored his regime, switched sides and aided the Ethiopians, leading to a crushing defeat of Somali forces. As Martin Meredith describes it in The Fate of Africa, “For as long as the goal of a “Greater Somalia” seemed attainable, clan rivalries were held in check. but when the government’s irredentist campaign ended in a humiliating military defeat, it set in motion an implosion of the Somali state” [466.] As it would turn out, far from ethnic uniformity being a strength, the Somali clan system was a more fertile ground for conflict and mass slaughter than was found in any multi-ethnic state in Africa, excepting Rwanda/Burundi.

Following the defeat in Ethiopia, the Barre regime faced multiple revolts, some backed by Ethiopia. The most notable of these, especially for our purposes here, was the Somali National Movement, primarily made up of the Isaaq Clan of Somaliland, which began an armed rebellion in the early 1980’s. The Barre regime failed to suppress the rebellion for several years and between 1987 and 1989 turned to extermination tactics. What is now known as the Isaaq Genocide killed perhaps as many as 250,000 people, though 50,000-100,000 is the more common estimate. Several hundred thousand more were displaced, while the two largest cities in Somaliland, Hargeisa and Burao, were mostly destroyed. It should be noted that while the horror of this extermination campaign is not in question, in my experience, Somalilanders have a tendency of blaming this on Somalia as a whole, which is not really fair given that much of the country was also in revolt against the Barre regime at the time that his military perpetrated these crimes. Regardless, the SNM, which had previously been seeking to overthrow Barre, turned its sights to independence in response to the atrocities committed against their people.

Having switched sides in the Cold War after the Soviets betrayed him in favor of the Ethiopians, the Barre regime had become an enormous recipient of American military aid upon which it became completely reliant. This dried up in the wake of the Isaaq Genocide, and the man who by then was derisively known as the “Mayor of Mogadishu” was overthrown at the beginning of 1991. Somalia collapsed into brutal anarchy, becoming the archetypal failed state. The journalist Aidan Hartley, who was in Somalia at the time, described the situation as follows,

“All lines to Somalia went dead and for years afterward if you dialed the national code 252 all you heard was electronic ether, ghostly distorted voices and lonely Morse signals repeated like pleas. An entire nation of people was lost, beyond reach, tumbled into the abyss.” [The Zanzibar Chest, 193]

An entire nation, that is, besides Somaliland. On May 18th, 1991, the SNM lead a group of clan sultans in signing a Declaration of Independence reverting Somaliland back to the independent status is held for 5 days in 1960. The SNM leadership quickly made peace with rival clans in the territory, began the work of building a state, and after two years of transitional government held democratic elections. Somaliland is deeply impoverished- the GDP per capita is a mere $871 in 2023- and it has faced a variety of challenges, including at times violent conflict, but compared to Somalia and even other regional states the level of freedom and stability is nothing short of a miracle.

The Somalian government in Mogadishu, on the other hand, has never come close to controlling all of its territory since the fall of Barre and many of the parts it does primarily control have remained quite dangerous. It is beyond my scope or ability here to explain the vicissitudes of Somalian fortune, but Americans will be familiar with our interminable involvement in the country, which after over 30 years still has a security situation where our diplomats rarely leave the international airport. The country has seen a succession of foreign invasions, occupations, and peacekeeping missions. A terrorist insurgency continues to rage through the countryside. Somalia is primarily known for Hiluxes with heavy weapons, piracy, terrorism, and refugees. It is also known for corruption, rating dead last in the world in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index [it should be mentioned that I hate such NGOs, but don’t know of a better source of this information.]

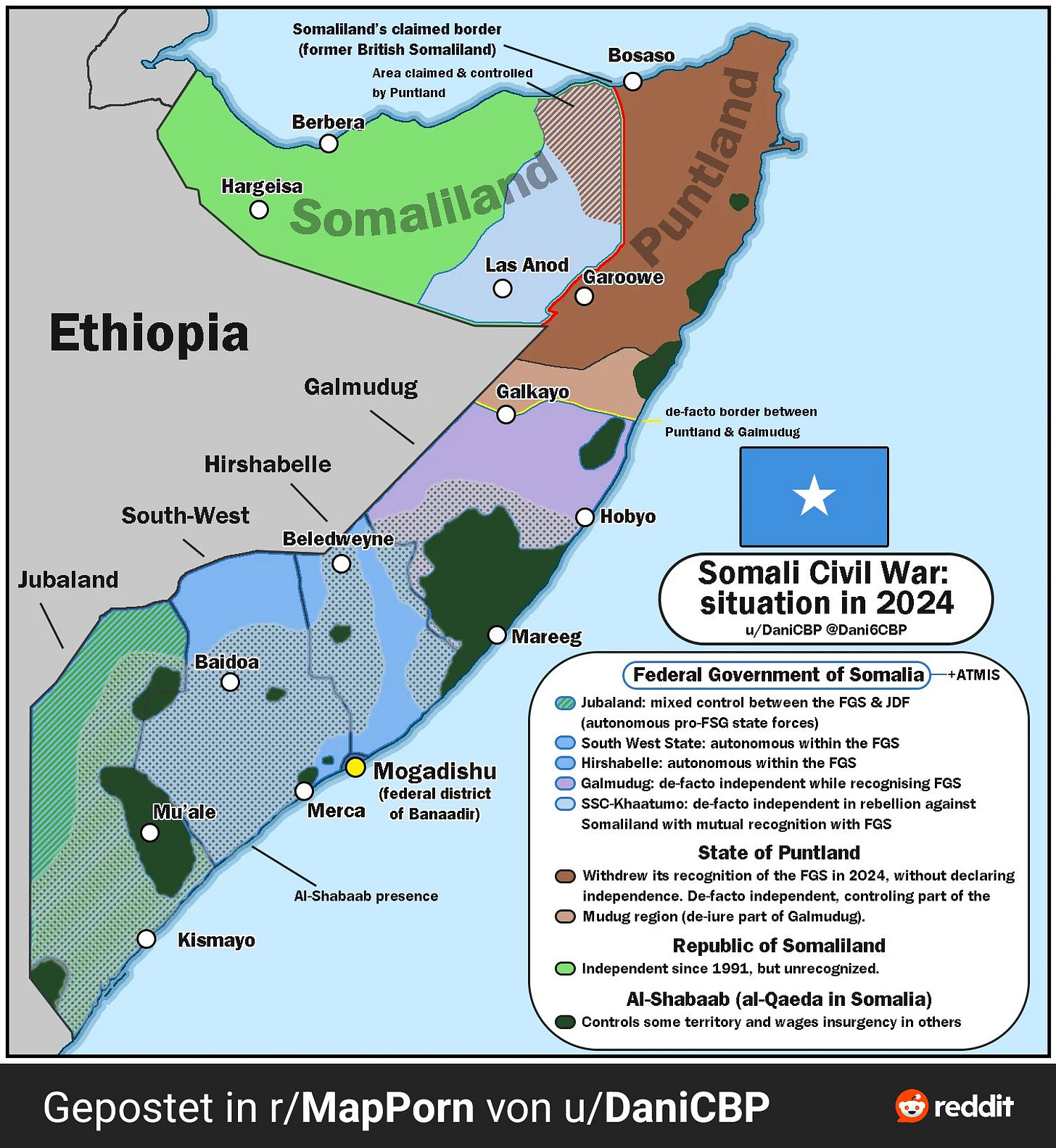

Mogadishu itself is quite a bit better both in terms of economy and security than a person might expect, but that isn’t saying much, given that the name of the city once known as “The White Pearl of the Indian Ocean” has become synonymous with extreme violence and deprivation. Puntland, the northeast corner of Somalia, which unilaterally declared autonomy many years ago, is more peaceful than the rest of the country, but that is kind of the point: centralization hasn’t worked. Just last year, after more than 30 years of expansive international state-building assistance, Puntland withdrew recognition from the Federal Government in a dispute about the federal constitution, while Jubaland to the south won a series of battles against the Somali National Army following a dispute about Jubaland’s constitution.

Throughout the almost 35 years of post-Barre conflict in Somalia, the United States has primarily maintained a “One Somalia” policy, which somewhat ironically operates almost exactly the opposite of the “One China” policy. Whereas the “One China” policy, a curious piece of diplomatic fiction, only recognizes the People’s Republic of China as the government of China and Taiwan but the US maintains close unofficial relations with Taiwan and more or less treats it as a protectorate, the One Somalia policy is to only work with Mogadishu. It has also been the policy to support a strong central government in Mogadishu, which by now has been clearly shown to not be a viable solution to any of Somalia’s problems. Besides trying to stop terrorism and piracy from festering- which hasn’t been so successful, by the way- Somalia is of little strategic importance in the modern world. In fact, while you could just sail wide of Somalia, it is Somaliland with its coast towards Yemen and the entrance to the Red Sea which holds the greatest strategic significance of the Horn. The most strategic part of Somalia that hasn’t seceded, Puntland, no longer recognizes the Federal Government, and the US should probably also seek to engage them directly. Supporting the Mogadishu government is a zombie policy which only moves forward under its own weakening inertia. The one thing Somalia has going for it is that after almost 35 years of chaos there are quite a lot of Somalians in Western countries to lobby in favor of pouring tax money into the world’s most corrupt country.

It needs to be emphasized that while war in Somalia has gone on that entire time, Somalia and Somaliland were only the same country at relative peace for 20 years, ending over 40 years ago. Further, like most of Africa, Somaliland is a very young country, with their Bureau of Statistics giving a fertility rate of 5.9 children per woman, though it isn’t further broken down. Internationally recognized Somalia as a whole, including Somaliland, is said to have a similar birth rate of 6 children per women so we can assume Somaliland has roughly identical age demographics. Around 42% of the population of Somalia is 14 or younger. If we extrapolate from that number, we have to assume that well over 2/3rds of Somalilanders were born after the Declaration of Independence, and that under 10% are old enough to have any memory of a time before 1980 when Somaliland was part of Somalia and there was internal peace [only 2.27% of Somalians are over 65, compared to 17.7% of Americans.] At least two generations have grown up with these countries entirely separate, as Somalia has failed to stabilize and Somaliland has sought recognition of its independence.

The more than 30 year quest for recognition has created an interesting breed of Somaliland activists. They have a tendency to be well-educated expatriates, commonly in the United Kingdom, who are proud and patriotic. They are deeply interested in geopolitics and recognize the value of their geographical location to Anglo-American interests and are eager to show how they can be of use to us. They tend to be anti-Islamist and supportive of Israel. Most strongly oppose China’s presence on the Horn- Somaliland having ties to Taiwan instead of the PRC. They are strangely proud of Somaliland’s history as a British colony compared to Somalia having been Italian, which makes them unique in Africa at a time where discussions of colonialism almost always center around historic grievances against the colonizer. Somaliland activists are also hateful of Somalia beyond reason, often portraying Somalians as genetically inferior savages, calling the country “Zoomalia,” and never saying the name “Somalia” without making sure it is immediately adjacent to “failed state.” It is understandable that they are frustrated that Somalia can’t get its own house in order but also won’t let them go, but in many ways it seems more appropriate to pity their brethren, and the entire NATO order they want to serve bears responsibility for propping up the Mogadishu government, so it could just as easily be said that we are their enemies. They also sometimes claim Somaliland was never part of Somalia at all because the 1961 Constitutional dispute invalidated the union. I dislike legalistic arguments of this nature when the reality of Somaliland’s current independence is there for all to see, but this one is reasonably compelling, with a 2005 African Union fact-finding mission agreeing that the union wasn’t ratified properly.

Somalians who oppose Somaliland independence certainly also criticize Somaliland, but while it is distinctly less hate-based, they are completely unable to explain how Somalia could possibly reincorporate Somaliland- against its will, mind you- into a state which is an international ward and hardly controls the other parts of its territory. The two governments are almost like the ant and the grasshopper, and it is understandable that Somaliland which has spent over 30 years successfully building a state with little help has a low opinion of Somalia, which is a black hole of international financial and security assistance and still hasn’t got very far. I am also reminded of the situation between the Ukrainians and Russians, where Ukrainians harbor deep-seated ethnic hatred of Russians and Russian culture, well predating the war, whereas Russians seem to regret that the situation came to conflict.

Regarding both sides advocating for themselves, Africans tend to be quite a bit more savvy at playing the white man than is commonly realized, and know that we have a tendency to take the side of the first group we happen to speak to. Americans and Western Europeans specifically are trained from early childhood to consider all of the prejudices within our own society as both inaccurate and wrong, but then fail to apply that to what they hear from anyone outside of our culture. Americans in Africa can be as Rebecca West said of Englishman who go to the Balkans,

“Unable to accept the horrid hypothesis that everybody was ill-treating everybody else, all came back with a pet Balkan people established in their hearts as suffering and innocent, eternally the massacree and never the massacrer.” [Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, 20]

It is unclear to me how Africans learned this about us, but they know it. It doesn’t work on me, but not for a lack of trying. Somalilanders have found a good target in American Republicans, who have rightfully grown hostile to our futile nation-building projects, especially in Africa. Further, they dislike the refugees from what Trump calls “shithole countries” filling up our cities. Last year, the Somalilanders had a masterstroke when one of their Ambassadors released a false translation of the Somali-American Congresswoman Ilhan Omar speaking to a Somalian political group. This played into several reasonable concerns of Republicans, who were quite effectively psyopped by the whole thing. I actually hate that our country is full of endless ethnic lobbies and that there is no place too obscure to not have someone in its pocket in Congress, but what Omar was saying reflected long-standing US policy from before she entered Congress, or even the country. Regardless, with a sustained lobbying campaign and a few notable good moves, Somaliland has done an impressive job of making inroads with Republicans.

As far as Trump’s possible policies towards Somaliland, it should be noted that the “Project 2025” we kept hearing about, put out by the Heritage Foundation, happened to call for recognizing Somaliland as a “hedge against the US’s deteriorating position in Djibouti,” which also let China build a base in the country. While Trump himself denied knowledge of the long and probably very boring document, it is an indication of the views of key people in the Republican think tank sphere. There is also Congressional support for Somaliland. At the end of the last Congressional session, Pennsylvania Representative Scott Pretty introduced a bill to recognize Somaliland as an independent country. He is just one representative, but more important is that Idaho Senator Jim Risch, the head of the Foreign Relations Committee, is an opponent of the One Somalia policy. Though he has maintained appropriate professionalism and hasn’t called for recognition of Somaliland, he is a proponent of working with the Somaliland government. In 2022 he introduced legislation called the “Somaliland Partnership Act.”

More importantly than some policy paper, and perhaps even the legislature, is that the two top Republican Africa hands are total Somaliland partisans, to the point that it is quite unprofessional, especially considering our country’s close relationship with the Mogadishu government. The first is Tibor Nagy, a career foreign service officer who has been appointed the Undersecretary of State for Management. Nagy has over 20 years of experience in Africa, and as a great piece of trivium, his three sons were the first triplets born in independent Zimbabwe. Here are a couple of his Tweets on the matter:

He isn’t wrong, especially about accepting reality, but you can look through his Tweets mentioning Somaliland and I would just say I would expect a career diplomat to be a bit more…diplomatic.

Secondly, though it is not official, it is expected that Africa scholar J. Peter Pham will take the top State Department position overseeing Africa policy. Somalilanders are jubilant about this choice, as in that position he is sure to push for closer relations between or countries. Pham, a Distinguished Fellow at the Atlantic Council, had this to say about our Somalia policy in a November opinion piece about Africa policy in Trump’s second term,

“In his first term, President Trump correctly assessed that there was neither a capable local partner in the Mogadishu regime nor any US national interests that warranted risking American lives or treasure on the ground in Somalia. He ordered US military personnel pulled out. Any threats posed by al-Shabaab, the Qaeda-aligned Islamist movement, or the Islamic State’s local affiliate could be dealt with from offshore or bases in nearby countries. The Biden administration reversed this Trump order, which will need to be revisited after the inauguration.”

Here are some of his recent tweets on the subject:

Again, he is not wrong, but this is a really unprofessional way to behave, and I would add that I dislike him generally for being an Atlanticist and having a global chessboard attitude towards Africa that we need to move past. You can see why Somalia would be panicking, and indeed they’ve already brought on a lobbying firm to deal with a Trump Administration they expect will be difficult for them [I can’t shake the feeling that they are using our own money to lobby us to keep giving them money. What a racket.]

I need to make a quick digression and note that while I am not much of a fan of either of these men, it is interesting that the top Republican Africa operatives are a Hungarian guy and a Vietnamese guy who are genuine Africa specialists. The flipside of what I was saying about Africans being savvy about dealing with whitey is that Americans have a tendency of wanting to send a black person to Africa for the “optics,” something which Africans have always found condescending, preferring to work with a qualified person of substantial authority. Perhaps the all-time most absurd example of this was Biden sending the Housing and Urban Development Secretary to Nigerian President Bola Tinubu’s inauguration, which was insane because Nigeria is the most important country in Africa and HUD is already a cabinet position famously reserved for black people which has absolutely nothing to do with international relations. This was made even worse by the fact that Nigerian election was marred by widespread reports of fraud and Nigerians were looking to the US for a strong position on Tinubu’s legitimacy. While a bit to the side of the point, this story provides a clear example of just how badly Africa policy was ran under Biden.

Faced with an administration employing people who actually know about Africa and are hostile to Somalia, Somalia’s Ambassador Dahar Hassan Abdi wrote a bizarre op-ed in RealClearWorld which seems to serve little purpose but to deny reality. Writing at the Hudson Institute [which it must be noted is completely funded by Western financial interests] another one of Somaliland’s supporters in the Republican orbit, Joshua Meservey, wrote a terse and amusing response titled, “Seven Inaccuracies about US Support for Somaliland.” I suggest you read the whole thing, but this is my favorite line,

“4. “The United States must remain committed to Somalia’s sovereignty within its recognized 1960 borders—an enduring policy that has helped stabilize one of the world’s most strategically vital regions.” This is one of Abdi’s strangest claims. Somalia has consistently been among the least stable countries in the world since 1969, and it has in turn caused massive regional unrest. US policy built on the fiction that Somalia is a unified nation with territorial integrity has demonstrably failed.”

In short, there is no stability or unity to be preserved in Somalia, and it is absurd to pretend otherwise. If anything, recognizing this and promoting a more decentralized Somalia is likely to bring at least relatively better stability. I don’t think it is speculating too irresponsibly to imagine that opportunities for corruption are a primary reason Somalia’s ruling class wants to make sure as much as possible runs through Mogadishu.

What are some more reasonable objections to recognizing Somaliland than the claim that it would somehow disunify Somalia to recognize an area they haven’t controlled in over 30 years? For starters, it would upset the African Union, which is full of states with various secessionist challenges and which is, in general, extremely hostile to states breaking up. South Sudan was an exception because Omar Bashir agreed to it, more or less thinking he wouldn’t have to let it happen [that is a story for another time.] Regardless, South Sudan had the permission of the internationally recognized central government, which Somaliland does not, even if it has not been under Mogadishu’s rule in decades. International law is largely pointless here, as it is designed to be subjective and at the interpretation of the world powers, but this also means the US has a fair amount of leeway to make an argument why it should be allowed; everything else going on in Somalia would seem to imply it would be bad for the safety of Somaliland to come back under the rule of Mogadishu. It needs to be added that Somalia has no meaningful leverage over the United States, so their being upset is not a big downside and in fact falling out with the Federal Government of Somalia would be more likely to save us money than to cause us grief.

One criticism of Somaliland that seems reasonable is that it is largely a project of one clan. I fail to see how this is a bad thing, given what has happened to Somalia trying to cope with clan alliances and feuds. While Somalia has a complex “4.5 system” to try and balance power between tribes, Somaliland, with an Isaaq supermajority, has managed to have one-person one-vote elections and it seems to me its better, politically at least, to be a minority in Somaliland than to be anyone in Somalia [though parts of Somalia, including Mogadishu, are substantially less impoverished than Somaliland.1] Perhaps most importantly, though the Isaaq are socially dominant in Somaliland due to their numbers, the minorities have political rights. In fact, the third President of Somaliland, Dahir Rayile Kahin, is of the Dir clan, and though he was initially a Vice President who inherited the office when the President died, he won the next election, indicating that a lot of Somalilanders are willing to vote for a candidate outside of their clan.

Still, democracy in Somaliland has had its challenges, such as the most recent election being delayed for quite a long time, but it was ultimately conducted fairly and the results were respected. Alternately, in that bastion of liberal democracy, the European Union, Romania just straight cancelled an election on spurious grounds because they didn’t like the results and all the NATO countries thought that was great- an inspiration even. It should be further added that though the election was delayed two years, President Bihi conceded defeat. Peaceful transfers of power at all are uncommon in Africa, but a sitting President conceding defeat in an election is almost unheard of, though Liberia’s President George Weah impressed the whole continent when he conceded a close election in 2023. The great majority of African Presidents serve until their term limit [or perpetually change the constitution to extend term limits,] die in office, or are violently overthrown. Neighboring Djibouti, which more or less relies on leasing its ports to outside powers for legitimacy, has had the same President since 1999. Some critics contend that Somaliland’s elections are just an exercise in elite power sharing that do little to improve the conditions of the people, which, if true, should not only qualify Somaliland to be an internationally recognized state, but should fast-track it for European Union membership. On a more serious note, there have also been allegations that Somaliland has detained unionist activists, which is bad, though once again it is a fiction that the Euro-Atlantic states don’t engage in these exact behaviors. It is clearly unreasonable to point to weaknesses in Somaliland’s democracy as an argument against recognition, especially given their region and continent and that they’ve had to work this all out without any outside assistance.

There is, however, one very important challenge to recognizing Somaliland: they don’t control the eastern part of their claimed territory, which was disputed and then lost in a recent conflict. A local unionist administration called SSC Khatumo has sprung up there and is seeking to become the 6th state of Somalia, a move strongly opposed by the Hargeisa government. This new administration is itself in a standoff with Puntland, which controls some of the territory. There isn’t an easy solution to this problem. Somaliland’s claims primarily rely on the 1960 borders of British Somaliland and thus become less strong if they seek independence as a different territorial unit. Somaliland also isn’t that large of a territory and they don’t seem inclined to give up any of it. Sometimes in such instances a plebiscite is held and the whole region is meant to go one way or another, but Somaliland doesn’t control that area to hold a referendum. Further, Somaliland doesn’t need to hold an independence plebiscite in the rest of the country. In the abstract, it would be ideal to hold an election in the eastern region with the options of union with Somaliland, Somalia, or independence, but it seems unlikely that any of the four “stakeholders” involved [including Puntland] would agree to holding such an election and abiding by the results. It isn’t impossible to recognize Somaliland while this dispute is ongoing, but there are significant drawbacks to doing so if there is not at least some sort of promising reconciliation process in place.

At the same time, this whole area is so conflict prone it doesn’t necessarily make a difference if Somaliland is recognized with its own, smaller breakaway province. Regarding other international matters, the Somalilanders are passionate about trying to obtain what is called the Haud from Ethiopia and some of them have the name in their Twitter handle to raise awareness of their claim. This plateau, of what we would call “badlands,” is sizable, and would represent a substantial addition to Somaliland’s territory. It was controlled by the British for a time but was ceded back to Ethiopia after World War II. While you or I would die trying to survive there, if you make a living off of camels the land is valuable. Objectively, it probably doesn’t matter very much if it is part of Somaliland, since like the nomadic herders they are, they already cross the border at will, but it is their traditional grazing lands so it isn’t strange they should want it to be part of their state.2

Somaliland and Ethiopia have cordial relations and seem unlikely to come to blows over this. They upset several regional stakeholders at the beginning of last year when they crafted a “Memorandum of Understanding” about land-locked Ethiopia leasing land from Somaliland to develop a port, ultimately in return for Ethiopia becoming the first country to recognize Somaliland. This fell through after Turkiye’s Erdogan, an increasingly important player in Horn affairs, brokered a reconciliation between Ethiopia and Somalia. This sequence of events is not that surprising if you are familiar with Ethiopian PM Abiy, who is known for making big deals on a handshake without doing any of the work necessary to make their implementation succeed. Regardless, Ethiopia is at serious risk of state collapse, and it would be prudent that any negotiations towards closer US-Somaliland ties involve receiving assurances from Somaliland that they won’t take any actions regarding the Haud region that may further destabilize Ethiopia.

So will Trump recognize Somaliland?

For starters, there isn’t a lot of evidence that the new Trump Administration is interested in Africa policy, and they’ve made no moves on it. The new Secretary of State Marco Rubio is yet to even take any calls or meetings relating to the continent:

Despite a relative lack of interest in Africa, Somaliland plays well with several things about Trump’s priorities and personality, including simply sticking it to the Somalians living in America who are politically associated with the leftist Ilhan Omar. More importantly though, Trump already withdrew troops from Somalia at the end of his last term [they were returned by Biden] and has paused new foreign aid spending to reassess its value [though how serious this is remains unclear.] Trump is also an old guy who likes the physical economy and big things, and will by extension find the premise of using Somaliland to guard the shipping lanes compelling. Further, he loves to be praised, and one can imagine his joy if there was a Trump statue like the one of Bill Clinton in Kosovo, but this time facing every ship which passes through the Red Sea and Suez Canal. Perhaps in time there would even be big, beautiful hotels overlooking the Gulf of Aden.

Recognizing Somaliland also allows Trump to stand up and say he was able to make the deal other people were too cowardly to make and that he has put America’s interests first instead of being restrained by the dead-end policies promoted by a bunch of haters and losers. Much is made over Trump’s “transactional” approach to foreign policy, which is a shitlib euphemism for saying he doesn’t make people suffer through a bunch of euphemisms and platitudes but instead makes deals with a clear recognition of interests. Somaliland’s government is open to playing ball. Somaliland’s Foreign Minister, Abdirahman Dahir Adan, sees things similarly, telling the BBC, “If the deal is good for us, we will take it. If the US wants a military base here we will give it to them.” I am personally in favor of ending the American Empire and not building any new bases, but given the collapse of Franco-American influence in the Sahel, the inability to protect the Red Sea from the Houthis, Iran’s missiles flying across the Middle East, Somalia’s inability to get its shit together, and, indeed, China moving in on Djibouti, from a “Grand Strategy” perspective, taking the opportunity to develop a naval base in Somaliland that has very few external costs but great utility is a can’t miss. I should add that, despite the fact that I am skeptical of Anglo-American global power, one of the genuinely good things about the post-WW2 global order has been almost complete freedom of commercial shipping, an interest which is greatly served by the US setting up shop in Somaliland. Unlike Somalia, the United States would not have to do domestic security work to maintain a presence in Somaliland, while in terms of protection from state actors, the presence of a US base would provide a large security umbrella for Somaliland, so it’s not a bad deal of anyone, and of course American personnel have US dollars they spend.

Still, I remain skeptical that the Trump Administration will choose to recognize Somaliland. However, at the same time I am confident that the One Somalia policy is dead, for now at least. With the Foreign Policy Committee steering the country towards engagement and the Republican Africa people already having close contacts with Somaliland, it seems sure that cooperation will increase. The United States has a long history of working with various groups that are not recognized as official governments, and there is no reason that Somaliland must be different. If Trump does move toward recognizing Somaliland, I suspect it will be some time into his Administration, when he has taken care of the issues with a higher priority. This is especially true as Trump clearly wants to be a domestic policy President.

There is another question that it is not entirely clear if the Somalilanders have stopped to ask themselves: will international recognition make Somaliland any better? Besides pride, an important human motivator, this is an open question. Has Somaliland had its success in spite of its isolation, or because of it?

Somaliland is very poor, and it does seem that recognition could improve trade. The only direct trade between the US and Somaliland I have ever personally heard of is that the multi-level marketing essential oil company doTERRA sourced frankincense from there, something which made the news when there was a report from The Fuller Project about abusive labor conditions for the women sorting frankincense resin [in doTERRA’s defense, it is not easy to send someone around to Somaliland to check on things.3] The Somalilanders would surely love to sell us camel products, though there isn’t much of a market for camel anything in America, but with some work maybe they could pioneer one. Regardless, increased markets for their goods would be one obvious advantage. Further, not having a recognized government to inspect your products and, indeed, your labor practices, can be a big challenge for setting up trade relationships.

In the bigger picture, it is not necessarily the case that international recognition would improve the lives of Somalilanders economically or politically. The experience of other countries has shown that foreign aid spending and other investment just tends to enrich and entrench a class of useless elites who are interested in little but putting on a show for for outside funders and distributing the money to their cronies. Ken Opalo, who writes the substack An African Perspective published a bleak picture of how the Western international system impacts Africa. Opalo is one of the most insightful writers on political economy of our time, and I suggest you read the whole thing, but I will go over key points:

Firstly, he makes the distressing point that being outside of the international system is the only reason that Somaliland derives its legitimacy from the people and relies on their support,

“To be blunt, achieving full sovereignty with de jure international recognition at this time would do little beyond incentivizing elite-level pursuit of sovereign rents at the expense of continued political and economic development. What has made Somaliland work is that its elites principally derive their legitimacy from their people, and not the international system…Just like in the rest of the Continent, the resulting separation of “suspended elites” from the socio-economic foundations of Somaliland society and inevitable policy extraversion would be catastrophic for Somalilanders.

The last thing the Horn needs is another Djibouti — a country whose low-ambition ruling elites are content with hawking their geostrategic location at throwaway prices while doing precious little to advance their citizens’ material well-being.”

I can’t emphasize strongly enough what a stunning indictment this provides of how the international system has doomed African countries. One difference about Somaliland is that they have already had a great deal of political development, whereas Djibouti is on its second President since its late independence [due to it having a strategic location and nothing else, France held Djibouti for around 20 years longer than the rest of its African empire.] Also, while Djibouti has the bizarre policy of letting anyone lease land for bases, the Somalilanders are specifically enthusiastic about getting involved with the Americans, which at least broadly has a clearer sense of purpose, though I question the wisdom of total alignment with American interests.

Opalo also criticizes the “fetishization of ritual electoralism and turnover,” which is to say the tendency to only care about elections happening but not about if democracy actually improves the lives of the public. However, I take some issue with Opalo’s criticism of Somaliland for only allowing three political parties at a time. How to set up political parties has been a constant challenge for Africa and one method of having one-party rule with elections is to allow such a proliferation of parties that none of them seriously challenge the ruling party [the Deby family in Chad are masters of holding real, but also fake, elections, and this is one of their techniques.] A further concern is that upon receiving recognition the Somaliland elite would see no reason to continue improving,

“It is not obvious to me how full recognition would resolve the many challenges currently faced by Somalilanders. To the contrary, it’s very likely that it would lock in these suboptimal elements of Somaliland’s political economy, or make them worse…nothing currently stops Somaliland and its international partners from making progress on the points highlighted above…That should be the focus of elites in Hargeisa, not a rush to recognition in search of sovereign rents.”

One of the greatest threats is that the outside powers want the veneer of democracy but are so obsessed with stability they don’t want elections to change anything, something I have repeatedly criticized about European governments. It is particularly important to note that Somaliland’s private sector is currently a major stakeholder in the government, but would be crowded out by the influx of foreign cash,

“Full sovereignty will blow up this balance by significantly strengthening the state vis-a-vis businesses, clan elders, and the general public. Flush with cash, focused on their narrow interests, as well as a strong preference for stability, foreign players will undoubtedly seek to attenuate democratic influences on the Somaliland state. You can already see this in the fetishization of electoralism, which deliberately ignores all the work that still needs to be done to strengthen democracy in Somaliland…

With foreign geopolitical attention will come an even deeper NGO-ization of Somaliland’s economic life and a severe case of policy extraversion. Uncoordinated and failing “development projects” will bloom. Hargeisa will crawl with “technical experts” out to dabble in the latest faddist trend. The cost of doing anything in the public sector will balloon beyond belief. Eventually, these new players will crowd out the influence on the state from Somaliland’s businesses, diaspora remittances, clan elders, and voters. There will be a lot of externally-facing “reforms,” but with little tangible benefit to Somaliland’s businesses or general public…

Somaliland is still a very poor country that must do all it can to avoid becoming an aid-dependent basket case that plays host to foreign geopolitical contests.”

It is perhaps an advantage of throwing in with America, that already having chosen a side they are less prone to having powers compete over them. Opalo is also concerned that the chaos coming from recognition would be greater than I imagine, and is right in his view that outside countries do not actually care about Somaliland,

“In the face of these likely upheavals, Somaliland’s international partners won’t have much to offer. When the rubber meets the road, they’ll do just enough to protect their interests and ignore the rest of the chaos. And when that fails they’ll cut and run.”

His solution is to condition Somaliland’s recognition on a series of internal reforms that work to ensure political and economic development. I don’t necessarily find this reasonable, especially as almost no African states meet the conditions that he describes. Opalo paints a dark but accurate picture of the impact that more outside influence may have on Somaliland. It is impossible to not think of the novel One Hundred Years of Solitude, where every contact with the outside world continues to make Macondo worse until it is destroyed. Somaliland is a small and poor country, and could rapidly become a Georgia-style laboratory for foreign influence destroyed by a pantsuit mafia if it comes into Western orbit. It is unlikely to happen under Trump, but these useless people with Master’s Degrees have no other marketable skills and will remain a menace for at least decades to come, and this is assuming the tide has actually been turned and fewer will be produced in the future. Still, in the famous words of H.L. Mencken, “Democracy is the theory that the common people know what they want and deserve to get it good and hard.” It is not reasonable to oppose Somaliland’s desire for international recognition on the grounds that we ourselves would ruin their country.

I can’t say if Trump will move towards recognition of Somaliland, but it seems that the failed One Somalia policy is over and there will be closer coordination between our governments than there was during the Biden Administration. The most responsible policy would be to make it clear that the United States wants to move that direction and to begin a series of conferences with other regional powers. The Mogadishu government lacks leverage over the United States and can either make some effort to come to an agreement or refuse the process entirely, but they provide us with nothing that we cannot get from Somaliland. The situation with the SSC Khatumo is more difficult, and we will have to discover what all parties, including Puntland, are willing to agree to. It is important, if possible, to avoid the situation of South Sudan, where the world’s newest state immediately falls into civil war. It should be noted that from an American perspective it doesn’t make a difference if that region joins with Somalia instead of being part of an internationally recognized Somaliland as long as the situation is stable, so Somaliland will have to decide what they may be willing to give up for recognition. The goal of recognition is to make Somaliland less, not more, isolated, so even if it is impossible to get the African Union and the East African Community on board it would be best to try and temper their opposition. It is ideal that more countries than just the United States recognize Somaliland, and Ethiopia, Kenya, and the United Arab Emirates can likely be brought on board. It is possible that the United Kingdom can be as well, with Somaliland being a former possession that might be willing to join the Commonwealth. There will be challenges, but there always are.

Ultimately, while there are strong legal and strategic reasons to recognize Somaliland’s independence, to me the biggest reason is simply that it is true. Somaliland has been an independent state for over 30 years with little outside help or sponsorship, and despite extreme poverty, has fulfilled the duties of a state better than most in sub-Saharan Africa. Joshua Meservey is right to say “Arguments premised on fictions are irretrievably broken.” There is no conceivable circumstance where the Federal Government of Somalia will take back control of Hargeisa. The United States’ Somalia policy has been based on fictions for too long, the biggest one being that the central government in Mogadishu will ever control the territory of internationally recognized Somalia. The arc of history runs long, and it seems Somalis will always inhabit their home on the Horn of Africa. Perhaps after a time of separation the Mogadishu and Hargeisa governments will find reasons to coordinate and grow closer, and ultimately the Somali people will all be together in a confederacy, but such a day is well beyond the horizon.

The truth is that US Africa policy has been an abysmal failure and Somaliland provides us with the only good opportunity to salvage what can be salvaged. The Trump Administration should embrace reality and move towards recognizing an independent Somaliland as Africa’s 55th state. Whether or not that makes Somaliland any better, only time can tell.

Thank you for reading! The Wayward Rabbler is written by Brad Pearce. If you enjoyed this content please subscribe and share. My main articles are free but paid subscriptions help me a huge amount. I also have a tip jar at Ko-Fi. I am a regular contributor at The Libertarian Institute. My Facebook page is The Wayward Rabbler. You can see my shitposting and serious commentary on Twitter @WaywardRabbler.

It should be added that while southern Somalia is appropriate for plantation agriculture, in terms of national environment, most of the Horn is more or less a wasteland, somewhat similar to Australia’s Outback. John Gunther memorably wrote of French Somaliland, “The temperature at Djibouti, an evil little city, can rise to 113 degrees when an evil hot wind called the Khamsin blows from the baked desert” [Inside Africa, 282.]

I’m sure as a people of camels, clans, and poetry, the history and mythology of how Somali clan grazing rights are established is fascinating from an anthropological perspective, but it is far out of my scope here to research it.

It is something of a coincidence this women’s rights group happened to discover this story, the woman was doing environmental reporting on frankincense overharvesting when she learned about it.

I congratulate any collective of people that can maintain a semblance of governance free from corruption and terrorism upon its own population. Based on this metric, as described, I pray that somaliland can continue to thrive and prosper, as with the rest of the world.

Good article. I have always been sympathetic to Somaliland and wrote about it back in July 2008. The 2008 article was slightly updated and cross-posted to Substack in 2023:

https://sharpfocusafrica.substack.com/p/republic-of-somaliland

My own view is that Trump doesn't care about Africa and I am okay with that. Whenever the US government takes a keen interest in our continent, it is often for the wrong reasons. I would rather Trump Administration ignores the continent than wreck it.

However, if Trump recognizes Somaliland then that would be a great thing indeed. At least, US recognition will deter Egypt and Turkey from trying to use the chaotic war zone called "Somalia" to destabilize Somaliland, which has done so much to build itself up