The Virgin Opposition vs. The Chad Regime

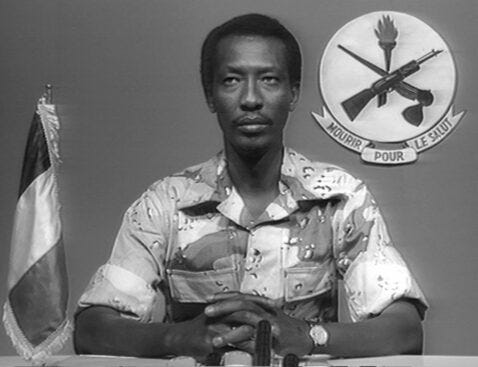

A Referendum in Chad Is Meant to Give Legitimacy to Mahamat Deby

“It must be taken as absolutely true that a corrupt city living under a prince can never regain its liberty, even if a prince and his entire family are done away with, indeed, even if one prince does away with the other, and without the creation of a new ruler, the city will never be at rest until the goodness of a single man, along with his exceptional ability, keeps it free.” - Machiavelli [Discourses, I.17]

The “transitional” government of the Sahelian nation of Chad is holding a referendum on Sunday, the 17th, which it claims is part of a process to move towards holding elections in 2024 and return to democratic government. The vote is on a new constitution which keeps the country fundamentally the same, though ostensibly devolves some amount of local control while maintaining a unitary state. Widespread political repression as well as the boycott by many opposition groups makes the poll’s outcome all but a foregone conclusion. It is, in fact, the turnout that most people are watching, not whether it passes or fails. Though many citizens think that the vast, diverse, and sparsely populated country should be made into a federation, this is not a good system for a despotic ruler. It is widely expected that Mahamat Deby, the son of long-time ruler Idriss Deby, will win any 2024 election and thus become the civilian ruler of a nominal democracy. Chad, one of the poorest countries in the world, is the last in the region allowing French troops, as the Debys are long-time clients of the French. The country is seen as being at a high risk of another coup, though it’s less clear if that would be against Deby or a “self-coup” where Deby throws out his Prime Minister, Saleh Kebzabo, who was a long-time opposition figure, and ends all pretexts of coming civilian rule. However, the French presence is increasingly unpopular among the public and Chad is surrounded by destabilizing conflicts on all sides, including in Sudan where Deby’s tacit support of the Rapid Support Forces is said to put him in a perilous position. While it is all but certain the referendum will pass, Mahamat Deby faces many challenges and it is not clear that he can hold power in this troubled country. At the same time, it is nearly impossible that any leader could bring Chad peace and freedom, much less prosperity.

Readers of this newsletter will already be aware of the volatile situation across the Sahel, where one can now drive across an area the width of Russia without entering a civilian-led government. Chad is in many ways similar to Niger, though more diverse, and with a greater history of French intervention and lesser history of free elections. Which of these two unfortunate countries is less developed or poorer depends on what year or methodology you look at, but the US-based extreme poverty NGO Concern USA listed Niger as the third poorest country in the world and Chad as the second in 2022 [nearby South Sudan takes the top spot.] According to the CIA Factbook, the plurality ethnicity, the Sara are just over 30% of the population, whereas the Deby’s Zaghawa tribe who have been politically dominant for decades are only around 1% of the population. It also needs to be noted that though the French were quite bad imperial overlords who never stopped looting Africa and intentionally kept it underdeveloped, Chad is a naturally poor country, remote and mostly semi-arid. It’s unlikely that without colonialism it would be much better off, though it certainly wouldn’t be a unified country.

Chad’s lack of development is astounding. To look on Google Maps, the great majority of the country shows no signs of habitation. Some statistics from the CIA Factbook are incredible: the country has never had railroads; there are 206 km of paved urban roads in the entire country which is three times the size of California [and only one paved highway outside of the capital N’Djamena]; Chad has more km of oil pipelines than paved roads, though the pipelines do connect to other countries and thus international terminals; only 3 registered commercial aircraft are based in the country of more than 18 million people; Chad has only 5,300 total telephone landlines, though 60% of people have some form of cell phone; 18% of the population uses the internet; there is one state-owned TV station and two private stations, while there is one state radio station and 10 private radio stations. Around 88% of the country ekes out a living from subsistence agriculture. In short, besides a few key trade items, the modern world has hardly reached much of the Chadian population.

In the late 1970’s, Libya, led by Colonel Gaddafi, invaded northern Chad, nominally in support of a rebel group, the continuation of a pattern that had been going on for over a decade. French interventions saved the country, with the last phase of the conflict, known as the “Toyota War” of 1987, having been a resounding victory for Chad. It was in this conflict that an officer named Idriss Deby, who had taken part in the 1982 coup which brought warlord Hissene Hibre to power, rose to prominence in the Chadian military. After occupying a top position for a few years, the paranoid Hibre turned against Deby, accusing him of plotting a coup. Deby fled to Darfur in Sudan, where there are many members of his Zaghawa tribe. He formed a rebel group, made a deal with Gaddafi, and invaded Chad, allegedly with Libyan and Sudanese support. Hibre fled and Deby took power without real resistance. It’s not clear if Deby had been plotting a coup all along, though this is a common pattern in history where some person is accused of plotting a coup and then ultimately does it only after being exiled. It is perhaps the origin of the proverb, “keep your friends close but keep your enemies closer.” Hibre should have.

Upon taking power, Idriss Deby quickly worked to move Chad towards some form of democracy. Initially, after a three month transition, it was his own party that gave him formal power, but they continued to work towards a de jure pluralistic state. In reality, Deby’s power was as such that there would never be fair elections, even though opposition parties were always allowed. He was never shy about using the force of government to maintain his own power, though he kept a veneer of democracy. Opposition parties were regularly harassed and their rallies were broken up, while the regime controlled the most powerful media. At the same time, this Saleh Kebzabo who is currently the PM ran against Deby four times and was never killed or exiled, though he was periodically arrested or otherwise harassed by state security forces. It’s perhaps fair to say that the man was what they call “controlled opposition,” but many regimes do not even allow that. Throughout the years, Deby changed Chad’s constitution multiple times to get around term limits, ultimately staying in power for 30 years. The Idriss Deby regime is perhaps one of the best case studies in fake democracy, especially given that he did go through the motions, whereas some despots maintain a “transitional” government for decades. Even with good intentions it is nearly impossible to conduct a proper election in an enormous country with dismal communication infrastructure and extremely low education levels, and on top of that Deby always ensured there wasn’t a level playing field.

Throughout the elder Deby’s reign, as with the rest of Chad’s post-colonial history [which he was in power for half of,] there was constant conflict and frequent coup attempts. It was particularly tenuous for him to consolidate power the first two years, but he was able to with the help of men from his tribe who were placed in high level military positions. When oil came online in the early 2000’s, it did little to develop Chad but did give him crucial hard currency to fund his military. He stayed close to France and to a lesser extent the United States, both of whom had an interest in using him as a hedge against the neighboring dictators Gaddafi in Libya and Omar Bashir in Sudan, and later, in their regional counter-terror operations. His rule was threatened by the conflict in Darfur, where his Zaghawa tribe had helped to start the insurrection, and they, as well as the related Masalit tribe, faced ethnic cleansing at the hands of militias mostly made up of nomads from tribes known as Chadian Arabs. There were various rebellions throughout the country, including rebels reaching the capital, but with French support, Deby managed to hold power every time. Things dragged on this way for a number of years, a desperately poor and violent client state surviving by the support of an outside power and the sheer experience of its military, until Deby again changed the constitution in 2016 to stay in office. This time, a group of former officers defected, and calling the Front for Change and Concord in Chad [FACT, the acronym makes more sense knowing the county is called Tchad in French] started yet another rebellion against Deby.

The FACT rebellion went on until 2021, when Deby was killed by rebels while commanding troops on the front lines. Though I can’t find the next most recent example, this makes him the first Head of State killed in combat in a very long time. One BBC correspondent wrote of Deby’s death,

“Idriss Déby was known as that rare thing - a true warrior president. The former rebel and trained pilot was the opposite of an armchair general.

For 30 years, he clung to power in Chad - a vast nation that straddles the Sahara and is surrounded by some of the continent's most protracted conflicts.

And Déby had a hand in every one of them - from Darfur to Libya, Mali, Nigeria and the Central African Republic. His troops were among the most battle-hardened on the planet.”

On the day that Deby was shot it had just been announced that preliminary results showed he had “won” a 6th term with almost 80% of the vote. Though there were constitutional provisions in place for fulfilling a vacancy in the Presidency, in the day between being shot and succumbing to his injuries, he [allegedly] produced a document naming a Military Transitional Council of 15 people, led by his son Mahamat Deby, a Four-Star General. This was widely viewed as a coup, and Mahamat certainly took the normal actions of a fresh coup government, such as imposing a nationwide curfew, shutting down the internet, and cracking down on opposition. However, French President Emmanuel Macron traveled to Chad for Idriss Deby’s funeral and pledged French support for Mahamat Deby’s rule, causing the rest of the “International Community” to go along, since France is seen as Chad’s suzerain.

There was a great deal of concern about the younger Deby’s ability to hold Chad together, but he possesses the old man’s acumen. Like his father, Mahamat spoke of democracy and said he had no plans for sole rule, initially putting in place an 18 month plan for a transition. In the time since the Military Transition Council took power in Chad, coups have accelerated all over the region, overthrowing the governments of Mali, Guinea, Sudan, Burkina Faso, and Niger. In fact, Mahamat Deby is one of the only rulers to have maintained power since April of 2021. At the same time, radical Islamic terrorism continues to spread while instability and poverty in the Sahel only get worse. In October of 2022, to no one’s surprise, Deby announced an extension of the transition period. This led to a large protests, and to the massacre of protesters by Deby’s troops, an event which came to be known as “Black Thursday.” The government acknowledges 50 deaths, whereas others say around 300 people died. Further, Many were arrested for their involvement, showing the authoritarian bent of the new ruler.

In April of 2023 war broke out in Sudan, between the two generals who had been running the junta in that country. At the same time, France was being kicked out by hostile coup governments in Mali and Burkina Faso, causing them to put ever more pressure on Niger, the last elected civilian government in the region, which fell in July of 2023. Mahamat Deby was left as France’s sole ally in the Sahel, in the ruins of Macron’s failed Africa policy. Deby is stuck between a reliance on outside support and a wave of anti-French sentiment- which now includes Chad’s civil society groups and opposition demanding France leaves the country this year. What’s more, refugees are pouring into the impoverished country from Sudan, and those refugees are primarily from the Masalit tribe, related to Deby’s Zaghawa tribe who make up military leadership. All of this while Deby is allegedly letting the United Arab Emirates use the country in support of the Rapid Support Forces who are accused of committing genocide against the African tribes. There is a widespread belief that this is causing him problems among the military elites, however I think this underestimates the cynicism of elite minorities who take power through patronage. They have been a ruling caste for decades, and would want to take Deby’s position for the power itself, not to help distant kinsmen. However, infighting amongst such a small ruling minority has a great potential of causing them all to fall, especially given that Chadian Arabs are a much larger group in the country. There is also concern that the Sudanese General Hemedti, himself of the nomadic Arab tribes, will get chased into Chad if he loses in Sudan, and perhaps even try to seize the country. The former is entirely possible, and they certainly don’t want that large gang of rebels setting up shop within their borders, but the latter is simply a matter of believing Sudanese Armed Forces’ propaganda, which portrays Hemedti as a “foreigner” due to his Chadian Arab heritage. [It needs to be noted that for the time being the RSF is winning Sudan’s war, so Hemedti is unlikely to be chased into Chad.]

Mahamat Deby has overcome many challenges since taking power and Chad has remained a strange beacon of relative stability in the Sahel. Perhaps some of this can be attributed to the outside powers having the sense to value stability over democracy in this instance, but now what Deby needs is to formalize his rule. This is where the referendum of December 17th comes in. Much of the country and most of the opposition groups want a federal system, but that isn’t what they’re voting on. This is simply a yes/no vote on a Constitution that Deby and his “National Transitional Council” [which replaced the Military Transitional Council] have put forward. This constitution would increase local control while maintaining a unitary state, but basically create councils that would deal with some local issues while not having federal representation. It needs to be noted that Chad’s previous constitution did not fail, the President simply died and then they didn’t follow its succession procedures, so there isn’t any upfront justification for holding this referendum. However, it is clear that Deby is testing his support and trying to convince the public to buy into his government in preparation for running in a non-competitive election in 2024.

Deby has made several moves in preparation for the referendum. Perhaps most notable, the government granted amnesty for “Black Tuesday.” This was framed as “reconciliation” but it is somewhat nefarious when you consider that it equalizes people persecuted for non-violent protest with soldiers and police who gunned down non-violent protesters, as all of them are receiving amnesty together. He also came to an agreement for the opposition leader Succes Masra, who leads the party “The Transformers” which organized the Black Tuesday protests, to come back to the country. This was disappointing to some of his supporters, as he was seen as one of the only major opposition leaders who wouldn’t compromise with the regime. Despite seeking a form of peace with the opposition, there has also been a closing of media spaces such as political talk shows and the full power of the state is clearly behind the “Yes” vote. This all continues a sort of push and pull that Mahamat learned from his father, of allowing some political expression while trying to prevent it from becoming powerful enough to be a problem, while also knowing that to rule Chad is to always be fighting.

With an enormous number of weak opposition parties- over 200 as of 2018- and those split between “no” and boycotting, there is no question of the referendum passing. The bigger question is both if the act of holding the vote causes instability or brings about any other drastic actions, and if enough people turn out to make it appear legitimate. As of the 15th, two days before the election, it was reported that the government had stated that a majority of eligible voters had not picked up the voter cards they would need to show at the polls in order to vote. This is a bad sign for Deby, as a turnout of around 50% or lower will be a clear sign his new constitution lacks legitimacy. Further, it is harder to fake that people voted than to fraudulently report how they voted, since the citizens can see how many people are out going to the polls. Unless there is a coup- either a palace coup against Mahamat or his own coup against the transitional government he set up- or a genuine popular uprising, it seems one way or another this transition process will continue along, though there is no reason to believe it will lead to any sort of free government.

For myself, I am bullish on Deby’s prospects. He has already survived a lot and done an impressive job of bringing back in those who can be worked with. I harbor no illusions that he will turn Chad into a free and prosperous pluralist democracy, but incredibly Chad is currently one of the better places to live in the entire region. The villagers are not constantly being slaughtered by crazed hordes of terrorists and there aren’t two warring generals running rampant across the country, which is relatively good by 2023 Sahel standards [four of the six countries bordering Chad have a Level 4 “Do Not Travel” rating from the US State Department, whereas Chad is a 3, “Reconsider Travel.”] Most of the reasons that people expected Deby to suffer a coup have already passed, but holding such a referendum exposes a regime to a lot of volatility. He is certainly at a much higher coup risk than the government of Norway, but there seem to be some misunderstandings about how power works from the people who expect Deby to fall. For a large sparsely populated country governed by a small warrior elite, “civil society” groups and weak opposition parties are unlikely to topple an established ruler, whereas a palace coup creates infighting among that elite which weakens all of them and anyhow it was the military insiders who helped him take power on his father’s death. It doesn’t make sense to risk taking a shot at him when they can maintain their comfortable ruling class positions. Further, by moving forward to formalize his rule, he strengthens the support of his French Praetorian guard, who are more than happy to play along. He seems to have a good eye for risk, and thus a good chance of surviving any coup attempt.

Chad remains a fragile state and perhaps will always be a poor and oppressive one with violence on the exterior. The odds of any great leader coming along and bringing the nation freedom and prosperity are minimal. However, that doesn’t mean that it can’t go on like this, and at least not get much worse. While Africa needs genuine development and shouldn’t be cynically used as a chess piece, in this instance security is of primary importance: Chad is the only thing stopping a vast region from utter chaos and the creation of a corridor of lawlessness, terrorism, and weapon and human trafficking the size of Siberia from opening up in northern Africa. It makes sense for France to support Deby’s continued rule. Of course, the people of Chad want what anyone else does, which is to lead secure and comfortable lives without undue oppression, but liberal democracy doesn’t work in a country at this level of social and economic development. Not having the wars of Sudan and Libya or the extreme terrorism Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso consume the country is all that can be hoped for at this time. I fear that Mahamat Deby could only possibly be replaced by someone more avaricious, more brutal, and less competent. It seems for the best that his scheme to create a facade of legitimacy is successful, as the people of Chad can then at least survive.

Thank you for reading! The Wayward Rabbler is written by Brad Pearce. If you enjoyed this content please subscribe and share. My main articles will always be free but paid subscriptions help me a huge amount. I have a tip jar at Ko-Fi where generous patrons can donate in $5 increments. I am now writing regularly for The Libertarian Institute. Join my Telegram channel The Wayward Rabbler. My Facebook page is The Wayward Rabbler. You can see my shitposting and serious commentary on Twitter @WaywardRabbler.

Nice write up, thanks.