We Don't Even Know What A King Is

In the "No Kings" Discourse, American Ignorance Again Takes Center Stage

“Even though the kings lost their empire for the reasons and in the ways already discussed, those who drove them out, having immediately established two consuls who took the place of the kings, nevertheless drove out of Rome only the title of king and not kingly power.”

- Machiavelli [Discourses on Livy, I.2]

On Saturday, October 18th viewership of re-runs of Matlock dropped precipitously as very old people- and a smattering of younger people with roughly similar life expectancies- got out of the house for a second round of “No Kings” protests, whatever that is supposed to mean. The legacy media are calling them the largest protests in American history, which I suppose is fairly easy to achieve when the core demographic has nowhere else to be. It was nice that these geriatrics and shut-ins got out of the house for an afternoon to stand around with irrelevant signs and express their support for Mandarins over the court eunuchs. Lest anyone think I am genuinely feigning obtuseness [a rhetorical technique I despise] I obviously do get the idea that in their minds- which are past their peak due to age and were never that impressive- they think this is the best way to speak against Trump’s penchant for arbitrarily using power and express their fear that the tendency will increase. It’s also probably the case that some marketing person felt they had overused “tyrant,” “dictator” and “literally Hitler” to the extent that they needed to come up with something fresher and more patriotic, and I don’t disagree, though king was not the thing to land on. Nevertheless they are pleased with themselves. Amusingly, they did have to change the name at demonstrations they conducted in monarchies for clarity:

The funny thing about this is that king and tyrant are not at all synonymous in political theory or in practice, though I must admit that I find it hard to argue with Hobbes’ point that you can’t give the same type of government different names based simply on whether or not you like it. Regardless, to anyone with with perfunctory knowledge the word “king” does not imply “tyrant.” Most kings have thoroughly limited power and there is in fact only one European king in the modern era who ever tried to be a dictator [Alexander of Yugoslavia.] It must be mentioned that the “dictator” was itself a crucial and generally positive Roman political concept which happened to grow in popularity as a negative term in the 19th and 20th centuries. Even if we did have a government small enough to fit in the US Constitution, the role of the President is much more powerful than the typical king and also by design fills the function of a king. The reality is that [so long as one has a government at all] a king is broadly neutral to liberty and based on organizations that rate such things, monarchies are doing better on average than republics in that regard.

Even with 37 years of living here to get used to it, I am again astounded by the ignorance my countrymen both sides have shown of this topic, to the extent that I have been driven to try to explain the history and diverse aspects of monarchy here. First, though, let me show you some local protesters and then go over go over some of the discourse.

This video is near me. I believe in Moscow, Idaho but don’t remember. While I don’t think they are causing any harm and do support their right to protest, it’s incredible that the media seems to genuinely believe the Trump Administration and his supporters are threatened by such people gathering:

It’s been commented that this is similar to the Tea Party protests of 2010 but it seems like an even more fake and gay version, and these people are older and have even less clear goals. The big thing is these are pro-establishment protests…yes the Republicans are in power and thus are the “establishment” now in that sense but the overall gist here is they want to save the power of the bureaucracy so that things to remain the same as they have been for decades. In general, to the extent protests are ever effective, short of outright overthrowing a regime, it is for one of two reasons: either they see that these young people are the future and want them to feel they have a stake in society and thus try to come to some sort of settlement, or the people in charge are simply scared you will vote against them. Old people who always vote Democrat and who have voted against Trump 3 times [who, as far as we know, has no future elections] have no leverage whatsoever just by showing their numbers and by the average age alone show their weakness. This is all the more true as they don’t have a clear policy message, they just want “HR Department Government” instead of “Boss Government” [the true ideological struggle of our era, history being a farce this time.]

Anyway, here is the type of discourse we are getting:

The more common thing that though has been the constant din of “In countries with a king you wouldn’t be allowed to have a ‘No Kings’ protest!” This includes people saying things like “Your head wouldn’t stay attached to your neck.” I can assure you that in Kingdoms of Sweden, Belgium, or Britain you are more likely to be beheaded by an Islamist than you are by the King for peacefully protesting against the monarchy or anything else: this is a statistical fact. There is little appetite for republicanism in most such states because their resident monarchs are the least of their problems, but Australia has a fairly robust Republican movement, which operates freely and is entirely lawful. In the UK itself, one can go to a Republican organization’s website and buy merchandise saying things like “Down with the Crown,” “Not My King” and “Abolish the Monarchy.”

I need to make it clear I am not just picking on random people. Here is the Speaker of the House Mike Johnson making this same claim when he definitely does or should know better:

I can see that for Americans I need to go quite far back here because we are a nation of know-nothings, except that unlike a Russian, who Tolstoy says, “is self-assured precisely because he does not know anything and does not want to know anything because he does not believe it possible to know anything fully” [War and Peace, III.I.X] the American is self-assured because he knows nothing and has absolutely no idea that he knows nothing and is convinced not just in the possibility but in the ease of knowing things fully. And thus, as a nation we are all agreeing that a king would chop your head off for protesting, the only disagreement is Republicans saying “see, Trump isn’t doing that, so he isn’t a king,” and Democrats saying, “Our point is obviously that he wants to consolidate power until he is a king at which point he would do that.” In this particular instance, I don’t think either side is being intentionally obtuse: I think the obtuseness is genuine. As long as we’re here, I regret to inform you the libertarians are also in on it:

The one exception I have seen is from my friend David Dennison. I don’t really agree with his overall thesis but he is the only American I have seen try to explain what a king is to his own small segment of Americans:

David knows this from the fact that he lives abroad and thus actually knows what its like living in a monarchy; I am not one of these people who thinks living abroad generally makes you any more wise [he isn’t either] but in this specific instance it did lead to him understanding the situation.

A grand irony in all of this is that it is the liberals who believe in none of the significant aspects of religion, nor in the value of classic texts, of traditional art, of objective beauty and the like who have the deepest spiritual need for a king. They treat the government with religious veneration and are obsessed with its liturgy. It is Trump’s comportment and iconoclasm that are his cardinal sins to them, because they have systematically torn down everything that makes life meaningful and have nothing left to venerate but petty traditions of government that have no relation to public well-being or liberty. They are desperate for a figurehead who never changes anything but acts in a way which they can approve and who makes them feel that life has some meaning.

Anyway, clearly, I need to start really at the beginning here. I have previously written an article explaining some of this which you can peruse if you are so inclined, but I believe what follows the link will be adequate.

A Brief Introduction to Classical Political Theory

“In your old states you possessed that variety of parts corresponding with the various descriptions of which your community happily composed; you had all that combination, and all that opposition of interests, you had that action and counteraction which, in the natural and in the political world, from reciprocal struggle of discordant powers, draws out …

This is the basic story of a how a government works: a commonwealth is founded among men to deal with common issues collectively. At the most primitive level this arises when particularly powerful chieftain’s authority is recognized by his tribe. This is the beginning of the “cycle of constitutions,” most thoroughly described by Polybius in Histories Book VI 3-10, though the concept dates back to Plato’s Republic Book VIII and is more succinctly described by Aristotle at 1286b in Politics. It goes like this: the chieftain develops legitimacy over time and becomes a king, a title which is passed onto his heir because more complex political organizing did not exist, though in some instances the tribesman vote on his heir [generally for a member of the prior chief’s family regardless.] Ultimately the kings become corrupt and wicked and are overthrown or greatly reduced in power by the upper order of society; those noble members concentrate wealth and become a corrupt oligarchy; the people overthrow them but then growing used to living in freedom and never experiencing tyranny they stop being jealous of their own liberty; the whole thing devolves into mob-rule, which Polybius calls Ochlocracy, at which point a strong man inevitably takes power to bring order and you start over again.

In a rare defense of the Democrats, I will say that to some extent they have sussed out where we are in this cycle and recognize the risk of mob rule and havoc bringing the tyranny of one man, though they certainly didn’t see it when they were encouraging or at least defending the 2020 Mostly Peaceful riots, which did much to accelerate the cycle.

Any of these forms of government are by themselves are highly unstable and the cycle will move quickly. For starters, tyranny is really hard to manage, relying more on popular consent than is commonly imagined. There is a reason that many of the most notorious tyrannical regimes centered on one man were very short, or at least had a very short period of peak tyranny. The art of successful statesmanship is to use the lightest touch possible while still achieving necessary and desirable goals, which the political theorists generally called “moderate government.” Both ideology and wickedness are opponents of good governance for this reason and contribute to regime instability. It is overall due to weakness and foolishness that men choose tyranny. Machiavelli writes,

“In the end almost all men, deceived by a false good and a false glory, allow themselves, either willingly or through ignorance, to pass into the ranks of those who deserve more blame than praise, and having the capacity to create, to their everlasting honour, either a republic or a kingdom, they turn to tyranny, failing to realize how much fame, how much glory, how much honour, security, tranquillity, and peace of mind they are losing through this choice, and how much infamy, disgrace, blame, danger, and anxiety they incur.” [Discourses, I.10]

The other sources of power within a state are the upper and lower orders. However, a government by the upper orders rapidly becomes oppressive as they take control of all of the land and the resources, while government by the lower orders rapidly devolves into mass looting and violence. Athens is the only famous somewhat positive example of an almost entirely democratic system, and the Golden Age of Athens was like a desert bloom after an inundation: a brief flash of glory. The Golden Age of Athens lasted around the lifetime of a man, but did leave a legacy for the ages. Even so, it was dominated by Pericles as a popular ruler through much of that period so as good as had an elected head of state in charge of everything, though sovereignty lied with the people.

Machiavelli notes that the two tendencies of an upper and lower order exist in every republic, but that the lower orders are overall more fit to safeguard liberty, since “we shall see in the former a strong desire to dominate and in the latter only the desire not to be dominated, and, as a consequence, a stronger will to live in liberty” [I.5]. Commonly, it is believed that the conflict between these two leads to the demise of the state, which it can. However, Machiavelli’s main innovation is recognizing the value of such disturbances in a state, writing, “Those who condemn the disturbances between the nobles and the plebeians condemn those very things that were the primary cause of Roman liberty…all laws passed in favour of liberty are born from the rift between the two” [1.4]. In short, after public disturbances, a settlement is hopefully reached which protects the public from the depredations which caused the disturbances. The reason none of these pure forms of government work are fairly obvious in the first two: a king will have a tendency towards tyranny and also lacks the numbers, and thus for any large political body will have to raise funds for and deploy endless armed thugs to keep control. If the aristocracy has all the power they will simply accrue endless wealth and power and become an ever more corrupt oligarchy while the peasants starve.

It is less apparent why the commons can’t have the all power- in our era where many states prefer at least the appearance of such- but the commons have a constant need for money and credit, and thus are inevitably bought off by money lenders if there is not an upper order of land owners as well as a Prince who with any luck is willing to tangle with financial interests. Further, the commons have a tendency towards looting the means of production without putting it towards productive use. The troubles of post-independence Africa, which are myriad, are commonly attributed to race by racists and to racism by anti-racists, but are what political theorists tell us are the inevitable results of a complete takeover by the masses. This change in political power leads to the large and economically productive estates being carved up by people who lack the skills or capital to manage them and then revert to subsistence farming and people get poorer if they don’t starve outright and everything reverts to government by brute force [there is no good solution to the problem of severely unequal land ownership, Livy called agrarian laws the “customary poisonous brew” of the Tribunes [II.52], and it was ultimately a major factor in the fall of the Roman Republic.]

The solution to the severe problems of pure government is mixed government which combines all of these elements, an idea Machiavelli bizarrely takes credit for recognizing despite that it is clearly laid out in Aristotle. In Rome, after the Kings were driven out the Senate took power [Senate simply means “Old Men.”] They put two consuls in power for a year at a time, realizing that it is not in and of itself power which corrupts but power wrongfully seized and power plus time [and in fact, the dictatorship, a temporary emergency position, saved the Roman Republic many times, as Machiavelli describes at I.34]. However, as the city grew, the Senators and the Consuls from which they were drawn from concentrated wealth and became increasingly oppressive, and public disturbances gave rise to Tribunes, men who were chosen by popular assent and whose job it was to speak for the public.1 The power and number of the Tribunes varied over time, but primarily they were allowed to propose or veto legislation voted on by popular assent, as well as interceding on behalf of citizens who were being prosecuted by a magistrate and judging the legality of the prosecution.

This is the basis of the modern system of a bicameral legislature and a king or president. It is hard to say to what extent something like this is the natural order, because every modern state of any size in the world has political heritage from institutions of Ancient Rome. However, it is generally the case that in any society with a bit of complexity you end up with a situation where someone is at the top, there is a wealthy group who meet together and in various ways advise and provide funding to that individual, and the people of the lowest orders meet together in the village square and have someone responsible for speaking to the Lord. Of course, the balance of power between them varies. Further, human affairs are always in motion, so the balance changes. Mixed government does not arrest the cycle of constitutions, it simply slows it and makes it less violent that society may develop and grow prosperous in between various changes, and hopefully some generations can have good lives of peace, prosperity, and liberty.

A key element here before moving on is delegation. Even in the most oppressive state such as North Korea2 where we think of the legislature as “fake” it in fact it still has a great role in running the state simply because there is plenty of day-to-day work to be done. Variations of this exist across any sort of political body but no man controls everything in a state. For example, the Persian Empire was run by Satraps, who were themselves basically kings of the domain the King of Kings had assigned them. Delegation is necessary to run anything large, and the power of the top monarch could vary drastically, but was often much less than is commonly imagined. For example, in Japan for several hundreds of years the Emperor, despite being a deity to his people, had no political power whatsoever. In both Japan and China the Emperor was largely a prisoner in an Imperial Palace at various times, yet still was considered to himself be the state. In times of low levels of political development, kings were commonly nearly broke and struggled to get their vassals to provide them with money or troops. Victor Hugo memorably describes in Notre Dame de Paris how in the late 15th century the city was a patchwork of fiefdoms and the king lacked the power to set basic regulations in Paris such as to let cargo pass freely through the city, keep store fronts lit at night, or remove waste [for this same reason, he explains in Les Miserablés how into the 19th century the sewers weren’t even properly mapped.] Pharaohs somehow managed to maintain immense power, and Louis XV ultimately got rid of the powerful post of Chief Minister and governed directly, but these are historical exceptions which still involved substantial delegation. In general, where a king had direct control was in his demesne, which is to say the lands where he is the prince, duke, or count [being the Duke of Lancaster and Cornwall appears to remain the main source of private income for British Monarchs, though their tax and disclosure status is always controversial.] As far as I know, this is why Prince is the preferred nomenclature in political theory when discussing a monarch, though I’ve never seen that directly stated.

This all brings us to our founding, the American colonies which were sent out from a monarchy and which became successful beyond anyone’s dreams. Government arose organically within these colonies. As much as there is a tendency to say that “Americans didn’t want to pay taxes” the reality is that Parliament, followed by King George III, got into an unnecessary dispute trying to infringe on the traditional rights of these English subjects. The colony governments in fact produced money they were asked for through internal taxation but bristled at direct levies and the situation escalated.3 The colonists were well-educated, profoundly interested in Livy’s history and books on law, with Edmund Burke claiming that he spoke to an eminent bookseller who said that outside of books of tracts on popular devotion he has not exported more books on Law than anything to “the Plantations.” Burke further claims that nearly as many copies of Blackstone’s Commentaries were sold in America as in England [Speech of Conciliation with America.] The Colonies had about 1/3rd the population or less and were less urbanized and more lightly governed and thus with fewer causes for legal disputes, so this shows an extraordinary interest in the Law as a topic of personal study.

Almost all of the causes to which the British used at the time to justify the war were nonsense- for example, smuggling did not occur in America at any greater rate than in England and was prosecuted where discovered. This really was a legal dispute that got out of control as Parliament and the King foolishly tried to demonstrate their previously unchallenged supremacy for its own sake, even though they were losing massive amounts of revenue in an ill-fated attempt to prove they could collect it from consumers in America instead of merchants in England. The wrongheadedness of the English government and the principled steadfastness of the American colonists who were jealous of the liberty which was traditionally afforded to them as English subjects was the root cause of the war.

Despite what Americans want you to believe now, the American Revolution never had an ideological opposition to monarchy as a key cause. It’s true that Thomas Paine’s Common Sense, released at the beginning of 1776, was amazingly widely read [it remains the best selling American book in history] and is strongly anti-monarchist, but Paine was a radical and was a much better pamphleteer than political theorist. In short, its impact was most of all getting men in the street and under arms and encouraging the public to support declaring independence, but it was less influential on the ideology of the revolution, particularly among the upper order of Americans who were the revolution’s leaders. It’s important to look at the actual text of the Declaration of Independence, which reads,

“In every stage of these Oppressions We have Petitioned for Redress in the most humble terms: Our repeated Petitions have been answered only by repeated injury. A Prince, whose character is thus marked by every act which may define a Tyrant, is unfit to be the ruler of a free people.”

The language which all these men signed is that a Prince of this particular character is unfit to be the ruler of a free people, not that monarchy itself is an unfit system to rule a free people. If at any point up to that he would have came to terms they would have kept the the Monarchy. Commonwealth status like Canada has now without a widespread war would have been a dream to most men who ultimately turned to revolution and republicanism.

Burke, writing in 1777 and still promoting sensibility and conciliation, said,

“I have always wished, that as the dispute had its apparent origin from things done in Parliament, and as the acts passed there had provoked the war, that the foundations of peace should be laid in Parliament also. I have been astonished to find, that those whose zeal for the dignity of our body was so hot, as to light up the flames of civil war, should even publickly declare, that these points ought to be wholly left to the Crown. Poorly as I may be thought affected to the authority of Parliament, I shall never admit that our constitutional rights can ever become a matter of ministerial negociation.” [Letter to the Sheriffs of Bristol]

The two core points here are that the root of this dispute was in fact between the colonies and Parliament- the democratic part of the British state- and that Parliament ultimately let the King surpass what should have been his authority, because such things happen periodically in any system.

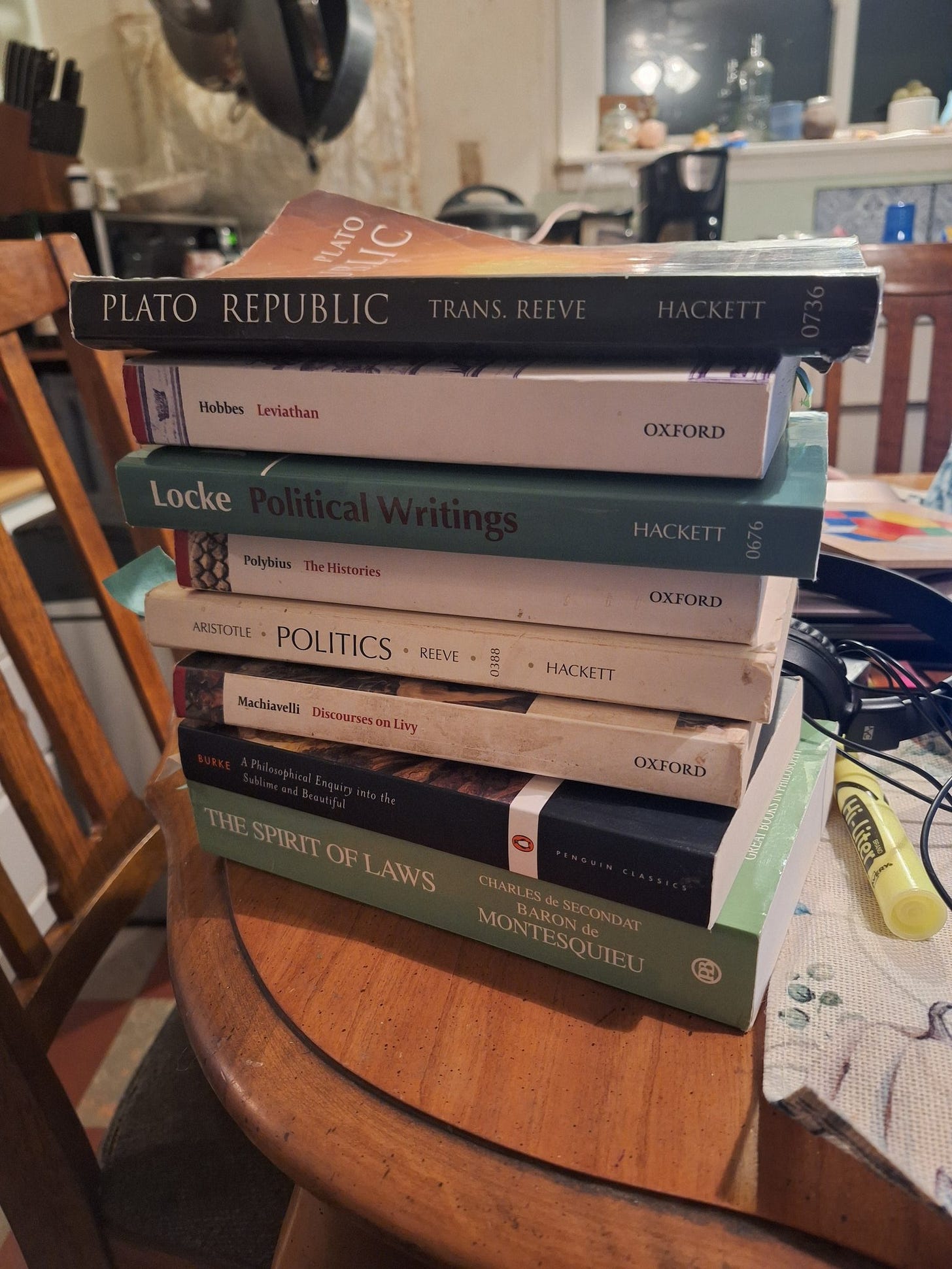

Once it became obvious that the Crown and Parliament were intransigent and independence was declared, the newly independent United States of America did attempt a government with no meaningful role of Prince. The Articles of the Confederation carried them through the Revolution, in no small part because Parliament, the ones who actually have to collect taxes and get re-elected, grew weary of supporting what came to be seen as the King’s war. However, the Articles of the Confederation, which did not form a proper single Republic, were seen as lacking sufficient strength of action. There was much debate around this but ultimately our great lawgiver James Madison was assigned to write a new Constitution. He produced a wiser and more thorough document than the Articles of the Confederation which had to be put together rapidly to serve as a provisional government to prosecute and fund the war. It is said that Madison consulted over 80 texts when writing the Constitution, though if there is a list, I have never found it. He was most of all influenced by the Roman Republic and the 18th century French political theorist Montesquieu.4

Madison was a profoundly wise man who overall did a very good job, and he recognized clearly the necessity of implementing a Roman system of mixed government. Thus, he created a strong Presidency to be the Prince, allowed each state to select two Senators to make an upper house where states would stand in for the nobility, and gave the public Representatives, wherein he vested the core legislative powers of the state. Of course, the direct election of Senators would later horribly break this system and ensure the total control of financial interests by giving far too much de jure power to the commons, but it was not reasonable to make a Constitution which cannot be amended and that was far after Madison’s time. Notably, Madison made the President both the Head of State and the Head of Government, a greater power than any constitutional monarch. The Head of State is the Prince, the great symbol of the state, while the Head of Government is responsible for the day-to-day running of the government. States rapidly modernized in Europe in the century after the American Revolution, and the trend was consistently towards a stronger Head of Government, such as the British Prime Minister or Prussian Chancellor, while the power of European monarchs persistently weakened.

The lack of kings in the Americas, outside of countries which never overthrew their European monarchs, likely has less to do with ideology or conceptions of liberty than with history and geography. The institution of monarchy has historically benefited greatly from “the Mists of Antiquity,” though as Paine explains at length the brutal fashion by which the Normans conquered England was well-known, and they lacked the ability to invent a nicer founding legend. Usually though, kings, and nobility generally, first took power violently in disorganized times with few written records, and then everyone forgot their past and they could tell a legend of a virtuous ancestor and say they were ordained by God, or at least in pursuit of some common good. In other instances, monarchs were greatly helped by it being what everyone else was doing, such as the period when Alexander’s successors and Agathocles the tyrant of Syracuse all declared themselves kings. In many more recent instances smaller newly independent states in Eastern Europe brought in random wealthy German “kinglets” to rule over them because in Europe having a king was the done thing [in the case of Greece they later overthrew the German they had chosen and brought in a Dane.] The most important instance of a non-noble crowning himself a monarch after the medieval era was Napoleon, and that was a unique situation fitting perfectly into its place in the cycle of constitutions, it did not last very long, and he only ever attained international recognition briefly from wars that he won [though amusingly, he retained the title of Emperor during his first exile.] Napoleon’s nephew, Napoleon III, did manage to hold on longer as Emperor, for 18 years, after he did a coup at the end of a Presidential term to which he was lawfully elected. The only serious attempt to bring a new monarch from Europe to rule over an independent American state was when this same Napoleon III attempted to make Maximilian Hapsburg the Emperor of Mexico following revolutionary Mexico’s refusal to pay the prior regime’s foreign debts, an affair which was disastrous for France and which ended with Maximilian not having his head attached to his neck.5

While there were strong republican tendencies among some American revolutionists, and Simon Bolivar was certainly a republican, as much as anything it just wasn’t reasonable to create a new nobility of the old style in a New World. While in the Spanish Americas various Spaniards gained enormous landholdings known as haciendas, they were based on a relatively modern conception of private property and not a feudal system of counts and dukes. Meanwhile, after the signing of the Constitution, it’s noteworthy they chose George Washington, the man most suited to be king, to be the first President. One wonders if he had been able to produce natural offspring [he was sterile from a childhood illness] if there would have been a stronger push for monarchy. One also wonder if with natural offspring he still would have been willing to leave office voluntarily after two terms, which he was under no obligation to do. However, it is more inspiring to not consider these factors and call him our Cincinattus, and anyhow founding legends are important.

In our time as a Republic, America has developed many proud Republican traditions, such as kneeling to no one and other types of formal egalitarianism, including finding kings ridiculous. However, being a Republic is not specifically the source of our liberty, particularly when one considers the rate at which we elect freedom-hating politicians at all levels. We have come to closely associate holding elections with having liberty, despite their obvious inability to safeguard our liberty. Regardless of mainstream views, it is not meant to be the act of voting which makes or keeps you free but the results of those elections. It is a path to liberty and one that has not been working in most countries for some time.

Part of my thesis here is that monarchy is more or less liberty-neutral, but it is now necessary to define “liberty.” Of course, it means more than just doing whatever you want. It is also more complex than “the non-aggression principle” or the basic bitch libertarian line of “don’t hurt people or take their stuff.” John Locke writes, in his Second Treatise on Government,

“So that, however it may be mistaken, the end of law is not to abolish or restraint, but to preserve and enlarge freedom. For in all the state of created beings capable of laws, where there is no law there is no freedom. For liberty is to be free from restraint and violence of others, which cannot be where there is no law. But freedom is not, as we are told, ‘a liberty for every man to do what he lists’, for who could be free when every other man’s humour might domineer over him?” [VI.58]

The reality of the situation is that liberty does require a secure and orderly society. If you must always protect your person from violence, you only have the liberty of a fugitive; if you must always protect your property with force, you only have the property rights of a bank robber who has taken hostages. Neither of these allow for a happy life or the development of society.

Liberty is a complex thing. Montesquieu writes, “There is no word that admits of more various significations, and has made a more varied impression on the human mind, than that of liberty” [I.XI.2]. He lists various meanings it has been assigned, including simply being governed by a native of your own country instead of a foreigner, regardless of what that government looks like. Commonly, people just use it to mean whatever form of government they like, and if you like how you are governed and feel you have nothing to complain about it is easy to feel as if your country has liberty, whether or not it is just or shared with all member of society. The definition of liberty Montesquieu ultimately gives is, “In governments, that is, in societies directed by laws, liberty can consist only in the power of doing what we ought to will, and in not being constrained to do what we ought not to will” [I.XI.3]. The phrasing is archaic, but what he means to say is that liberty consists in being allowed to do things we should do and not being forced to do things we shouldn’t do.6 This is a fair definition, and I think particularly important in a society where the government is always making us do stupid little things that are commonly harmful and also taxing us to do things that harm society, as opposed to using our taxes for some reasonable conception of the common good.7

This all explained, it brings us to the key point of “what are the current monarchies like for liberty and general quality of life?” More importantly, would they chop your head off for holding a “No Kings” protest?

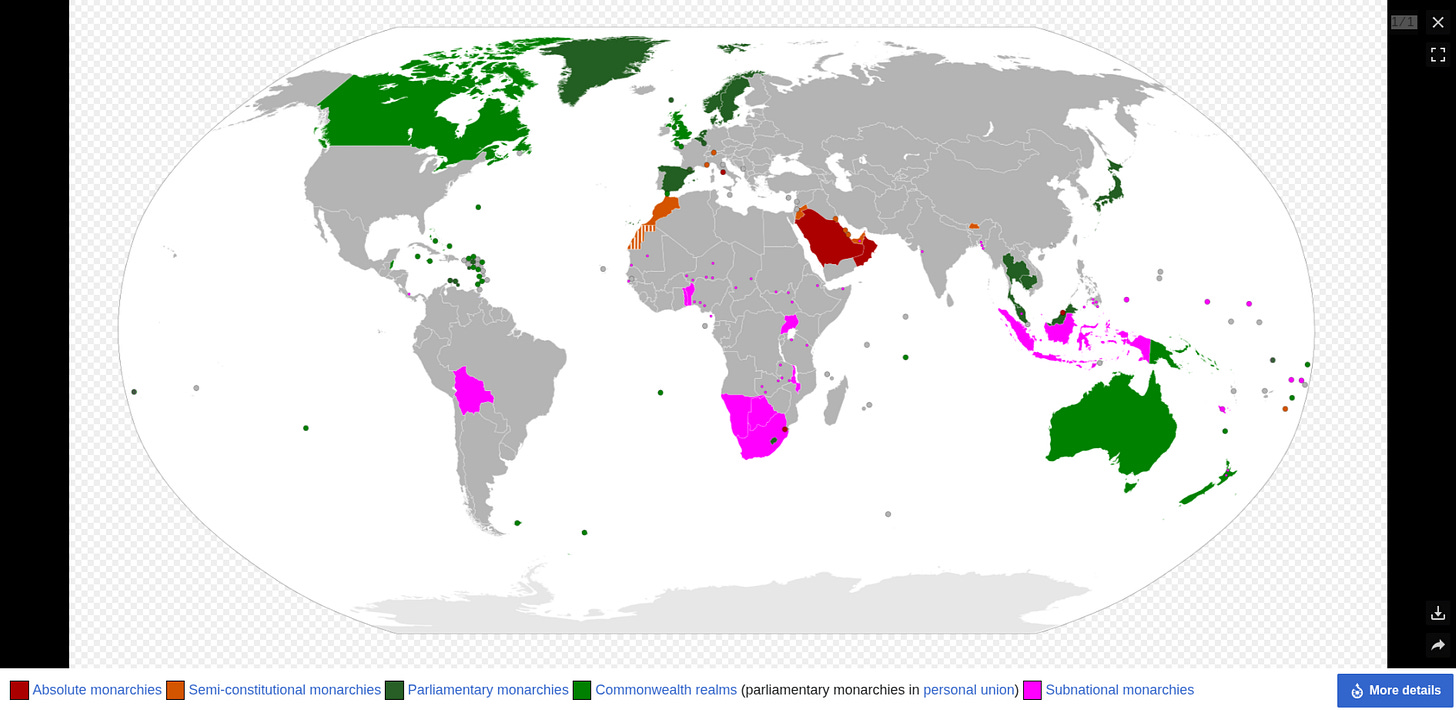

43 of the world’s countries are monarchies, and this is not exactly a map of hellhole countries though they vary. Overall, they are probably a bit nicer on average than the countries in their neighborhoods. It’s worth mentioning that most often a country which avoided its monarchy being overthrown was doing something right, or at least had oil, so it isn’t clear if monarchy is causal to making them nicer [though both Spain and Cambodia had restorations after brutal republican periods.] Regardless, among people who rate countries based on freedom, monarchies are top performers. There are problems with all of these ratings, but being about 1/4th of the world’s states, Freedom House lists monarchies as 7 of the 10 most free countries, CATO gives them 8 of the top 15, while the Global Expression Report gives 4 of the top 6 spots for freedom of expression to monarchies. In short, as well as being untrue in political theory, to the extent it can be objectively measured it is also objectively untrue that monarchy has any specific negative correlation with human liberty.

Anyway, when these people talk about heads being chopped off they are at best referencing the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, though I suspect they are more likely thinking of Agrabah in Disney’s Aladdin or even the guillotine in Revolutionary France. Regardless, in the legal system of our dear friend and close ally Saudi Arabia it is reasonable to say a person could be beheaded for holding a “No Kings” protest. KSA is currently the only country in the world where beheading is a legal form of execution. KSA is also the only major country in the world with a King as a Head of State that is among the world’s worst regimes for human rights [most of those are republics.] It’s worth mentioning that despite being an absolute monarchy, at this particular time the country is primarily ran by the Head of Government, the Crown Prince Muhammed bin Salman, though it is widely considered he will resume the practice of direct rule by the King upon ascending the throne. The only other absolute monarchy in the world that has a monarch known as King is Eswatini [formerly Swaziland,] a tiny shithole country in southern Africa where hanging is the only legal form of execution, though no one has been hanged in decades and there is only one person on death row; it is, however, plausible that security services would kill you in the street for protesting.

The other three kingdoms in the world where a king has any meaningful political power are Bhutan, Jordan, and Morocco. All of these are more or less reasonable regimes. Amusingly, in Morocco the King all but disappeared for a few years while running around with some MMA fighters who are basically the Moroccan version of the Tate Brothers, and it was fine despite that all government is supposed to go through the King. You probably wouldn’t want to take part in “No Kings” protests in any of these states, though I think within reason you could advocate for republican government if you didn’t insult the monarch. Morocco has had protests just this month, over economic issues, and they have lead to a fair amount of property destruction without, it seems, a particularly brutal police response. In these cases people generally are protesting the government, not the state.

The question of liberty in some of the smaller absolute monarchies is interesting. For example, Oman is known as a pleasant and relaxed country with a moderate government, but there are not political rights as we understand them and NGOs rank it poorly; there are elections in Oman but the legislature serves a purely advisory role and basically just does some of the work of government for the Sultan. You are not allowed to criticize the Sultan and would be prosecuted for it; one must admit the very name of “Sultan” conjures an image of oriental despotism, whereas “King” might just as well make you think of Elvis or a general cool person. The state of liberty in Oman is not bad based on Montesquieu’s definition.

The most interesting countries for our purposes are the Gulf Emirates. I will focus on the United Arab Emirates because I know the most about it by a wide margin, but what I say here also more or less applies to Qatar, Bahrain, and Kuwait. As said above, it is much more common that a prince [which is the equivalent of an emir] would have direct rule like people seem to think belongs to kings. Many people from across the world move to the UAE, both wealthy people who are tired of life in places like London workers of all skill levels. One sees arguments on the internet about where it is better to live, which inevitably bring up the lack of democracy and free speech in the Emirates. However, does one really have less liberty living in Dubai and paying no taxes and facing few regulations than one does in London or New York where you pay taxes out the ass to live in an environment where everything is chaotic and much doesn’t work? By the standard of letting you do what you should do and not making you do what you shouldn’t do, the UAE has a great deal of liberty despite being an absolute monarchy. However, at the same time, the UAE revoked citizenship and gave life prison sentences to people who merely signed a petition seeking democratization. This is insanely disproportionate and unjust, though you have to be a real gadfly to go around demanding democracy in a country with the material conditions of the UAE where any normal citizen who can read and write is most likely wealthy.

The majority of countries with kings, however, are parliamentary monarchies in Europe or Asia. The Nordic Monarchies, Denmark, Sweden, and Norway, are widely considered some of the nicest and best governed states in the world. Belgium hosts headquarters of some of the biggest liberal internationalist organizations. The Netherlands is an incredibly productive little country widely known for its socially liberal culture. Spain, which was mismanaged by a rigid monarchy for centuries, was a republic for around 40 years before the Monarchy was restored, and is now a pleasant country popular with tourists, though with perpetual high youth unemployment and less wealth than its northern neighbors. Smaller monarchies in Europe, such as the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, the Principality of Liechtenstein, and the Principality of Monaco are some of the wealthiest countries on Earth. Vatican City is an absolute monarchy, but is of course such a unique state as to not be useful for our purposes. In any of these countries besides the Vatican [which doesn’t have citizenry as such] you could hold republican protests in the streets and advocate for republican politicians or referendums on abolishing the monarchy, though there are generally rules against insulting monarchs, so some of the signs Americans carry about Donald Trump might get you a fine [in republican Germany you can be arrested for calling a politician fat on social media.] I do have to acknowledge that I think Democrats Abroad dropped the “No Kings” label because it didn’t make sense, not for fear of legal jeopardy, though I don’t know why they need to protest the American President in a foreign country at all. I suppose to show the Europeans that they’re “not like other girls.”

Regarding the Asian monarchies, the Japanese Imperial family was reduced greatly after WW2 [in the sense that more distant relatives were removed from it to cost the state less money.] The Emperor of Japan is still traditionally a deity of sorts, but criticizing him is considered free expression, though it upsets the public so much police may end up having to protect the person insulting the Emperor; frankly, any Japanese person who would publicly insult the Emperor probably has dangerous anti-social tendencies and perhaps should be removed from society.8 Regardless, the Emperor has no political power. In Thailand, the Royal Family is fabulously wealthy and it is a crime to insult them, a law which is regularly enforced. Though the Thai Royal Family has no public political power, there have been many coups in the country and it is generally believed they never happen without the King’s blessing. Malaysia is an elective monarchy where the royal families elect a federal monarch from among themselves to a 5 year term. The Cambodian Monarchy has no real power but was brought back to unify the country because the republican period was filled with unspeakable horrors.

About half of the worlds parliamentary monarchies are British Commonwealth states, many of which are tiny insignificant little territories. The state of liberty in Britain and their three main Anglo Commonwealths, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, has become appalling over the last few decades. They still do well on some global NGO ratings, but the natives are chased out of their neighborhoods by migrants, there are surveillance cameras everywhere, people are regularly arrested for social media posts, and more. Modern British governance typifies not letting you do what you should do but making you do what you shouldn’t: the modern British subject is prohibited from protecting his family from violent criminals but must support through his tax money the migrant invasion of his country [though now even Labour is at least pretending to be against mass migration.] Of course, the covid regimes were egregious in all of these states and Queen Elizabeth duly went along with and encouraged that scam. The problem has been the opposite of monarchical tyranny, it has been the complete lack of balance between the Monarch, the Lords, and the Commons in favor of ever increasing the power of the Commons.

For centuries the British Crown and nobility have let their power slide away for no good reason. British levelers have gone so crazy that they have removed the final hereditary Lords. For decades, it has been the case that the Monarch is meant to make no political statements nor even exercise their formal constitutional powers. Things such as dissolving Parliament, appointing and removing Prime Ministers, approving legislation, international treaties, and the powers of war and peace are all theoretically held by the Crown. None of these powers are exercised except at the request of the Commons. It was said after Elizabeth died that she had an extraordinary breadth of knowledge about international affairs and that Prime Ministers, who do meet with her regularly to give updates and “receive advice,” left kind of feeling like they needed to do what she said- due largely to her immense personal prestige- but it was to the point that instead of having “a power behind the throne” she was the quiet power behind PMs. I don’t think that the Crown should sully itself with day-to-day political affairs, but for example Keir Starmer has a 13% approval rating right now and it would be entirely reasonable to publicly state that Parliament will be dissolved if he doesn’t resign, though this would of course send shockwaves through the British political system. Similarly, the decision to pay Mauritius to take the British Indian Ocean Territory for no good reason is a situation where a Royal veto would have been appropriate. The only time Royal power has meaningfully been used in the modern era that I know of was the “Dismissal” crisis in Australia in 1975 when the Governor-General [the Queen’s stand-in] unilaterally dismissed the PM of Australia, which remains extremely controversial [when you go to this museum page a full page “land acknowledgement” thing comes up.]

If you’ve read this far please consider a paid subscription! This may surprise you but there isn’t big money in 10,000 word articles about what a king is!

The reality though is the British monarchy should have intervened in politics in favor of the liberty of its subjects decades ago. Not on partisan political matters, but big things, such as not filling the island with strangers, that the British aren’t criminals and don’t need to be surveilled at every step, or that it is insane to destroy energy production over global carbon goals [on this last one, Charles is as much of a carbon fanatic as Al Gore, so he clearly does personally approve.] In his capacity as the Head of the Church of England, King Charles should have spoken against Canada’s policy of euthanizing the poor, but instead, because he is a gay retard, he went there and gave a “land acknowledgement,” fundamentally apologizing for his family’s role in the creation of Canada. The whole thing is pathetic. Unless William makes clear he intends to “reign, not rule” differently, this particular Royal Family deserves to be thrown out because nothing could be worse than them.

Curiously, earlier this year there was a survey reported as if it was supposed to scare us about “extremism” among the younger generation in Britain. One data point was as follows, “Fifty-two per cent of Gen Z believe the UK would be a better place if a “strong leader was in charge who did not have to bother with parliament and elections”.” Yet nowhere in this whole thing meant to scare you about right wing extremism and dictators does it appear there was a single question about if anyone thinks the King should play a more active role in political life. Looking, I found one survey asking this which found the public roughly split about the monarchy’s involvement in domestic policy, except the question was asked in the nonsensical fashion of if “it is important to you,” not if you support or oppose it:

The reality this presents, to the extent one can learn anything from this question, is that the monarchy getting involved would at least be more popular than Parliament’s abysmal approval ratings and thus if they acted with some prudence the public would be sold on it. Of course, British “democracy” is now a system where everyone is unhappy all the time and nothing good ever happens but everyone tolerates it for no obvious reason but that famous British “stiff upper lip.” What Britain may need are more young men like this:

I suppose, after all this time, I should volunteer my own opinion. I am a basically fineist, which is a pragmatic non-ideological viewpoint that seeks to make society basically fine for the largest amount of people. I think monarchy is fine so long as it works, but it doesn’t make sense in the modern era to create monarchy where it has not existed previously. This is at least true in the case of the type of “God-ordained” hereditary monarchy. If you are going to have a primarily symbolic Head of State there is no reason to not make it a life appointment of some respected elder statesman who could be called King, though at that point the title is largely irrelevant. In general, I dislike the premise of solely ceremonial Heads of State. It is a stupid system which does not sufficiently separate powers and inevitably leads to an overpowered commons. This doesn’t mean that a President needs to be elected by the public or have the degree of power of the President of the United States or France, but if he is going to be the one to appoint Prime Ministers, call elections, and approve legislation, the Head of State should at least actually do those things instead of being a pointless vestigial functionary. Some Eastern European states do exist in this middle ground, where a fairly weak President does exercise those powers with discretion and it works fine. At the same time, you can’t replicate the general unifying power and sense of purpose that can be gained from a king. This is an entirely novel solution, but if the constitutional monarchs just actually used their own discretion in performing their constitutional duties, but stayed within the bounds laid down by law it would be a better system than the largely fake monarchies which exist now. I’m more interested in and sympathetic towards monarchy than any sort monarchist.

What should be clear at this point is Trump as President has very little in common with most kings or other monarchs as they have existed historically in the real world, besides being as rich as Croesus and his love for gilding things. Trump does like to act unilaterally and tends towards arbitrary decision making and micromanagement, which are not great traits in a political leader in general, though he often makes them work. Alternately, due to their lifetime positions and the desire to pass everything to their children, monarchs tend to have an incredible bias towards stability; only a demented monarch would actually use Trump’s technique of destabilizing everything around him in hopes of clenching a better deal. Nothing about this man’s rule is king-like besides the extent to which he has made himself the center of American political life, something which the Democrats caused as much as anyone [this was the good part of David’s broader point.]

On the other hand, though Trump is unlike any king that exists, he is perhaps like the king America would produce if it were to do so. Trump, one of the most famous Americans of the last 50 years, already in many ways represented America in a king-like fashion before he entered politics. I mean, think about it, the dude is a big brash burger-loving billionaire who has built towers all over the world and considers any wasted opportunity an outright loss. He hates immigrants unless they already have money, are building his railroad, or are beautiful exotic women sleeping with him. He poses with celebrities at prize fights. He stars in trash TV. He has ghostwriters come up with ridiculous books about how to be more like him. He can never say no to attention. He tweets out every deranged thought he has and thinks he’s been really clever. He once claimed in an interview like 30 years before he became President that he could be our best nuclear negotiator if you gave him 48 hours to study nuclear weapons. For better or, in many ways, for worse, Donald Trump was already the avatar of America before he became President, which is why all the liberals who always wanted us to be “more like Europe” without actually knowing anything about Europe hate him taking his rightful place as the chief American. The guy ran for President kind of already being our king, but only in the sense of a king as the ultimate representation of a nation’s culture and values. His political behavior is not at all king-like in either form or function.

Regardless, the only thing these protests have exposed is that Democrats are very old and that republicanism is so deeply ingrained in this country that Americans don’t even know what a king is, though we can agree on not wanting whatever we should happen to perceive a king to be.

Thank you for reading! The Wayward Rabbler is written by Brad Pearce. If you enjoyed this content please subscribe and share. My main articles are free but paid subscriptions help me a huge amount. I also have a tip jar at Ko-Fi. My Facebook page is The Wayward Rabbler. You can see my shitposting and serious commentary on Twitter @WaywardRabbler.

An interesting aside here that is not relevant to the broader point: in Rome most political leaders were assigned “lictors”, ceremonial guards who carried a fasces, in numbers based on the importance of their position. Alternately, the Tribunes were formally “sacrosanct” and the entire body of the plebeians was pledged to protect them and anyone of any rank who injured or interfered with a Tribune could be killed immediately without trial by any member of the public.

Assuming North Korea isn’t a secret paradise, being as everything we are told is a lie.

There is a quote I wasted a lot of time looking for, but never found, which notes that it is specifically an English trait to so closely associate liberty with taxation.

Strangely, the only major Founding Father who admitted to being an adherent of Machiavelli- who at that point had already been smeared for hundreds of years and “Machiavellian” in its current usage existed- was John Adams. Discourses on Livy is in fact the best text on how liberty is won and preserved and is explicitly anti-tyranny in many places.

Brazil was an independent monarchy for much of the 19th century, but the origin of this state of affairs was the Portuguese Royal Family fleeing the 1st Napoleon to their colony.

It is phrased strangely in the original French, “Dans un état, c’est-à-dire, dans une société ou il y a des loix, la liberté ne peut consister qu’à pouvoir faire ce que l’on doit vouloir, & à n’être point contraint de faire ce que l’on ne doit, pas vouloir.”

Grok gives this somewhat more helpful translation than the 1900 edition I have, “In a state, that is to say, in a society where there are laws, liberty can only consist in being able to do what one ought to want, and in not being constrained to do what one ought not to want.”

As another random aside, it is common to say that the Founding Fathers “lacked our conception of welfare” but in fact in this single most influential text on the Constitution he discusses the government housing the homeless and says the state, “Owes to every citizen a certain subsistence, a proper nourishment, convenient clothing, and a kind of life not incompatible with health” [II.XXXIII.29]. He doesn’t, however, specifically refer to it as “Welfare”.

In Inside Asia, written in the 1930’s, John Gunther tells a story of an American diplomat who wanted to show the Emperor of Japan a $1 watch and say, “I would like to see you copy this for cheaper.” It was impressed upon him that he couldn’t do that because all of the Emperor’s aides would kill themselves if they witnessed the Emperor being disrespected. As it turned out, it was a moot point because upon arrival in Japan he saw an imitation of the same watch for 30 cents.

Well I read all the way to the end of this very interesting essay expecting to see a discussion of how the Founding Fathers considered having a King, rather than a President. They did indeed consider this. After all, not a hundred years before, the mother country (England) had selected and appointed a monarch. This was entirely consistent with the traditions of constitutional liberty in the (then) new English mode.

The use of “Prince” by Machiavelli and others is due to the etymology of “princeps” which denotes the person who holds authority.